Stay Up to Date

Submit your email address to receive the latest industry and Aerospace America news.

While controllers in individual towers are managing the flights arriving at and departing from their respective airports across the U.S., FAA’s air traffic managers are tasked with overseeing the overall flow of traffic across the country — and ensuring any small delays don’t cascade into a widespread outage. Large language model tools in development at the University of Michigan could make this task easier, as well as help train managers on unusual scenarios. Keith Button spoke to one of the le

Max Li’s idea for artificial intelligence tools that could lighten the workload of FAA’s air traffic managers came to him two years ago over a cup of coffee.

The University of Michigan aerospace engineering professor was on a break during a conference, chatting with an officer who mentioned a common on-the-job frustration: Drafting certain types of air traffic plans, including those that manage weather-related delays at airports with complicated traffic patterns, could be a pain in the neck.

“This kind of got me thinking, and I shelved it in the back of my mind,” Li recalls.

That was the catalyst for Li’s development of a large language model AI for air traffic managers and, now, an LLM tool to help train them. If Li and his team are successful, the technology could make it easier for managers to create and tweak the ground delay plans that adjust aircraft departures in response to weather and other factors, to make traffic flow more smoothly when capacity is restricted at a particular airport. And the other tool could help instructors create novel scenarios in which air traffic is disrupted to help managers in training.

“We’re trying to look at: What are the things that these LLMs, generative AI techniques are good at, and how can we use them synergistically to relieve workload and relieve some challenges that human operators have?” Li says.

In the world of air traffic management, FAA-employed national traffic managers draw up the daily traffic flow plans and adjustments to those plans for the National Airspace System (NAS). While the air traffic controllers across the country are actively “pushing metal” in real time by directing takeoffs and landings and keeping aircraft separated in flight, Li says, traffic managers “are the worker bees in the nerve center, controlling the NAS from a broad strategic view.”

They start by developing an operations plan several days in advance for how each day’s traffic will flow, balancing demand and capacity for takeoffs and landings at the major U.S. airports. They later revise that plan as needed, based on a particular day’s weather forecast and other factors that would affect traffic or runway availability. These range from military flights to air traffic controller staffing shortages, or runway construction, space launches and even VIP travel.

When such events occur, managers issue a ground delay program, which sets a reduced arrival rate for the targeted airport and calculates the minutes of delay for each incoming aircraft. Those planes then have their departures delayed so they aren’t stuck flying a holding pattern above their destination.

Writing this program can be tricky, Li says, even for airports in which delays are common occurrences. Take New York City, where the complex airspace and fickle weather prompt managers to create ground delay programs at least once a week. Even so, Li says traffic managers have wondered aloud to him, “Why does it feel like we’re starting from scratch” every time?

A potential solution came to him in 2023, when the University of Michigan released U-M GPT. This set of internal LLMs — similar to ChatGPT — was available for university researchers to alter and adapt for their own projects. Could there be an LLM equipped to write ground delay programs? An air traffic manager “might not remember the specifics of the past 100 plans you’ve created, but perhaps a large language model trained on those plans could help you at least get over that initial writer’s block,” Li says.

At a glance, it seemed promising. LLMs are good at ingesting large sets of data and providing broad summaries in a readable format; humans are good at on-the-spot, nuanced decision-making. An LLM could provide the broad brushstrokes of a ground delay program based on similar circumstances encountered in the past, then the air traffic manager could write the detailed plan.

“It lets [the human managers] focus on what they’re getting paid for: their expertise,” says Li, who co-leads the project with University of Maryland professor Alex Estes. Rounding out the team is Ph.D. student Sinan Abdulhak, student researchers at Maryland and Cornell University and Wayne Hubbard, the FAA traffic management officer whose coffee conversation provided Li the initial inspiration.

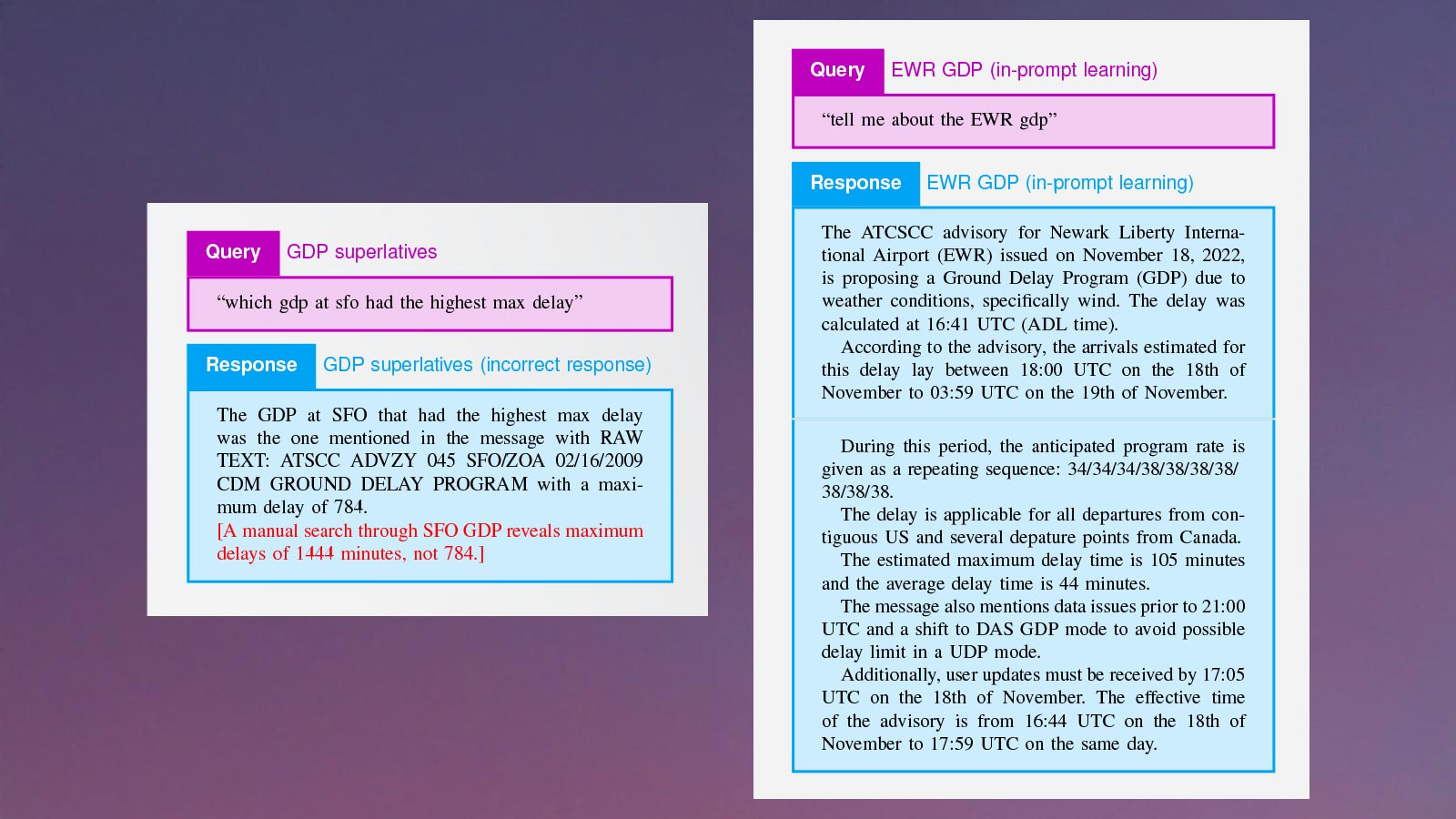

Over the last two years, they’ve trained their ChatATC model on 86,842 ground delay program text files issued from 2000 to 2023. Like ChatGPT, ChatATC was set up to answer conversational queries about past ground delay programs. As with other AI chatbots, ChatATC sometimes produces wrong answers, Li cautions, so the current version shouldn’t be relied on to make decisions or for any safety-critical roles.

As the development of ChatATC progressed, Li heard about another air traffic management challenge that potentially could be addressed by LLM: developing realistic training scenarios for rare situations. And so, late last year, work began on another tool.

Like ChatATC, this LLM — which doesn’t yet have a name — ingests data from past ground delay programs. But instead of discouraging the occasional tendency of LLMs to produce hallucinations, in this case, a degree of hallucinating is encouraged to make up situations that have never occurred before. Li’s team presented its work in June at the U.S.-Europe Air Transportation Research and Development Symposium and published a corresponding paper, “Generative Stress-Testing for Air Traffic Management Resilience.”

The idea is to create novel yet realistic scenarios of air traffic disruptions, and to provide the answer — meaning, the appropriate response by traffic managers. Li compares it to training the software for a self-driving car: “The important stuff isn’t the 99.9% of the times when you’re driving safely on the road, it’s that 0.001% when a cat runs out on the street or a kid comes out on the street. It’s that really rare instance that you want to train on.”

An LLM is needed to create these uncommon scenarios because there aren’t enough real-life examples from history to draw from, he says. And although humans today create training scripts themselves, he estimates that each takes 15-20 hours to write.

The researchers must walk the fine line between ensuring that the made-up scenarios are tricky enough to challenge in-training managers while still being in the realm of possibility.

“You don’t want to give people 10 examples of Mount St. Helens erupting and disrupting traffic in the Pacific Northwest,” Li says. “We wanted to get to a point where if you’re a traffic management officer and I put in front of you two scenarios — one is actually from the LLM and one is from some day in the past two or three years — I want them to not be able to tell it apart.”

To ensure the LLM was generating scenarios within a probable range of real-world conditions (think wind speeds, precipitation levels and thunderstorm locations) they built quantitative models based on data from past weather events and traffic delays, which generated random but realistic figures to represent scenarios numerically. They fed those numerical scenarios into the LLM, which was free to hallucinate scenario scripts, but within the realistic bounds set by the quant models, Li says.

In the future, they want to create scripts for disruptions from special events, like a Super Bowl or total solar eclipse, as well as expand the scenarios to include calculations of in-flight route capacities.

An air traffic management professor who isn’t affiliated with Li’s or other LLM research says the training tool seems promising.

“I think there’s viability there in terms of training purposes,” particularly for tabletop exercises, says Michael McCormick, a professor at Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University and a former vice president in FAA’s Air Traffic Organization, who at my request reviewed the papers by Li’s team.

The LLM training tool “can make it very dynamic so that it becomes more of an exercise and a challenge for the participants,” he adds.

However, McCormick says he sees less promise for the ChatATC concept, mainly because, in his view, ground delay programs are relatively easy to analyze, write and monitor. “It’s fun, but I don’t see where it is going to do anything revolutionary or even evolutionary.”

Going forward, Li and his researchers plan to incorporate user feedback to refine ChatATC and the training tool. This includes building an interactive web application for the training tool that will enable them to conduct experiments on the best ways to prepare traffic managers for severe disruptions. So far, they’ve built a phone app for ChatATC that could be adopted for research with a wide audience of FAA national traffic managers or airline operations managers who provide input on the NAS daily operations plan. That research could begin in 2026, Li says.

In the long term, he envisions ChatATC evolving from merely “a glorified chat bot” that summarizes knowledge from the past, into a suggestion box-like role that presents three or four ideas.

“Maybe two of them are completely unhelpful, but maybe the other two spark a decision in a human air traffic manager that he or she wouldn’t have thought of before,” he says. “The human could then go back and say, ‘Hey, that third suggestion you gave me, that was really good, but I made some modifications.’ And that becomes part of the feedback process.”

About Keith Button

Keith has written for C4ISR Journal and Hedge Fund Alert, where he broke news of the 2007 Bear Stearns hedge fund blowup that kicked off the global credit crisis. He is based in New York.

Related Posts

Stay Up to Date

Submit your email address to receive the latest industry and Aerospace America news.