Stay Up to Date

Submit your email address to receive the latest industry and Aerospace America news.

Fire safety is a chief concern given lithium-ion batteries

With electric air taxis slated to be flying into and out of dozens or even hundreds of vertiports in metropolitan areas within a matter of years, something is bound to go wrong at one of them sooner or later.

That’s where the National Fire Protection Association’s Technical Committee on Helicopter Facilities comes in. In 2021, the group added vertiports, with their planned charging stations and storage facilities, to its historical role as the leading purveyor of design specifications for helipads in the United States. The latest version of the specification document, published in January, “Standard for Heliports and Vertiports, 2024,” refined those specifications to reflect FAA regulations that address new technologies, such as electric and hydrogen vehicles.

Safety for this coming mode of travel will require more than deconflicting flights and routes. “The hardest thing is not the geometry in the airspace. We can figure that out. I say it’s the fire code that’s the hardest nut to crack,” says Rex Alexander, an aviation consultant and the group’s chairman.

While air taxi companies express confidence over the safety of the lithium-ion batteries on their aircraft, it’s the job of Alexander’s group to make sure that a mistake or miscalculation doesn’t become calamity. A battery fire would be hot enough to melt aluminum decking on a rooftop vertiport, for instance, so safety officials must be mindful of batteries aboard the aircraft and also those in storage.

The group has set a deadline of January 2026 for public input to help guide the next edition of its specification, due to be published in 2028.

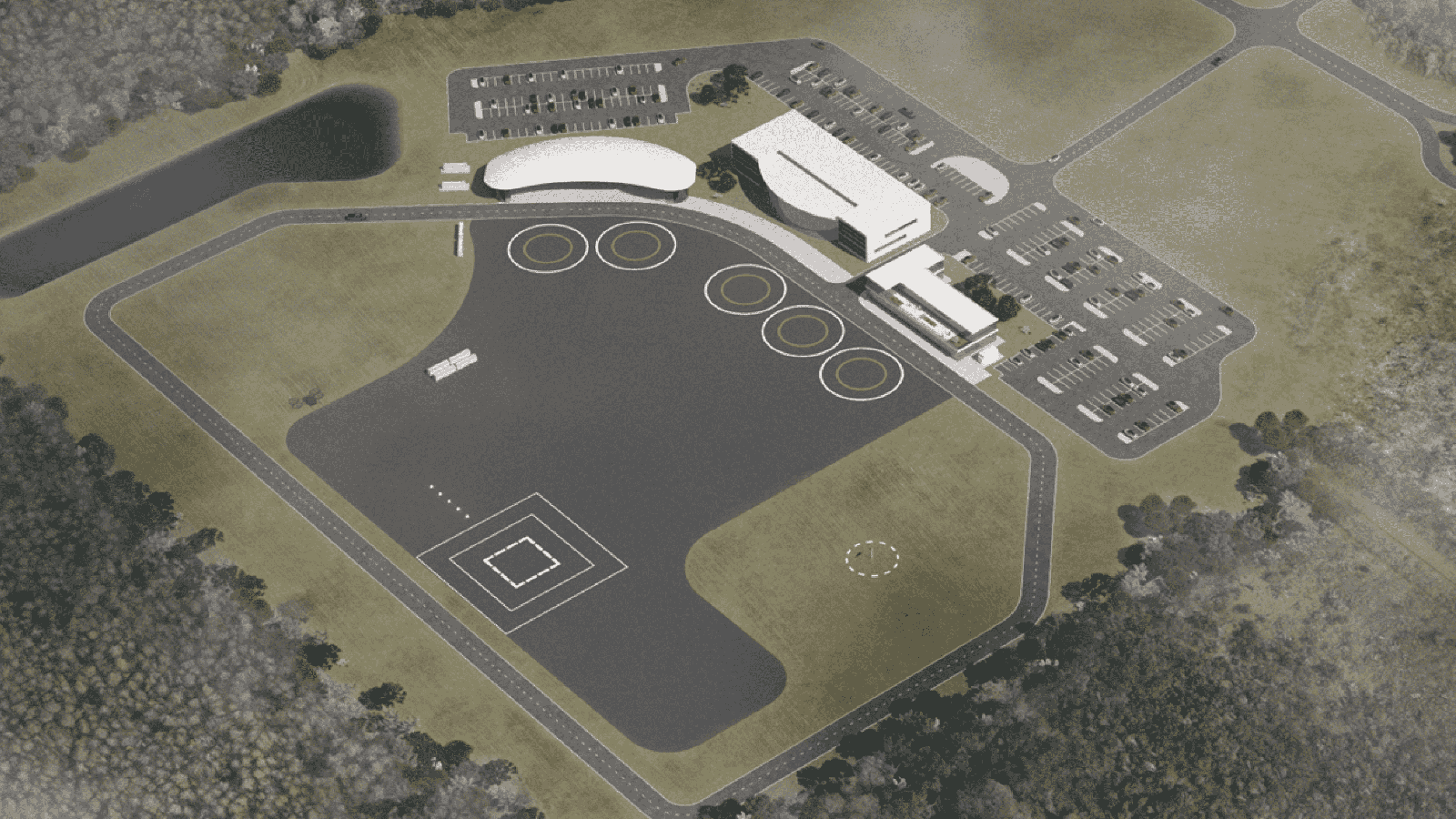

The 2024 standard adopts specifications set for electric car charging stations and provides an annex of guidances for those currently crafting plans for vertiports and also vertistops — places where electric air taxis might stop only to drop off passengers or cargo and where no charging or scheduled maintenance would occur. Those guidances could become specifications in 2028. Among them, for example, is an instruction that anyone constructing a vertiport intended to host electric aircraft may be required to present certain design and planning documents to rescue and firefighting personnel so they can be familiar with the facility and its layout in the event of a fire.

Among the concerns is that an aircraft could be on fire when it lands or that batteries stored at a vertiport could ignite. The standard describes the equipment that should be available to put out the fire and describes the training that people on hand would need.

Electric aircraft manufacturers are generally doing everything they can to minimize fire risk, but Alexander still sees possible dangers. As far as he knows, no one has yet measured the temperature that would be attained if an electric aircraft were to be engulfed. An electric car on fire burns at roughly 2,760 Celsius, while a gasoline-powered car burns around 800 C.

Get the latest news about advanced air mobility delivered to your inbox every two weeks.

That factor alone could require a city with many vertiports to consider improving its fire protection infrastructure, Alexander says. At the very least, vertiport personnel or air taxi pilots would need special training and firefighting equipment. Sprinkler systems capable of dousing a battery fire would also be required at each facility.

Some operators plan to set up vertiports or vertistops on rooftops, either by retrofitting existing helipads or by building entirely new facilities. Fire suppression requirements could mean that retrofitting an older building, while possible, would be an expensive proposition costing up to $1 million, Alexander says. However, placing a vertiport on the top floor of a modern parking garage could be easier and less expensive, he says, because such facilities tend to be underused during certain hours and overdesigned to have an ample supply of water to deal with automotive fires.

“I think it’s doable on the ground, but on a rooftop where you may have aluminum decking, the heat of a lithium battery fire would leave you with a lump of melted aluminum, and that’s a bad thing,” Alexander says.

Also, if vertiport developers expect to accept public funding to build, they will face expectations to allow other types of aircraft to land at their vertiports, he notes. That means vertiports could be expected to have charging stations, diesel or turbine fuel and, potentially, hydrogen. But Alexander says many existing heliport sites, such as those at hospitals, simply don’t have the real estate or funding to add additional landing spaces or equipment.

“They have helicopters today. They expect to have these electric aircraft tomorrow. And they’re already looking at small UAS [unmanned aerial systems] as well right now,” he says, so operating electric aircraft among those powered by conventional fuel could be difficult.

The 2024 edition of the standard states that battery-powered aircraft that intend to land at a vertiport but don’t comply with the standard adopted from existing electric car regulations “shall not be operated within three meters of fueling equipment or spills.”

One aspiring developer of vertiports, Clem Newton-Brown, CEO of Skyportz in the Melbourne, Australia, area, recently learned of the potential need for multiple modes of fire protection at such facilities.

“I can see this issue is going to get very complex if each vertiport is handling multiple aircraft types with multiple different types of fuel,” he said.

About paul brinkmann

Paul covers advanced air mobility, space launches and more for our website and the quarterly magazine. Paul joined us in 2022 and is based near Kennedy Space Center in Florida. He previously covered aerospace for United Press International and the Orlando Sentinel.

Related Posts

Stay Up to Date

Submit your email address to receive the latest industry and Aerospace America news.