Stay Up to Date

Submit your email address to receive the latest industry and Aerospace America news.

This story has been updated to correct the companies involved in a planned 2026 refueling demonstration.

Refueling satellites in geostationary orbit is likely possible in the coming years, according to a new NASA-backed study, possibly heralding a shift in satellite operations — provided there is sufficient demand.

The study was published today by COSMIC, or Consortium for Space Mobility and ISAM Capabilities, which NASA established in 2023. Members, some of which are from industry, investigated whether refueling satellites in GEO some 36,000 kilometers (22,000 miles) above Earth is viable from a technical and regulatory point of view.

“It’s something that can be done,” said co-author Dallas Bienhoff, a space systems architect at the space mining company OffWorld, headquartered in California. “We have everything we need technologically to do the job.”

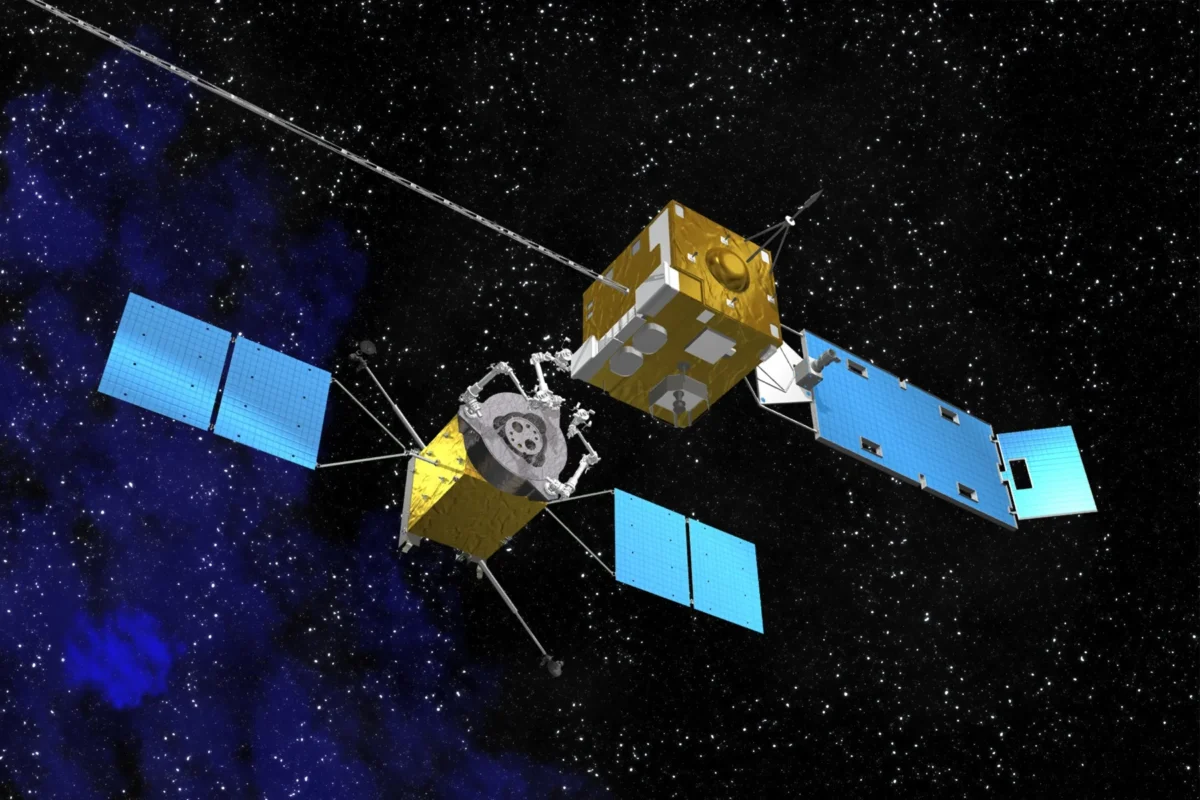

The concept of refueling satellites to prolong their lives has long been considered. In 2007, DARPA’s Orbital Express program demonstrated propellant transfer from a servicer spacecraft to a client in low-Earth orbit, while several companies have since demonstrated rendezvous and docking with their own servicers. Northrop Grumman’s MEV-1 and MEV-2 vehicles, for instance, docked with GEO satellites in 2020 and 2021 to provide stationkeeping to maintain their orbits.

But geostationary refueling would be a step further. “Nobody has pumped fuel into another system in GEO,” said Greg Richardson, the executive director of COSMIC, and previously a systems engineer who worked on Orbital Express.

This region, said Bienhoff, might be a great location to test refueling ahead of uses in other orbits. “In GEO, everything’s in the same [orbital] plane,” he said, “so it doesn’t take a lot of energy to move from one [satellite] to another.”

The study outlined how refueling depots, perhaps containing thousands of kilograms of propellant, could be placed in GEO. Smaller truck-like spacecraft would then take fuel from the depots to individual satellites, much like a delivery service. Several companies, including Colorado-based Orbit Fab and Denver-based Astroscale, are designing such technologies. In mid-2026, Astroscale plans to launch a satellite to GEO to refuel a U.S. Space Force satellite for the Tetra-5 demonstration mission. This servicer satellite is then to collect fuel from a depot launched by Orbit Fab to refuel another Space Force satellite.

While many of the necessary technologies for orbital refueling are already in development, the study noted they needed to be “demonstrated in a way that builds confidence in their reliability and effectiveness” in space.

Another barrier the study identified is the lack of a unified adapter that could allow fuel to be transferred from one depot to the multiple satellites operated by disparate entities.

“What we need to demonstrate is standardized interfaces,” said Richardson.

In September, the Space Force announced it would require its future satellites to have an interface that could allow refueling with fuel depots.

Additionally, Richardson said, while the actual process of rendezvous, docking and fuel transfer in GEO is mostly understood, the key is to deploy this at scale.

The major hurdles are largely logistical. “Many of the challenges we have are not necessarily technical, but more on the policy and demand side,” said Richardson. The questions include whether there is a big enough market for GEO depots to be financially viable, and who is responsible in the event a refueling sortie goes wrong.

“Who is liable?” he said. “We need to sort all that out.”

If that can be done, future GEO satellites could be able to operate much longer, sparing operators the need to move them to a graveyard orbit and launch new spacecraft.

“You’re talking 100, 200, 500% more life and more mission function,” said Richardson.

About Jonathan O'Callaghan

Jonathan is a London-based space and science journalist covering commercial spaceflight, space exploration and astrophysics. A regular contributor to Scientific American and New Scientist, his work has also appeared in Forbes, The New York Times and Wired.

Related Posts

Stay Up to Date

Submit your email address to receive the latest industry and Aerospace America news.