Stay Up to Date

Submit your email address to receive the latest industry and Aerospace America news.

Submit your email address to receive the latest industry and Aerospace America news.

Nearly 10 years after its founding, Boom Supersonic earlier this year broke the sound barrier with its XB-1 subscale demonstrator — without generating a sonic boom. Cat Hofacker spoke to CEO Blake Scholl about Boom’s plan to automate this technique for its future passenger airliners.

Bringing back supersonic passenger travel was always going to be a tall order, but Boom Supersonic CEO Blake Scholl has set the bar even higher for the planned 2029 debut of his company’s Overture airliners: “I think everybody wants supersonic travel, provided it’s safe, it’s convenient, it’s comfortable, it’s sustainable and it’s friendly to the passengers and the people on the ground. Oh, and it’s got to be affordable,” he told me by video from his office in Colorado.

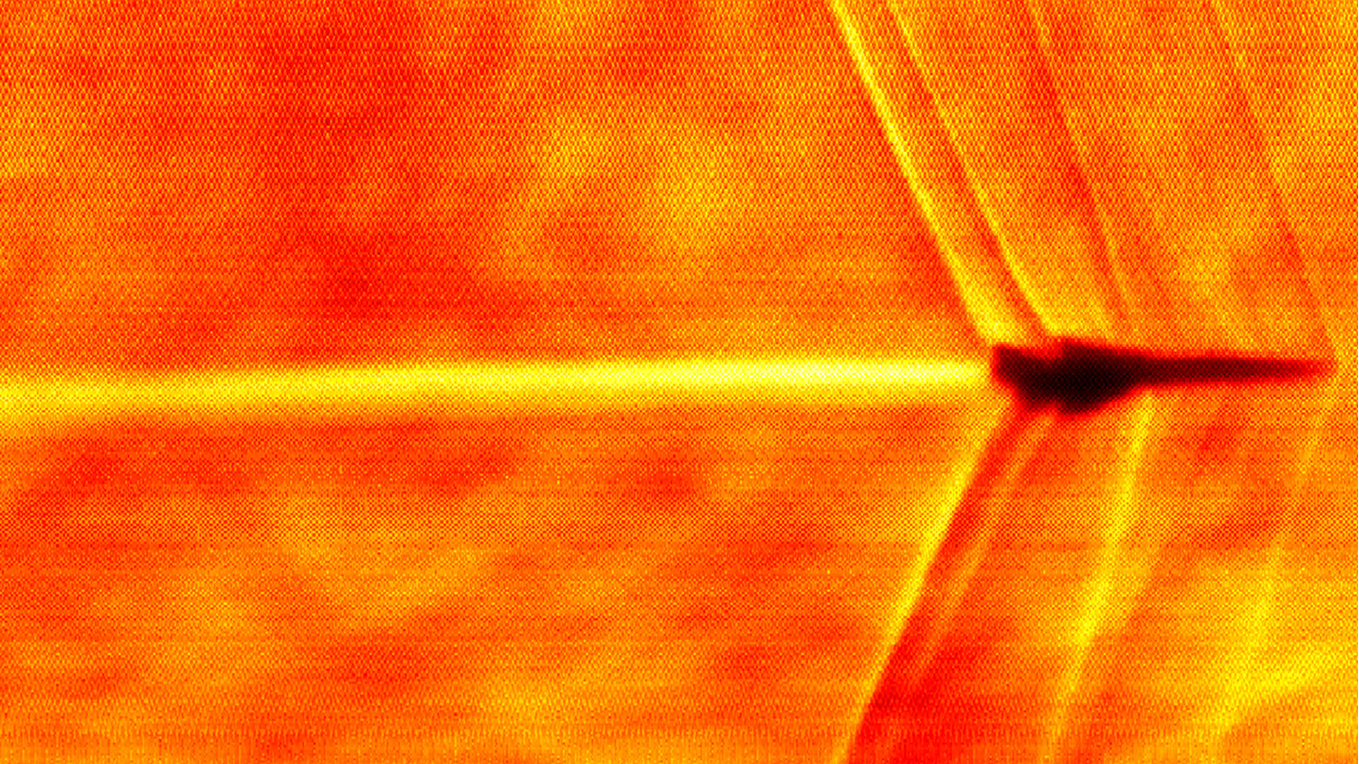

By “friendly,” he’s referring to the sonic booms produced when an aircraft breaks the sound barrier. Boom’s solution is one part flight planning, one part technology: Overture will only reach its top speed of Mach 1.7 over water. For overland flight — provided that FAA lifts the 1973 ban on civil supersonic flight — a collection of software algorithms in the flight computer must calculate the speed and altitude at which the sonic boom would be refracted away from the ground. Boom demonstrated this Boomless Cruise concept in January and February, flying its subscale XB-1 demonstrator silently over the Mojave Desert.

“The new era of supersonic flight is unlocked by carbon fiber composites and turbofan engines and advanced aerodynamics,” Scholl says, “But it’s also every bit as much unlocked by software and computers.”

In terms of physics, Boom is leveraging the well-known Mach cutoff phenomenon recorded by NASA and other organizations in high-speed flight tests going back to the 1950s.

“I’m sure we’ve all seen the middle school science experiment where you got a glass of water and you drop a pencil in the glass of water, and it looks broken,” Scholl says. Water is denser than air, so the light waves are bent, or refracted.

For aircraft, atmospheric conditions also factor in because of how the sound travels differently at colder, higher altitudes compared to the warmer atmospheric layers closer to the ground: “A boom as it travels through the atmosphere is going to curl, it’s going to refract, and it’s going to kind of turn upward. And if the angle is shallow coming off the airplane and the airplane is sufficiently high, [the boom] makes a U-turn in the sky and nobody on the ground hears it.”

The XB-1 demonstrator doesn’t have autopilot, so Boom engineers had to calculate ahead of time the required altitude and speed to achieve quiet supersonic flight over the desert. This isn’t practical for Overtures taking off and flying all over the world, and so Boomless Cruise was born.

“You need good weather data, which basically the world has now. You need a computer that can run real-time sonic boom predictions and calculate the right speed and altitude for any given day. Check, we’ve got that,” Scholl says. “And then number three, you need engines that can do it efficiently.” He’s referring to the Symphony engines that his company is designing in-house for Overture.

If the concept behind the flight control algorithms sounds familiar, that could be because Boom is not the only company to explore it. Nevada-based Aerion Supersonic announced its own boomless cruise concept in 2020 but declared bankruptcy about 18 months later, ending its plans to develop a supersonic business jet. Scholl acknowledges the similarities between the two concepts but points out that Aerion never flew an aircraft and “never actually proved they could do” boomless cruise.

— Blake Scholl, CEO, Boom Supersonic

The Overture flight deck design isn’t finalized yet, but Scholl envisions “Boomless Cruise” being one of the Mach hold settings that pilots can select on the flight deck. “And what that will mean is [the aircraft] will fly the fastest, quietest Mach, and it’ll speed up and slow down automatically in order to be as fast as it can be while not making a boom.”

Maintaining Boomless Cruise might also require an Overture to change its altitude throughout a flight, but Scholl says this will closely resemble the way that today’s aircraft make minor adjustments during cruise, which air traffic control deconflicts by giving each plane a “block clearance” of altitudes.

Overtures are being designed to cruise at up to 60,000 feet, so “we’re going to be the only ones at that altitude,” Scholl says. “And so you can imagine a whole row of Overtures, one after the other, but they’re all going to be flying the same Mach so the spacing is actually easy. This is not ATC’s biggest problem, not by any stretch.”

Speaking of problems, the U.S. prohibition on overland supersonic flight poses a potential hurdle, but it’s one that Scholl is confident will be removed well before 2029 because “everyone kind of wants to change it.”

“There are a lot of things in D.C. that are controversial, but this isn’t one of them,” he says. “If you’re going to have a sonic boom, people can argue about ‘Is it quiet enough or is it too loud, and should the threshold be this many decibels or that many decibels?’ Reasonable people can differ and will differ, but if there’s no boom, it’s really obvious.”

He adds: “Republican, Democrat, career staff or politician, I haven’t found anybody who thinks [the ban] should stay like it is. I think it’s going to happen really quickly.”

Even if the ban isn’t lifted, Boom has plenty to do in the meantime. With XB-1’s brief but eventful flight campaign concluded, it’s on to constructing the first Overture components.

“The high-level airplane design is frozen, and it’s all just a scale up of everything we learned from XB-1,” Scholl says. So the first thing you’ll see hardware wise is the engine. We’re building engine parts. Around the end of the year, we’re going to be engine running, and middle of next year, we’ll start building the first full-scale airplane. We were in a very exciting phase with XB-1 flying, and now it’ll go back a little bit to where XB-1 was a few years ago, where you’re seeing parts coming together, things are getting built on an airplane.”

"You can think of it as we have to eclipse the sun," says Scholl. Chief Test Pilot Tristan "Gepetto" Brandenburg "has to fly between the camera and the sun at the right time, at the right speed, plus or minus 250 feet for this to work — oh, by the way, flying the airplane at a speed it's never flown at before."

To achieve this, XB-1 software lead Jason Reicheneker created software to guide Gepetto to that required position. This JPS, short for Jason Positioning System, shows up as an arrow on XB-1's cockpit display and also includes a countdown timer.

"The thing I love about this is Jason had the idea and 13 days later, the software was written," tested and loaded onto the aircraft, Scholl says. "I don't know anywhere else in the industry where someone ships flight software in 13 days."

As the airframe comes together, Boom will also finalize the Overture flight deck based on input from the company pilots and pilots from United Airlines, which has an agreement to purchase 15 Overtures.

“If we’ve learned anything from just watching the well-publicized disasters of commercial airplanes in the last 10 years, it’s that pilots weren’t involved,” Scholl says. “So when we do technical reviews, United’s pilot corps is part of it.” On the flight deck, “they tell us what they like, what they don’t like, and we keep tweaking it.” He says Boom also sends its pilots for simulator training at United’s Flight Training Center in Denver.

Scholl, who earned his private pilot license in 2008, also took a few turns in the simulator. “I flew the 787, and the biggest thing I was struck by is how much more complicated it is than Overture. People think, ‘Oh, a supersonic jet, it’s more complicated.’ No, no, what’s complicated is a flight deck that is 50 years of one idea on top of another idea on top of another idea, where nobody ever said, ‘Hang on, let’s rethink the whole thing.'”

He goes deep about the 787’s attitude display: “It’s got a head-up display, and it’s got a primary flight display. Those both tell the pilot the same thing, but they’ve got different symbology. And the head-up display had like several different attitude indications. It’s got this one that looks like a W, it’s got another artificial horizon, and it’s got this thing that the pilots are calling the pizza and the pizza pan — I’m so confused. How about you give me one way to tell what the airplane is doing?”

We’re nearing the end of our allotted time, so I ask my final question: The first decade of Boom was devoted to achieving supersonic flight. Where does he want the company to be in 10 years?”

He has his answer ready: “Supersonic flight is commonplace. The initial supersonic flights, when you break the sound barrier, it’s going to be really exciting. Champagne will be served. There’ll be a celebration on board. But 10 years from now, so many people have flown supersonic so many times that the supersonic celebration is annoying. It’s just how we fly.”

Cat Hofacker helps guide our coverage and keeps production of the print magazine on schedule. She became associate editor in 2021 after two years as our staff reporter. Cat joined us in 2019 after covering the 2018 congressional midterm elections as an intern for USA Today.

Submit your email address to receive the latest industry and Aerospace America news.