Stay Up to Date

Submit your email address to receive the latest industry and Aerospace America news.

Every day, high-stakes work plays out in labs and test chambers across the aerospace community that doesn’t always get much visibility. Sometimes, that’s the way technologists want it for classification or proprietary reasons. More often, I suspect, it comes down to corporate culture and personality. I sometimes wonder if reusable rocketry might have continued to languish were it not for the strong personality and Twitter feed of Elon Musk, the SpaceX founder.

The reality is that not all companies and agencies have a Musk at the helm. That doesn’t mean that their work is not potentially impactful. If you look at our cover story and beyond, you’ll sense our efforts bring that work to light.

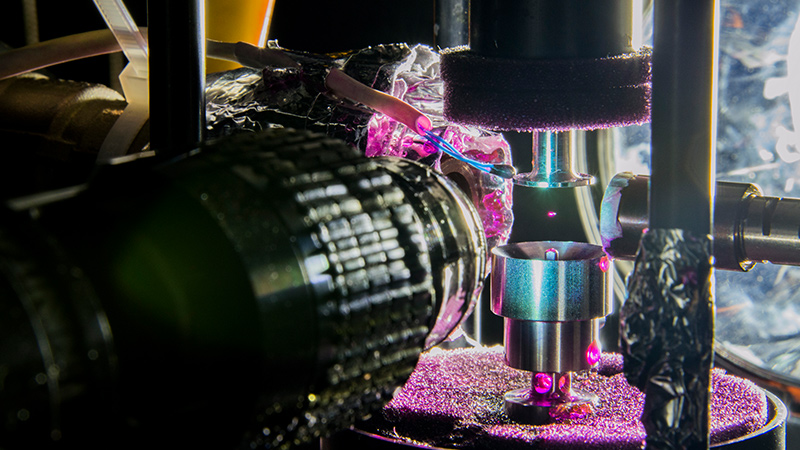

A case in point is the Penn State team that devised a technique for imaging partially melted ice crystals, the subject of this month’s Engineering Notebook. It would have been tragic if an airliner crashed someday because no one figured out how to fully study the physics of the partially melted crystals that cause this phenomenon. This imaging technique can’t solve the problem by itself, but it will be a great help.

Then there’s the CanX-7 satellite mission, described in our Trending section.

In one 3.6 kilogram package, these researchers managed to take on two hugely important issues.

They tested a drag sail technology that could prevent small satellites from becoming dangerous hunks of debris, and they demonstrated an alternative strategy for collecting identity and location information transmitted by aircraft. More fundamentally, CanX-7 proves that the semantic boundaries are breaking down between what constitutes a space technology versus an aviation one and the kinds of services that can be expected from a small satellite compared to a large one.

In the realm of space exploration, so much of the community is excited about the prospects of sending humans to Mars that it’s easy to forget that the NASA-funded Jet Propulsion Lab is working on the next robotic rover, Mars 2020, patterned largely after the Curiosity rover. If that team achieves its goal of gathering rock samples and covering more ground than Curiosity, its work could be a testimony to the power of improved algorithms and processing.

In fact, I can imagine a fiscally disciplined NASA freezing the physical designs of space probes and rovers to meet what’s required to explore a small set of specific destinations, whether a rocky planet like Mars or an icy moon shielding an ocean. New scientific discoveries could be achieved by tailoring the software and processors on the next iterations of these probes and rovers.

Editor’s note: In the photo at the top of this page, a research team at Penn State University suspended a droplet in midair with acoustic waves created by an ultrasonic levitator during a test examining the causes of aircraft engine icing.

About Ben Iannotta

As editor-in-chief from 2013 to March 2025, Ben kept the magazine and its news coverage on the cutting edge of journalism. He began working for the magazine in the 1990s as a freelance contributor. He was editor of C4ISR Journal and has written for Air & Space Smithsonian, New Scientist, Popular Mechanics, Reuters and Space News.

Related Posts

Stay Up to Date

Submit your email address to receive the latest industry and Aerospace America news.