Stay Up to Date

Submit your email address to receive the latest industry and Aerospace America news.

ORLANDO, Fla. — NASA and its contractors are accustomed to designing spacecraft that can survive any number of harsh conditions on celestial bodies, from freezing temperatures to abrasive dust. Even so, the engineers and technicians developing the Dragonfly rotorcraft have faced particular challenges.

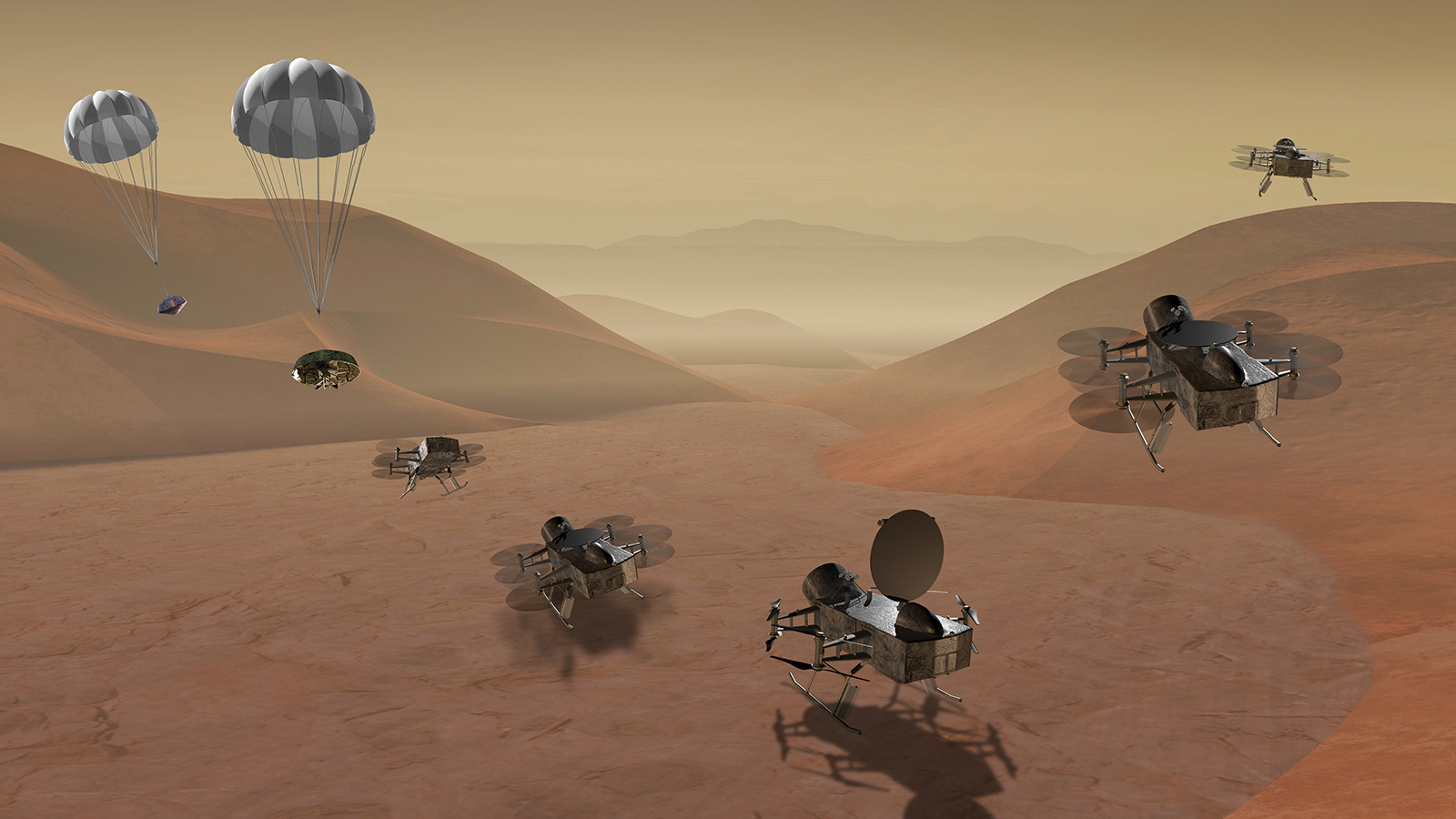

That’s because this octocopter, roughly the size of a Mini Cooper, is bound for Saturn’s moon Titan, an environment drastically different from any the agency has attempted to operate on. Ahead of the targeted 2028 launch, the Dragonfly mission team has made a number of changes to the spacecraft’s original design, including ones to address a lengthy anticipated descent through the moon’s thick atmosphere.

“We are into our flight hardware builds at this point and getting ready for our integration test of the lander” in February, when all components will be connected to test them as a complete system, said Elizabeth “Zibi” Turtle, lead investigator for Dragonfly at Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory, which is overseeing the $3.35 billion mission for NASA.

This month, leaders of Dragonfly team detailed the most significant obstacles they’ve had to address. These challenges are also the topic of multiple technical papers and talks this week at AIAA’s SciTech Forum in Orlando.

If the 2028 launch target holds, Dragonfly will arrive at Titan in 2034. Early on, engineers were aware of the challenges associated with entry, descent and landing — expected to span about 2 hours compared to the “7 minutes of terror” plummet experienced by the agency’s Mars spacecraft. However, they were surprised to discover Dragonfly faces a risk of overheating on the surface.

The initial concern was the lander getting too cold, with temperatures on Titan plunging to a low of minus 180 degrees Celsius. So plans called for equipping Dragonfly with a Multi-Mission Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generator, the same nuclear power source Mars Curiosity and Perseverance have. But simulations revealed that there was also a risk of the generator getting too toasty.

“Initially all the thinking was, we have to stay warm on the surface of Titan,” Turtle said. “There can be a slight breeze on Titan, and we had to design for that potential to stay warm with a breeze. But conversely — surprisingly enough — that means the lander could overheat if you have a completely calm day.”

Turtle said APL built two chambers that replicate Titan’s thermal environment. The smaller one can be chilled to Titan temperature and its extreme pressure “to test things like drilling water ice samples where ice is much harder than what we’re used to here on Earth,” she said, and the other, larger chamber “replicates the thermal, convective environment that we would have on Titan. So, we can really see how the outside of the lander will cool, how well the insulation is working and the thermal management system is working.”

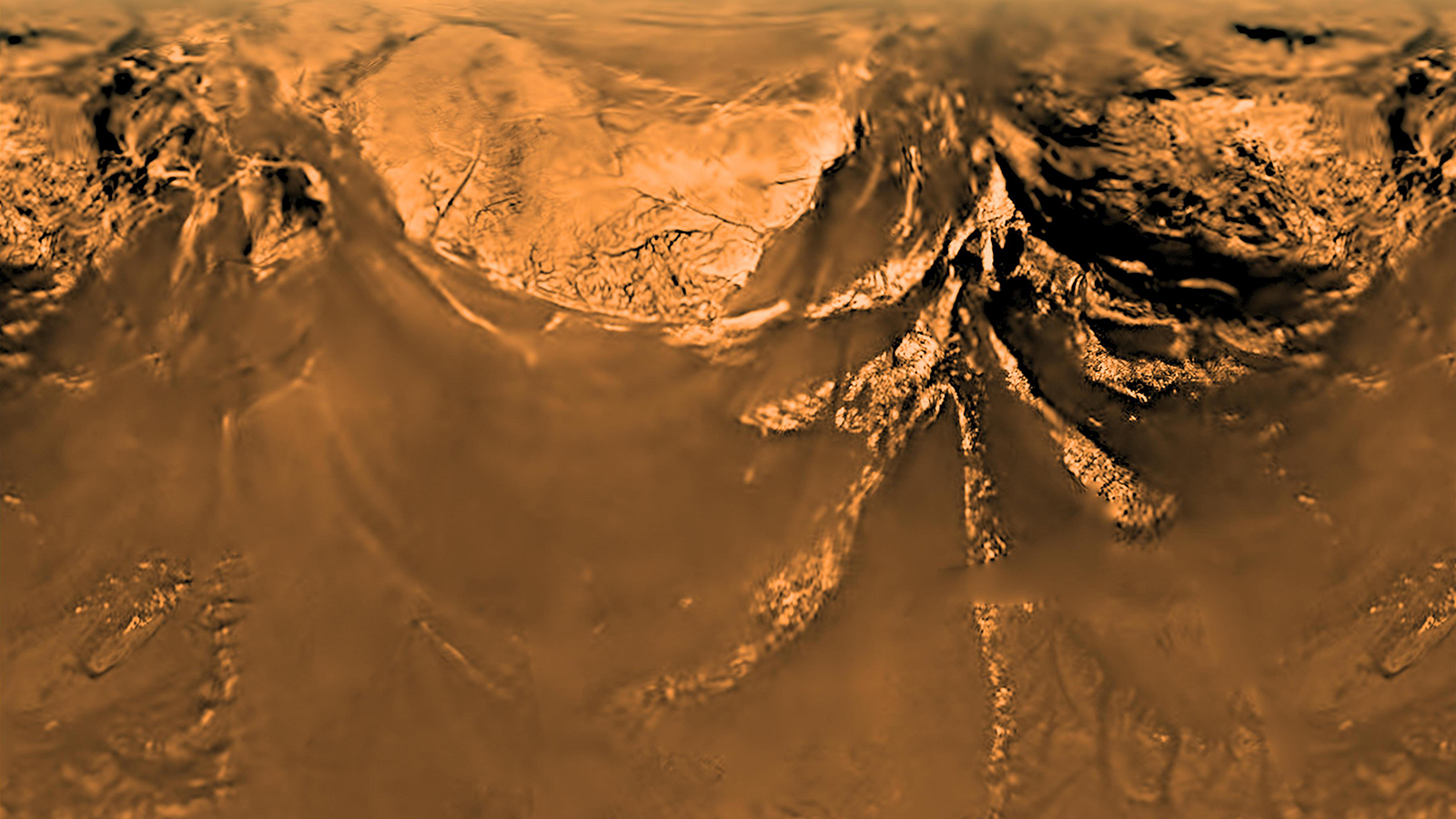

The moon’s dense atmosphere poses another challenge. Unlike Earth’s, Titan’s atmosphere changes slowly due to its long day — equivalent to about 16 Earth days — and long year, the equivalent of nearly 30 Earth years. That means, unlike planets like Mars that have wide-ranging temperatures, Titan’s temperature difference between day and night is minimal, Turtle said.

In the testing chambers at APL, the Dragonfly team was “able to demonstrate that the thermal system can react to” even those slight changes, with careful planning, Turtle said.

They also needed to “replicate the flow environment” of Titan’s thick air and how aerodynamics of the rotorcraft would behave there, she said. To accomplish that, they pumped R134 Freon into the Transonic Dynamics Tunnel at NASA’s Langley Research Center in Virginia and tested the rotors in that flow.

“Those are the kind of things that kind of come up as you get into the details of the design,” Turtle said. “We have developed conservative wind models and have demonstrated that Dragonfly can fly and land safely under Titan conditions.” These include the octocopter’s unique flight profile, which consists of series of “leapfrog” hops to survey the landscape.

And even though NASA expected the descent to pose a challenge, it still has had to make adaptations.

The descent is among the longest ever for an interplanetary probe, except for the 2005 descent of the European Space Agency’s Huygens probe to the surface of Titan. NASA must correct for large amplitude oscillations in the angle-of-attack or even tumbling of the aeroshell that Dragonfly will be enclosed in, which could result in mission failure. The agency also had to design the parachutes to slow Dragonfly’s entry inside an aeroshell with heat shield for up to 110 minutes.

After parachute testing to study the descent dynamics, NASA has “sized our drogue parachutes to provide sufficient stability to overcome” the long duration, Michael Wright, NASA’s Dragonfly Entry Descent and Landing lead, told me.

And some spin of the probe will be used to stabilize it at first, he added.

“We will use the spin rate to give us stability, and we expect to maintain some of that spin all the way till the end. So one of the things we need to do, before we release the lander, is end that spinning, and we’re actually using the rotors to do that as they start up,” Wright said.

Delay in reaching the landing zone and becoming fully operative could also pose a problem, but Wright is confident that Dragonfly’s design addresses that risk.

“Once the lander is released, it is only a matter of seconds before it is working to achieve stable flight, and the 100-plus minutes of time spent on the parachute prior to that moment are no longer relevant,” he said.

But that doesn’t mean it’ll be easy: Wright compared it to pushing an unoccupied bike to another person.

“You can push a bike 3 or 4 feet to your partner, and everything will be fine. If you want to push it 300 feet, you better make sure that bike is very carefully balanced,” he said.

Matching another world’s atmosphere exactly is impossible on Earth, but the testing data can all be analyzed and integrated to provide accurate models, he said. And such tests can also incorporate real data gained from Huygens.

“You’re never getting all the parameters right at the same time,” Wright said. “It tends to be a bit of a jigsaw puzzle to try to match what you can where you can, and then put all the pieces together into an integrated simulation of what will happen when we get there.”

About paul brinkmann

Paul covers advanced air mobility, space launches and more for our website and the quarterly magazine. Paul joined us in 2022 and is based near Kennedy Space Center in Florida. He previously covered aerospace for United Press International and the Orlando Sentinel.

Related Posts

Stay Up to Date

Submit your email address to receive the latest industry and Aerospace America news.