Stay Up to Date

Submit your email address to receive the latest industry and Aerospace America news.

Blue Origin is preparing for a demonstration this year of a suite of technologies that could provide the foundation for future self-sufficient lunar settlements. Paul Marks spoke to the lead technologist of the effort.

In a sprawling laboratory complex in Los Angeles, researchers are developing technologies that could allow future lunar citizens to live off the land.

As Vlada Stamenkovic tells it, the instruction he and his colleagues received from their boss, Blue Origin founder Jeff Bezos, was a demanding one: “Show me that this is real, that it’s not just a dream.”

In other words, prove that it is possible to produce critical resources — breathable oxygen, rocket fuel and the metals and glass needed for solar panels and power cables — from nothing but moon dust.

“The idea of in-situ resource utilization was a kind of dream for many decades,” says Stamenkovic, senior director of the company’s Space Resources Center of Excellence in Los Angeles. “We have had to put our money where our mouth is and show that it works.”

There are now signs it’s beginning to. In September, Blue Alchemist, the company’s initial suite of eight lunar resource extraction technologies, passed a critical design review by NASA’s Space Technology Mission Directorate. NASA is involved because it has partly funded Blue Alchemist’s development with an award of $34.7 million.

“Making unlimited amounts of solar power, transmission cables and oxygen anywhere on the Moon supports both NASA’s lunar sustainability and Blue Origin’s commercial business objectives,” NASA says on its website.

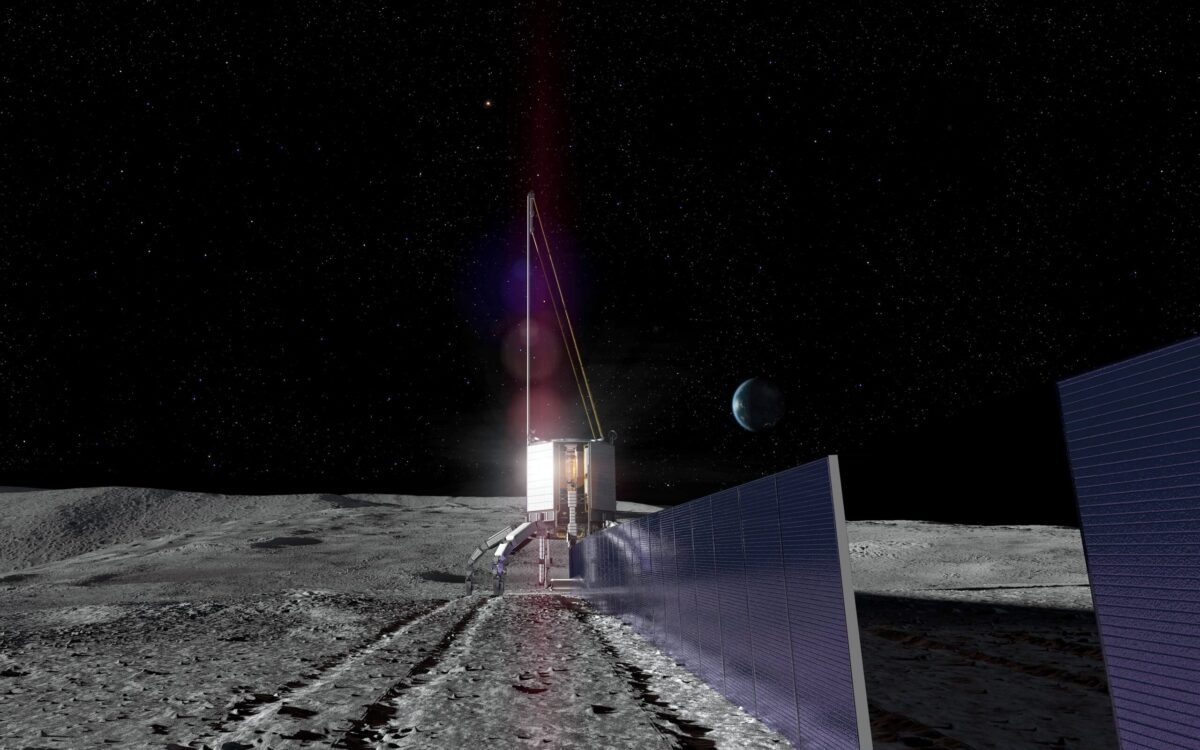

That CDR milestone cleared Blue Origin to plan for a “full end-to-end autonomous terrestrial demonstration” of Blue Alchemist sometime in 2026, says Stamenkovic. This will involve engineers placing their regolith reactors and robotic manufacturing systems in what he calls “gigantic” vacuum chambers.

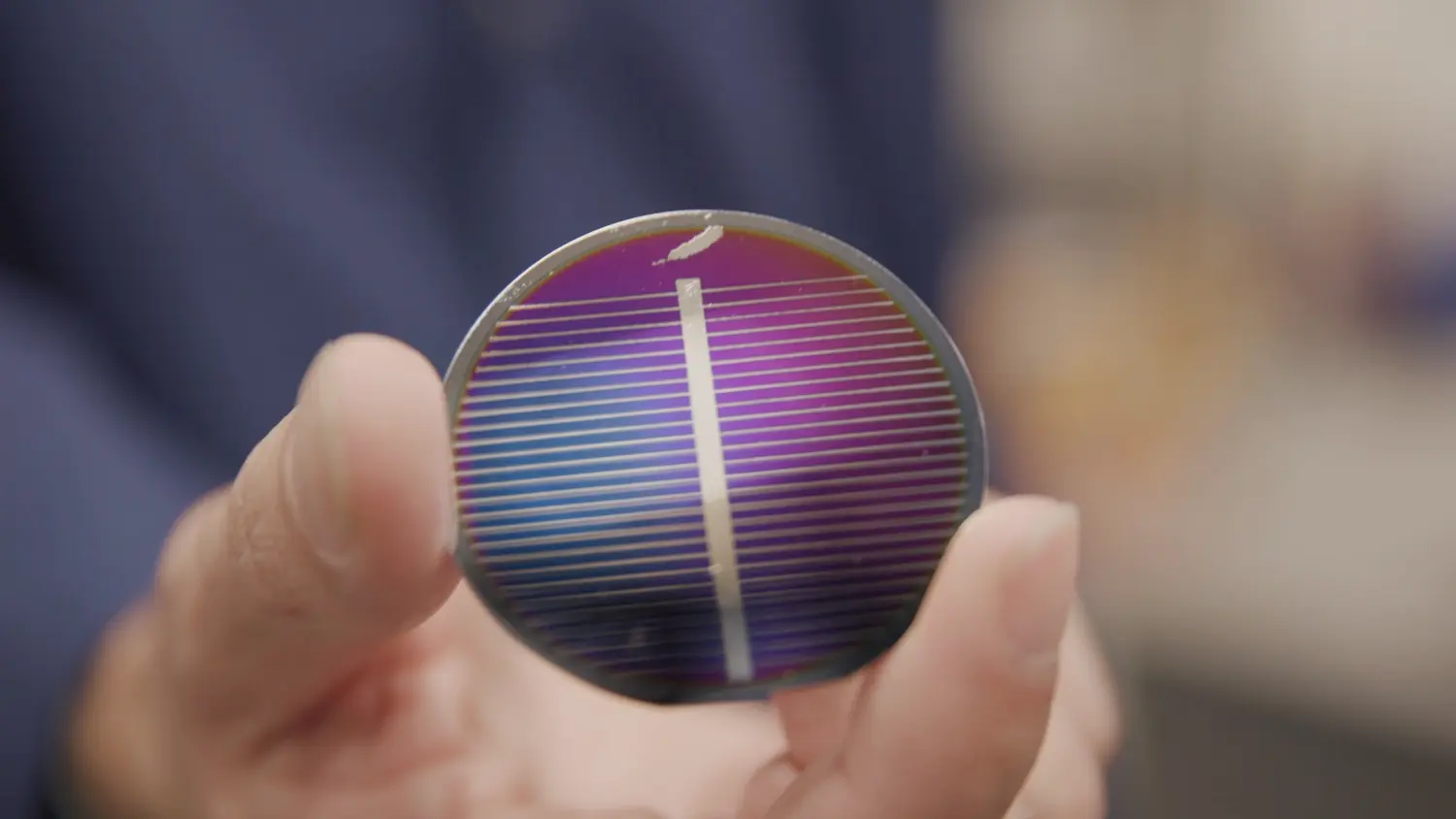

“We’ll put in different compositions of regolith simulants, and out of the other end will come a solar cell — and we won’t have touched anything,” Stamenkovic says.

If all goes as planned, Blue Alchemist will take moon dust in and push out products like solar cells, cables, air and fuel — all in one-sixth of Earth’s gravity, in a vacuum, and on a celestial body with punishing temperatures fluctuating between 120 degrees and minus 133 degrees Celsius.

A multipronged puzzle

For this task, Stamenkovic has assembled a host of multidisciplinary experts in Blue’s Los Angeles facility. The sprawling three-acre (5,500-square-meter) lab is home to a 70-person team that includes geochemists, petrologists, mineralogists, planetary scientists, semiconductor specialists, materials scientists and metallurgists — plus electrical, mechanical, robotics and computer engineers. As for how to foster collaboration among people with such diverse technical backgrounds, he says the key has been

focusing on the hard engineering problems that need solving for any moon settlement, rather than engaging in thought experiments over granular details like the size of a lunar colony and the designs of specific structures, from habitation modules to landing pads and data centers.

“I have stopped imagining and debating exactly what the vision looks like. There’s not enough data, and it’s all opinion anyway,” says Stamenkovic. “Instead, we have asked ourselves what will we actually need to live on the moon.”

One of the answers? A great deal of electric power. If lunar inhabitants are to be self-sufficient, they must extract their own water, breathable air, building materials, rocket fuels and the metal and glass needed for solar panels and cabling — from nothing but the rocks and regolith strewn around them.

For this reason, Blue Alchemist’s primary aim is to develop solar power systems that allow each lunar settlement to stably generate at least 1 megawatt of solar-electric power from locally produced arrays spread across the moon’s surface — almost seven times the power that the International Space Station’s solar arrays have grown to generate in its quarter century on orbit.

A lunar resources extraction plant will need to be at least an order of magnitude more power hungry for good reason: “Chemical processing involves breaking chemical bonds, and there is a minimum energy you need to do that. You can’t change it. So to sustain chemical processing on the moon, we need to get in the order of a megawatt to have an effect. That’s the scale we’ve decided on for stable power generation if we’re not to operate there in a pure survival mode,” says Stamenkovic. Long term, he’d like it to scale to a gigawatt.

The “chemical” at issue here is lunar regolith, an aggregate made of rock that’s been crushed over billions of years by relentless meteoroid and micrometeoroid impacts, and from bombardment by charged particles like protons in the solar wind and galactic cosmic rays. “Chemically and mineralogically, lunar rock is very similar to many Earth rocks and has a similar formation origin,” Stamenkovic says.

Like on Earth, the composition of a given sample of regolith depends on where it comes from. Take the moon’s once-volcanic mare regions, like the Sea of Tranquility that Apollo 11 landed in. There, the rock comprises largely silicon, iron and magnesium chemically bound to oxygen. In the highlands and south pole, the rock has a greater proportion of aluminum and calcium bonded to oxygen.

And 45% of the mass of the rock in both regions is oxygen, so Blue Origin is aiming to break that oxygen free from the other compounds and collect it as a propellant or for breathing. The liberated silicon and iron can then be turned into solar cells, the calcium and aluminum into power cable or solar panel conductors. (Although calcium oxidizes immediately on Earth, in the lunar vacuum it can’t, and it’s a great conductor.)

A great big melting pot

But how to perform this extraction? On Earth, feedstocks including coal and natural gas, plus a whole lot of water, have been heavily used in thermally driven processes to extract metals from rock ores. But as the whole idea here is to avoid feedstocks expensively launched from Earth, Blue Origin has — after what the company says was a thorough consultation with independent geochemists — opted for a lunar surface resource extraction approach using only in-situ energy, one called molten regolith electrolysis (MRE).

“In space, you do not want to rely on chemical processing methods requiring huge amounts of liquids or gases,” Stamenkovic says.

Instead, Blue Alchemist’s MRE reactor would use electricity from surface solar arrays to heat crushed regolith powder to 1,600 C, creating a melt that is thermally and electrically conductive. Electrodes would then pass a current through the melt, which has the effect of separating metal and silicon ions from the oxygen ions they were bound to. The positive metal and silicon ions migrate to one electrode and the negative oxygen ions to the other, where the gas bubbles off for collection as propellant or breathable air. To ensure it actually is breathable, Blue Origin is using flight metrology hardware from NASA’s Kennedy Space Center to assess the purity of the oxygen it extracts. If it’s tainted, a purification technology developed at Johnson Space Center can clean it up.

Stamenkovic thinks contaminated resources will be unlikely because Blue Origin designed the MRE reactor to have precision control over what is extracted at any one time. “The voltage across the electrodes corresponds to the energies that you require to break bonds. So by adjusting that voltage, we can separate specific metals and tap them off one by one. We start with iron, then the next stage is silicon, and then aluminum — and as a byproduct, we get glasses,” he says.

That glass is vital for the longevity of the settlement’s megawatt-scale solar power arrays. Without glass to cover them, the heavy solar radiation flux would destroy the panels “in a few tens of days,” according to the company’s calculations.

Simulate to gravitate

As all the company’s lab experiments must take place under Earth’s gravity, Blue is heavily relying on computational fluid dynamics (CFD) simulations to verify that the Blue Alchemist tech will work in the one-sixth g lunar environment.

“Lunar regolith is definitely going to be full of surprises,” says Stamenkovic. “One of the biggest risks is if there are differences in lunar gravity on different parts of the moon, how do we mitigate that?”

His team’s answer has been to simulate its way out of any such trouble by varying the geometry and dimensions of the reactor vessel CFD model in multiple ways, and simulating different shapes of electrode — such as star- and U-shaped ones — to adjust current density, the parameter that controls the speed of metal, silicon or oxygen production. Stamenkovic says the team is now confident it has optimized Blue Alchemist against any lunar gravity variation issues.

Is the team also confident, I asked, that the regolith simulant melting in their reactor is representative of what pioneering users will one day shovel into it on the moon? Having NASA as a partner helps here, Stamenkovic says, as Blue Origin has been able to compare the various regolith simulant compositions it tests with genuine regolith brought back from the Apollo landing sites.

“Although NASA only allows us a very little regolith to compare ours with, it’s a material that’s been so well studied we’re sure that our system will be able to handle all kinds of regolith,” says Stamenkovic.

“We can now build a system that’s going to go to the moon to make oxygen for astronauts, for fuel cells, and for propellant.”

About Paul Marks

Paul is a London journalist focused on technology, cybersecurity, aviation and spaceflight. A regular contributor to the BBC, New Scientist and The Economist, his current interests include electric aviation and innovation in new space.

Related Posts

Stay Up to Date

Submit your email address to receive the latest industry and Aerospace America news.