Esther Goddard: keeper of her husband’s legacy

Uneasy as Robert H. Goddard was with public attention, much of his research could have been lost after his death in 1945 from throat cancer — if not for his wife, Esther. She collected his papers, secured patents and worked with various institutions to establish exhibits and awards. Roger Launius and Jonathan Coopersmith explore Esther’s role as Goddard’s constant collaborator and champion.

Worcester, Massachusetts, was the center of Esther Christine Kisk Goddard’s life. She spent all her early years there and much of her later life, only journeying elsewhere between 1930 and 1945 when her husband, rocket pioneer Robert H. Goddard, relocated near Roswell, New Mexico, to pursue his experiments in the desert.

They met in 1919, while Esther was employed as a secretary at Clark University and attending Bates College. Although separated by a 20-year age gap, their shared intellectual curiosity and mutual respect laid the foundation for their marriage — a union that evolved into a lifelong collaboration that significantly shaped both their personal lives and Goddard’s path-breaking work in rocketry. After marrying in 1924, Esther and Robert Goddard moved to Maple Hill Farm near Worcester, Massachusetts. This was their home until they left for Roswell in 1929. She worked tirelessly to refurbish the house and make it comfortable. Naturally more outgoing than her husband, Esther also helped Robert become more socially engaged, remembering in her edited collection of Goddard’s papers: “The younger faculty people were casual and Bob liked them. He began to mix more easily.”

Esther became a dedicated assistant to her husband, photographing his launches; deciphering his notes — which only she could read — into easily digestible information; keeping his account books, sewing his payload parachutes for rocket launches; even putting out brush fires caused by rocket tests, and doing whatever else needed to be done. She described their life as “poised at the edge of achievement,” capturing well both the excitement and delicateness of their efforts together.

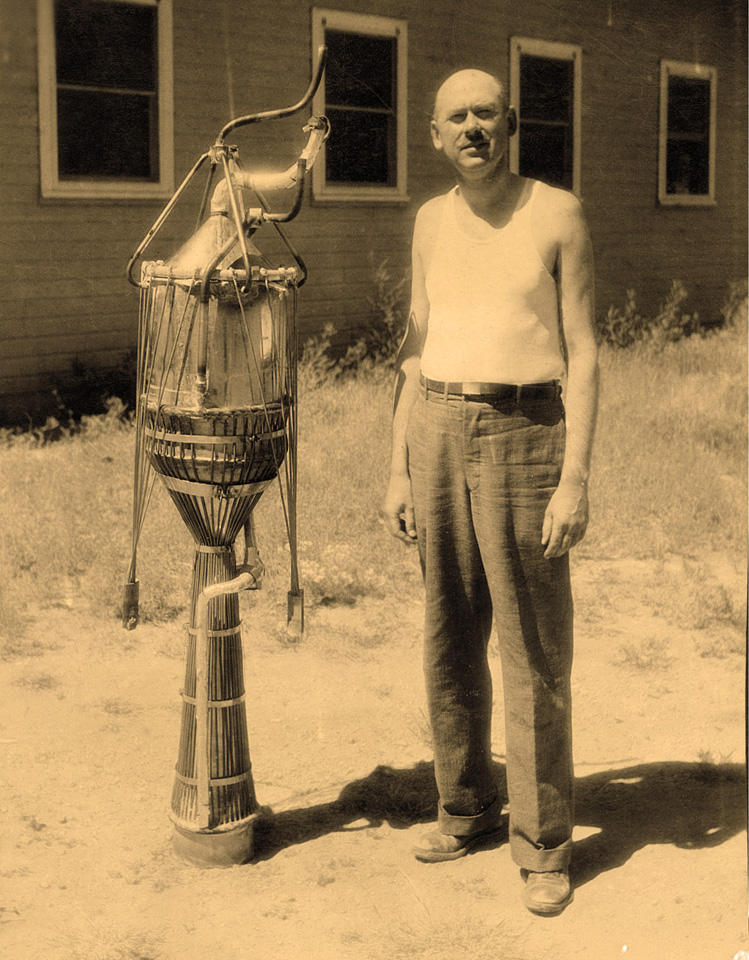

Esther Goddard in 1937 at the Goddards' home in Roswell, New Mexico. Clark University / The Goddard Rocket Researches: A Photographic Record

When they moved to the Mescalero Ranch near Roswell, which she considered “High Lonesome,” Esther not only continued her dedication to her husband’s research, but also served as his interface with the town. She founded a women’s club in Roswell as well as a book club that still exists. She expressed that this move provided “optimum surroundings” for her husband’s work away from the East Coast and offered relief from his nagging respiratory issues.

“During the fruitful years of full-time experimentation, financed by the Guggenheim family, he was an extremely happy man, doing what he most wanted to do, with adequate funds in optimum surroundings,” Esther recalled in her edited collection of Goddard’s papers.

At the same time, their New Mexico home was spartan; when Charles and Anne Morrow Lindbergh visited them in the latter 1930s, Esther remembered: “We had no beds and scarcely chairs to offer them … but we were not permitted to feel embarrassed.”

Soon after the start of World War II, the Goddards moved again, this time to Annapolis, Maryland, where Robert worked for the U.S. Navy on military rocketry until his death in 1945 from throat cancer. He was 62.

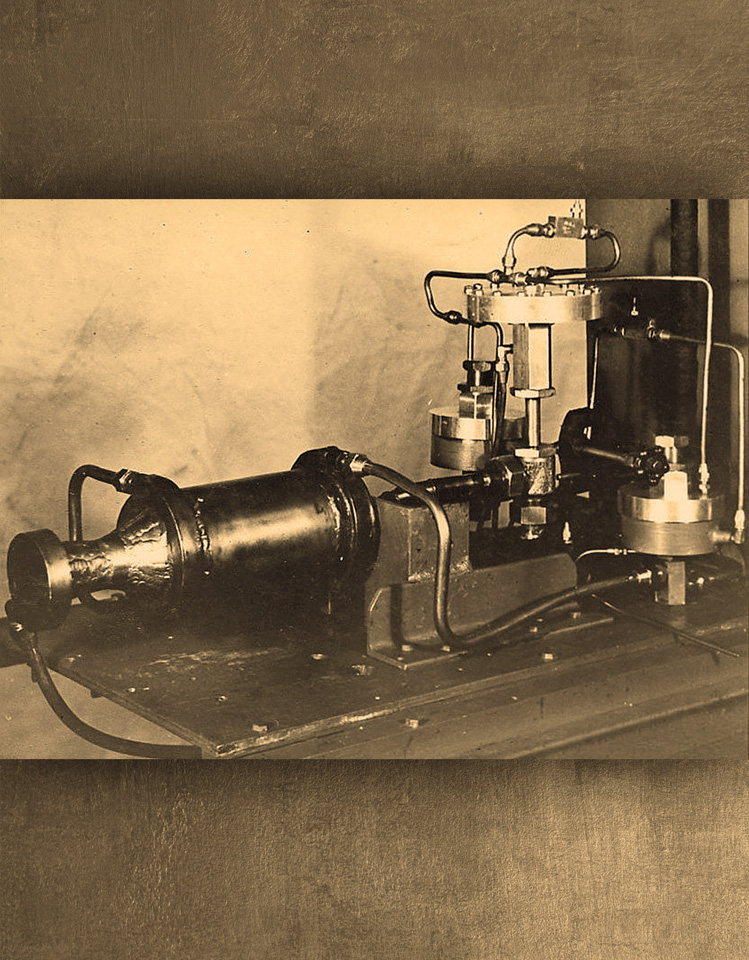

Goddard poses with a 12-inch-diameter rocket motor in 1932 in Roswell, New Mexico. Clark University / The Goddard Rocket Researches: A Photographic Record

Video: After his Guggenheim grant concluded, Goddard obtained a U.S. Navy contract to develop a liquid-propellant takeoff unit for aircraft. Tests began in New Mexico and in 1942 moved to Annapolis, Maryland. This was among his final research.

Thereafter, Esther earned a master’s degree from Clark University in 1951, served as a university trustee from 1964 to 1970 and received an honorary degree from the university in 1972. Like many widows — think Jessie Benton Frémont, who kept alive the legacy of her husband, John Charles Frémont — Esther devoted much of her final 20 years to promoting her husband’s work and ensuring he received credit for his rocketry innovations.

His patents became a major focus. Working with Worcester patent attorney Charles Hawley, she secured 131 of her husband’s 214 patents. She also immediately undertook efforts to secure payment for any damages due from patent infringement, submitting a complaint to the U.S. Army in 1957. Konrad K. Dannenberg, who had accompanied the rocket team of Wernher von Braun from Germany to the United States in 1945, received the complaint. Director of the Technical Liaison Group for the Army Ballistic Missile Agency (ABMA), in Huntsville, Alabama, Dannenberg passed the correspondence on with a DD95 routing memorandum containing a handwritten note: “Forwarded to you as a matter pertaining principally to your Section. Sympathetically!” “Sympathetically” was underlined five times. Dannenberg, or some other ABMA official, certainly appeared understanding of Esther’s position on the matter.

Responsibility for the investigation landed on the desk of Dave Christensen, a young engineer involved in the Redstone and Jupiter missile development programs who would later go on to work on the Saturn I H-1 engine. He found that infringement of Goddard’s patents had indeed taken place and recommended paying Esther a settlement. By the time this happened, the rocket program at ABMA had moved from the Army to NASA, and in 1960 the space agency settled the case with a $1 million payout to Esther.

Among Goddard’s final work was the development of a variable-thrust motor that became the basis for the engine that powered the Bell X-2 supersonic research plane. This 1942 picture shows the test apparatus for a variable thrust pump unit. Clark University / The Goddard Rocket Researches: A Photographic Record

The case was a landmark one in intellectual property; it also allowed Esther to secure not only resources for the future but also official recognition that her husband’s innovations had made America’s spaceflight achievements possible. While the case was being settled, NASA named its new space laboratory outside of Washington, D.C., the Goddard Space Flight Center, to honor Goddard’s legacy.

Perhaps even more significantly, Esther meticulously sorted and organized her husband’s papers, donating them to Clark University, where they found an honored place in the Goddard Library after its opening in 1969. Focused on ensuring her husband’s recognition, she used the funds from the patent infringement settlement for publications, museum donations and educational outreach.

She edited and published her husband’s “Rocket Development: Liquid Fuel Rocket Research, 1929-1941” in 1961. She also collaborated with G. Edward Pendray, a founder of the American Interplanetary Society and a passionate space exploration advocate, to produce the three-volume set, “The Papers of Robert H. Goddard,” published in 1970. A comprehensive account of his life and work, this 1,700-page set remains an indispensable source on Goddard’s career as America’s foremost early rocket developer.

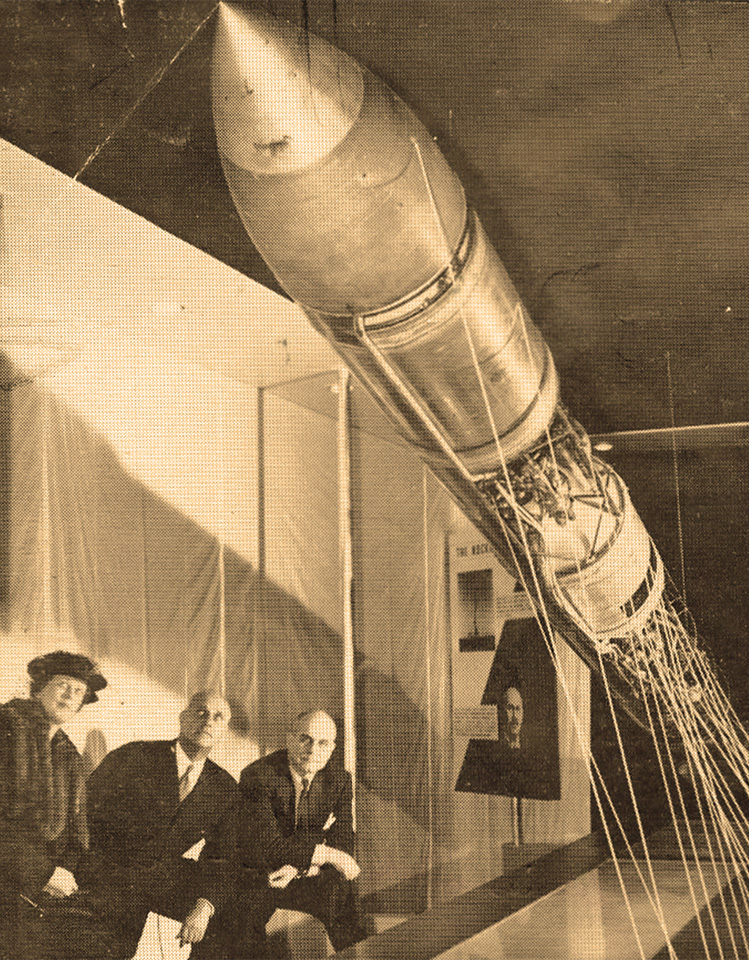

Esther Goddard (far left) with Harry Guggenheim and Jimmy Doolittle at the 1948 opening of the Goddard Rocket Exhibit at the American Museum of Natural History. Clark University / The Goddard Rocket Researches: A Photographic Record

Esther wrote in her introduction to the book, “This work is the result of many years of effort to preserve and present the record of a man whose vision and persistence opened the way to space flight.”

In undertaking this project, which took more than a decade, Esther commented: “It has been a labor of love, and at times a lonely one. But I felt it was my duty to make sure that his voice would not be lost.”

Esther tirelessly labored to ensure that museums around the country celebrated Robert’s legacy. In 1965, she donated his 1916 Magnesium Powder Experiment Box to the Smithsonian. It remains the oldest space-oriented artifact in the national collection. She also contributed materials to the Roswell Museum, helping establish the Robert H. Goddard wing in 1969. In every instance, Esther ensured that her husband received his due as a foundational figure in space engineering.

Without question, Esther Christine Kisk Goddard was not merely Robert Goddard’s wife — she was also his indispensable partner, collaborator and steward of his legacy. While Esther passed away in 1982, her impact endures through her efforts to document and publicize her husband’s legacy.

Roger Launius is a former chief historian of NASA and associate director for collections and curatorial affairs at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C.

Jonathan Coopersmith is an historian of technology and former professor at Texas A&M University in College Station who has written about 20th century space commercialization.