Stay Up to Date

Submit your email address to receive the latest industry and Aerospace America news.

Thousands of commercial drones could someday whisk packages to our doorsteps, spot dangerous pipeline leaks, and inspect bridges and crops. A revolution of that scale would require accepting that drones must fly out of visual range of their operators. That can’t happen unless the FAA approves a scheme for safely managing thousands of drone flights. David Hughes, formerly an FAA writer and editor, gauges progress on UTM, or unmanned aircraft system traffic management.

Andy Thurling, a former U.S. Air Force test pilot, had an epiphany back in 2012 while analyzing the safety case his employer at the time would need to make to the FAA to win permission to fly 7-kilogram drones beyond visual range for pipeline inspections and other applications. He felt confident that the risk of colliding with passenger planes could be addressed through geofencing, in which software and GPS keep the drones from flying into prohibited airspace, such as near airports. He realized the bigger problem would be proving to the FAA that the drones would not collide with other drones, or with conventionally piloted crop-dusting planes or helicopters that also fly at low altitudes.

As it turned out, NASA had realized much the same thing. Looking into matters, Thurling talked with Parimal Kopardekar of NASA’s Ames Research Center in California. Kopardekar was about to start an ambitious multiyear research initiative in collaboration with the FAA to define the best sensors, software and strategy for managing commercial drone flights beyond line of sight.

“As long as you have more than one vehicle going, you need some sort of management system,” says Kopardekar, the principal investigator for NASA’s UAS Traffic Management initiative, or UTM.

Package delivery to consumers alone could put thousands or hundreds of thousands of drones in the air over the U.S., compared to today’s count of about 5,000 conventionally piloted aircraft in the air at any one time.

After seven years, some in the commercial drone field are beginning to get anxious that all the prerequisites for making UTM a reality are not yet in place. FAA has established an overall concept of operations, but not the performance requirements for the drones that would operate within that UTM.

“The friction will come when the drone industry is ready to go and the government is not,” says air traffic management consultant Charlie Keegan, who once led air traffic modernization at the FAA and is a former chairman of the Air Traffic Control Association.

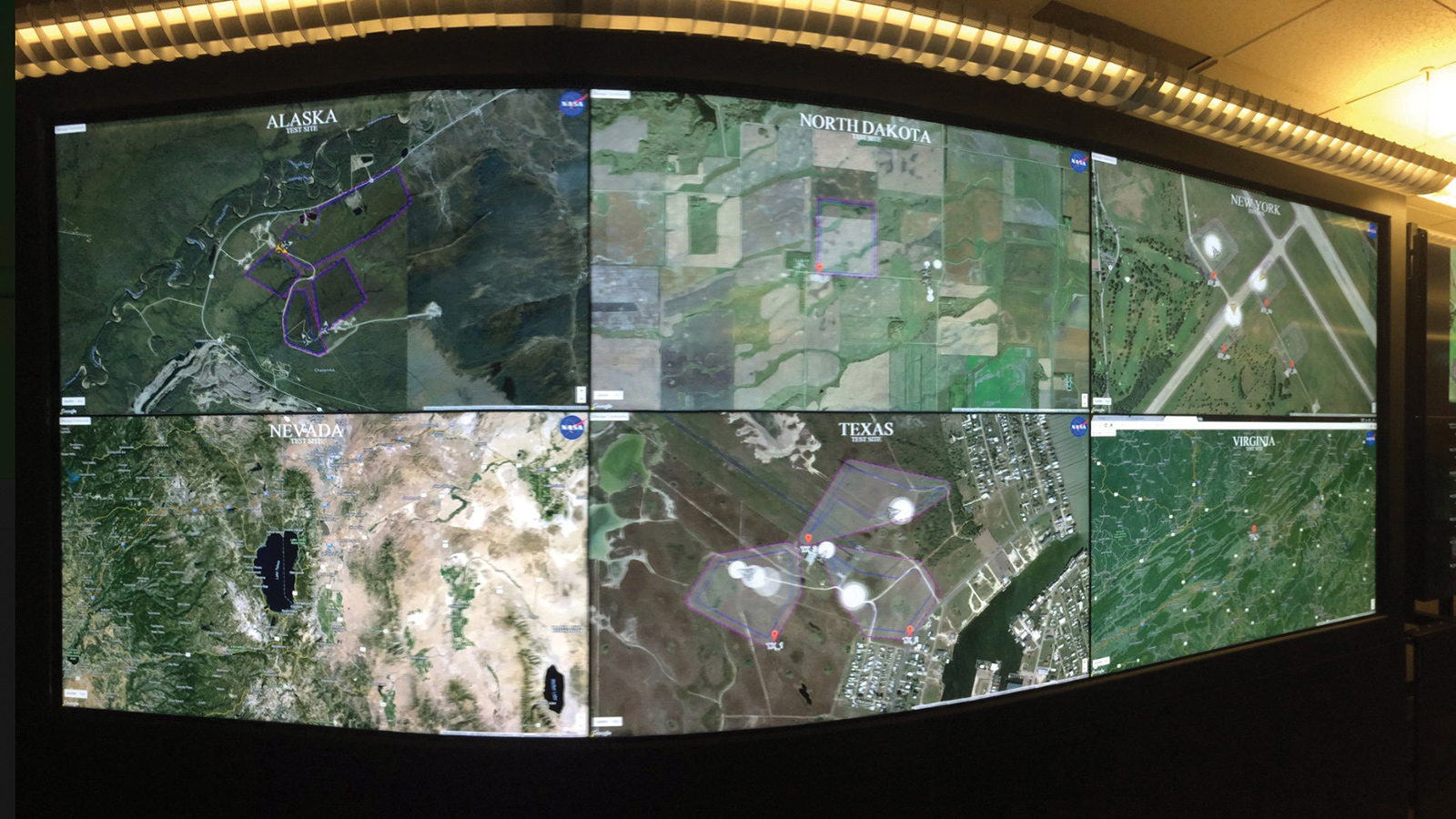

Since 2012, Kopardekar’s team has spent an average of $18 million a year on UTM and conducted three field tests, and is about to start a fourth. At least one test involves 20 drones in the air plus simulated drones. The focus is on operations beyond the view of operators in airspace below 400 feet. The FAA last May adapted what it learned through the NASA project and released a detailed concept of operations for UTM, which is part of what’s needed to make UTM a reality.

The current national airspace system will not be able to handle the growth and air traffic demand that is coming, says consultant John Walker, a former senior official at the FAA who is involved with international regulatory bodies working on UTM.

He thinks emerging aerospace technologies in UTM and other areas of UAS activity such as international flights by larger drones under instrument flight rules will tip the scales to produce the largest changes in civil aviation since the introduction of radar, the jet engine or GPS. And UTM alone is already forcing the international community to establish new flight rules.

For UTM to happen, the system must be safe enough to be verified and approved by the FAA. Only then can commercial operations begin on a large scale and with money-making efficiency. The FAA says in an email the agency is working to achieve this objective but that it must still roll out the rules, policies and standards needed to make it happen. FAA did not offer a timeline.

Today, the FAA permits commercial drone flights only if operators keep their drones in sight over sparsely populated areas, or if they receive waivers. The agency has granted about 2,400 of these waivers so far. The commercial market is already sizeable, with 316,000 of the 1.3 million drones registered in the U.S. listed for commercial use, said Transportation Secretary Elaine Chao to an audience at the U.S. Chamber of Commerce’s Aviation Summit in March.

It is one thing to have a single drone inspect a bridge as a pilot on the ground watches and another thing to have multiple drones looking at lots of bridges beyond visual line of sight, says Thurling, who is now chief of technology at the not-for-profit Northeast UAS Airspace Integration Research Alliance in upstate New York. His group runs one of the FAA drone test sites chosen by the agency in 2013 to help integrate drones into the national airspace system.

The FAA is working with NASA to define the requirements for data exchange, communications and navigation. The FAA through a pilot program is demonstrating a prototype of the data exchange approach. “The rollout of UTM will be incremental in nature, and will be done through increasingly complex capabilities, rules, policies and standards,” the FAA statement said.

How UTM might work

Because of the anticipated volume of flights, UTM will be different from management of conventional flights, in which a pilot talks over a radio to an air traffic controller and exchanges data. Commercial drones are going to need a good dose of automation to deconflict themselves and stay clear of other aircraft, and one operator might control multiple drones.

Kopardekar explains that in the UTM concept multiple unmanned aircraft would inform each other about their “intents,” meaning their flight plans or intended areas of operation. The plans are made from the start to avoid other drones as much as possible and everyone takes some responsibility for separation, he says.

Third parties called UAS service suppliers are expected to coordinate, execute and manage small drone operations in part by sharing information with each other. The FAA sets the rules of the road and provides oversight, but air traffic controllers won’t be conducting UTM.

The traditional air traffic control human-in-the-loop scheme won’t work for thousands of drones flying below 400 feet. “Do you think Amazon is going to make any money delivering packages if they have to have one pilot for every drone? That isn’t going to happen,” says Thurling. “There is no human controller managing individual aircraft in the UTM construct and its counterpart above 60,000 feet [where long-endurance commercial drones may operate]. A team of humans will monitor a large area.”

Amit Ganjoo, chief executive officer of ANRA Technologies, a startup that makes UTM software, underscores this point. “Right now in UTM testing there is always at some point a human in the loop, but in the long term most of it is going to be automated and cellphone-driven.”

However, an FAA official says when a drone operates where the FAA provides separation of aircraft, it will have to comply with all air traffic rules in that airspace.

Advice from the industry

Some see opportunities for speeding up progress.

“We haven’t taken the opportunity to step back and consolidate what we have learned into performance requirements. That is something the community has fallen down on,” says Thurling.

Groups that have a stake in the use of low-altitude airspace are asking some hard questions. The Academy of Model Aeronautics, for example, wants to make sure that its members who have been flying model aircraft with an excellent safety record for 80 years are not penalized by unnecessary new requirements. “We want to caution the FAA and industry that they can’t push recreation out of the way to make way for new commercial operators,” says Tyler Dobbs, government affairs director for the group.

Private-sector money may turn out to be the driving force that makes UTM happen. Venture capitalists are funding some of the proposed business models for drones — such as package delivery — that will need to have a UTM system in place. These private companies aren’t waiting on government research or contracts for new technology to trickle down, according to Keegan. “They are using private equity to rapidly build the necessary elements for drone support systems (akin to UTM), collecting information and using it for safer flights with very little oversight from the government,” he said in an email.

There is a strategic shortcoming that could stand in the way of getting UTM ready to go, cautions consultant Neil Planzer, who once led Boeing’s air traffic management organization and has held senior positions at the FAA and the U.S. Air Force.

The problem is that drone operators and governments around the world are testing the technology needed for safe operations to then create an overall strategy.

“This is a backward way of doing it,” he says.

He thinks what is needed is a top-down UTM strategy to produce a system that can be certified as safe. “I would have a blue-ribbon group established by the United States to look at how we are going to integrate unmanned aircraft in the system, not from a detailed technical but from a strategic standpoint,” he says. “What are the policies, procedures and requirements for safety that we need to consider and then move down from the strategy to the tactical.” He would give such a high-level group just six or nine months to complete its work.

As an example of the type of group he has in mind, he cites the National Civil Aviation Review Commission led by former Transportation Secretary Norman Mineta. That commission was charged with addressing traffic congestion and safety. The commission’s 1997 report prompted the creation of the FAA’s performance-based Air Traffic Organization and other changes. Planzer thinks a UTM panel needs to be led by someone of Mineta’s stature.

Planzer also suggests a European group might do its own analysis and then the results of the two efforts could guide the International Civil Aviation Organization, which recommends practices to its 180 member nations. Walker says Japan is already doing something along these lines.

Europe has similar concerns about the overall strategy. Mike Lissone, who is the drone manager for Eurocontrol, says nations in Europe need to analyze airspace and set requirements for new entrants. “What is mostly happening now is the other way around as they allow drones to fly and find out later what is actually necessary to operate them safely. That is not the way we ordinarily do things in aviation.” Europe’s UTM effort is called U-Space, and it is focused initially on altitude below 500 feet, but it is not restricted to low altitudes.

International standards

Thurling and others want the global drone community to develop standards for drone performance that specify the requirements needed for a safe system.

Today, there are at least a half dozen standards and advisory organizations in the United States, Europe and the Asia-Pacific region addressing UTM standardization. The FAA engages with all of them. Safety regulators from 59 nations, including the FAA, are also working together informally on the Joint Authorities for Rulemaking on Unmanned Systems. The group has published a risk assessment methodology to scope out the safety of UTM operations. But when it comes down to implementing a UTM system in the U.S., only the FAA can mandate what has to happen to create a safe system.

Walker says the Global UTM Association, an international consortium of drone and UTM companies, air navigation service providers and other groups that want to influence UTM developments, is trying to corral all of these efforts around the world. The association is trying to make sure standards and advisory bodies are not duplicating efforts or publishing guidelines that disagree with each other so that everything is aligned, Walker adds. But it won’t be easy.

Ganjoo says everything has to be standardized from air vehicle performance to the technical specification of how data will be exchanged between systems. And he worries there will be some level of fragmentation in the next few years as various nations try to own a piece of the puzzle as new things bubble up and go live. Then after the fact, all of the various schemes will have to interoperate.

Whether the international paths will converge remains an open question, as does the timeline for finalizing a UTM system in the U.S. And with the cycle of technology development in the computer age serving up new things in a year and a half while government regulatory cycles around the world run at more like five years, there is probably some conflict on the horizon between commercial drone innovators and government approvers.

“The friction will come when the drone industry is ready to go and the government is not.”

Charlie Keegan, air traffic management consultant

About David Hughes

Dave has been an aviation writer and editor for 10 years in the avionics industry, 20 years at Aviation Week magazine and 10 years at the FAA. He was a C-5 Galaxy pilot in the U.S. Air Force Reserve.

Related Posts

Stay Up to Date

Submit your email address to receive the latest industry and Aerospace America news.