Stay Up to Date

Submit your email address to receive the latest industry and Aerospace America news.

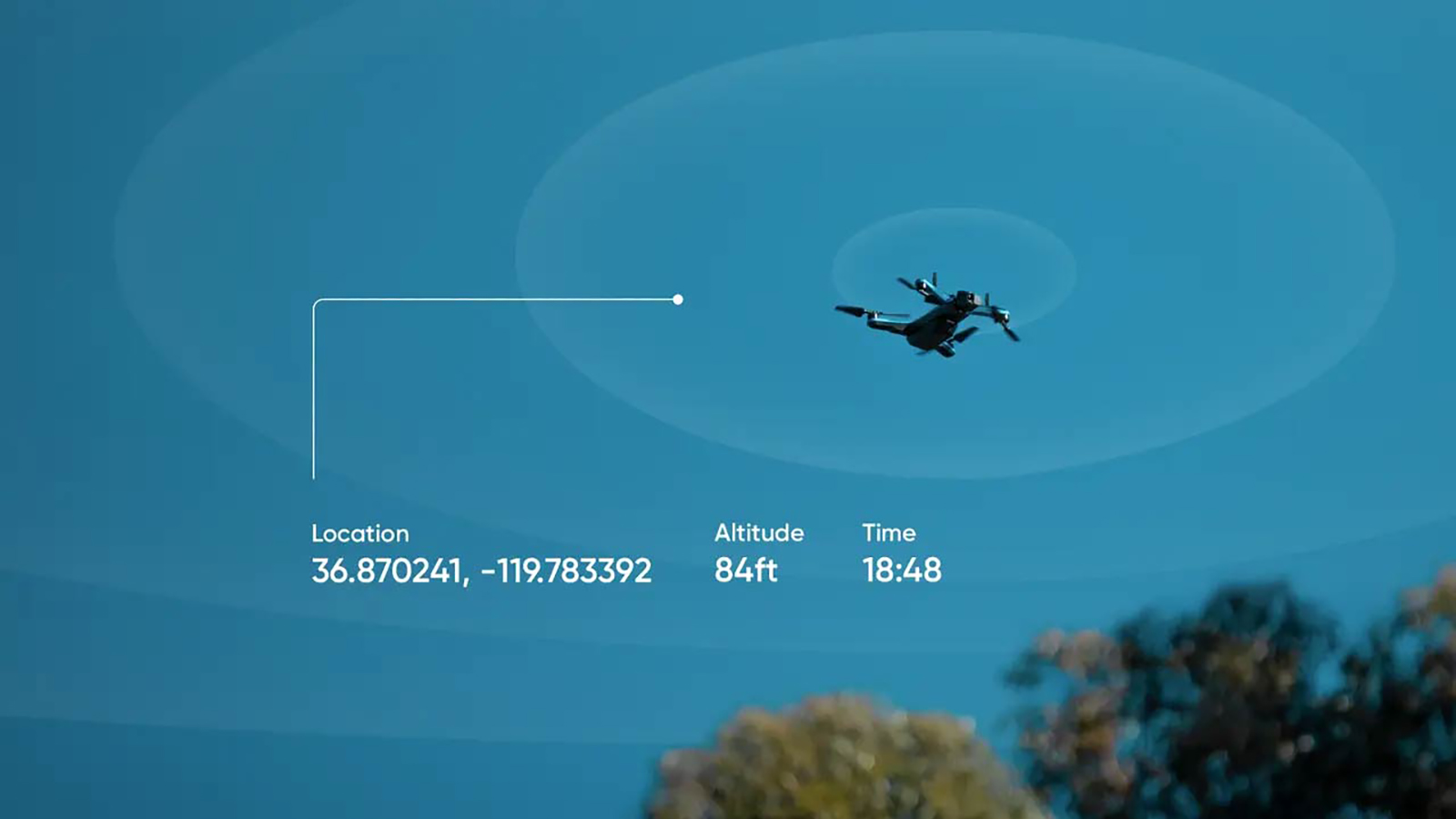

Starting Sept. 16, commercial and hobby drones in U.S. airspace must fly with digital ‘license plates’

This story has been updated to clarify that the rule does not apply to drones weighing 0.55 pounds (249 grams) or less.

The Remote Identification technology that all but the tiniest drones must have aboard in the United States starting next month is primarily meant to aid police and citizens who want to know who owns a drone flying nearby that might be maneuvering unsafely. Technologists, however, see the approach as the potential precursor to a tool for managing the long-predicted explosion of drone traffic for package delivery, infrastructure monitoring and other applications.

The requirement stems from an FAA rule finalized in April 2021, which set a Sept. 16, 2023, deadline for when each drone must begin transmitting its identity, point of origin, current position and heading. The rule applies to all registered drones, meaning those greater than 0.55 pounds (249 grams), whether they are flown by hobbyists or for business purposes. Anyone with a Remote ID-compatible app installed on a smartphone or tablet could receive the information directly from the aircraft, much like how Wi-Fi or Bluetooth works. The information would not be routed through a cell tower or sent via protected frequencies like those carrying transmissions between FAA air traffic control towers and passenger aircraft.

“It is not a strategic deconfliction service; it’s simply a license plate in the sky,” says Scott Shtofman, senior manager of government affairs at the Association for Uncrewed Vehicle Systems International. “FAA started out by trying to make Remote ID a networked service, but that didn’t happen,” though someday it could, he adds.

For now, airline pilots, for instance, would still need to avoid drones by relying on radar detections or by receiving the Automatic Dependent Surveillance-Broadcast radio transmissions from newer drones and prefiled flight plans, says Rob Knochenhauer, director of regulatory affairs at Florida-based drone manufacturer Censys Technologies Corp. Today, small drones defined as under 55 pounds (24.9 kilograms) are not required to be equipped with ADS-B.

The industry has been preparing for the Sept. 16 deadline. For example, Censys put a freeze on sales and manufacturing of drones for six months in 2022 to engineer a redesign of flight control, navigation and communication software to meet FAA’s Remote ID requirements, Knochenhauer says. FAA required manufacturers to produce Remote ID-capable drones by December 2022, in anticipation of the upcoming September deadline for drone operators.

“We’re not sure how much of a problem this transition to Remote ID will prove to be. There’s excitement but also consternation at how complicated the rulemaking process was,” Knochenhauer says.

At Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University in Florida, Ryan Wallace, an associate professor who coordinates the university’s drone science program, is about to embark on an FAA-funded research project to assess the implementation of the Remote ID rule. He tells me he’s planning to deploy sensors at multiple U.S. locations to collect and relay Remote ID transmissions from drones to a database he will maintain.

“We’re going to evaluate the effectiveness of Remote ID systems, activity levels in certain locations near airports and whether that activity presents any particular hazard to the National Airspace System and so on,” Wallace says.

Owners of older drones must add a Remote ID transmitter and supporting equipment, unless they only plan to fly within an airfield designated for radio-controlled hobby aircraft, known as an FAA-Recognized Identification Area, or FRIA. But Wallace says he is concerned that many people — such as hobbyists or real estate agents — who haven’t used their drones in a while may not be aware of the requirements.

Wallace says Remote ID is a first step toward more thorough monitoring of drones in flight. Currently, because Remote ID signals are not picked up by cell towers and networked in any way, such signals do not contribute to aggregate maps or databases showing aircraft locations, he says. But FAA and NASA have researched ways to use Remote ID data to create an unmanned aerial system (UAS) traffic management, or UTM, network.

“I do see that happening in the future, where a network of Remote ID location information leads to a more comprehensive unmanned air traffic management system,” Wallace says. For now: “If there is a high-interest event, like say, a Super Bowl or something, law enforcement or potentially even the FAA should have the ability to detect these signals using an application and then be able to enforce if someone is flying in a location where they’re not supposed to be.”

FAA requires new commercial drones be built with fail-safes that don’t allow flight without a functioning Remote ID transmitter, he says. And operators are required to land a drone immediately if it stops transmitting data. But if a bad actor wants to fly a drone without Remote ID, there may be little to prevent the use of older drones or modified drones.

Get the latest news about advanced air mobility delivered to your inbox every two weeks.

About paul brinkmann

Paul covers advanced air mobility, space launches and more for our website and the quarterly magazine. Paul joined us in 2022 and is based near Kennedy Space Center in Florida. He previously covered aerospace for United Press International and the Orlando Sentinel.

Related Posts

Stay Up to Date

Submit your email address to receive the latest industry and Aerospace America news.