Stay Up to Date

Submit your email address to receive the latest industry and Aerospace America news.

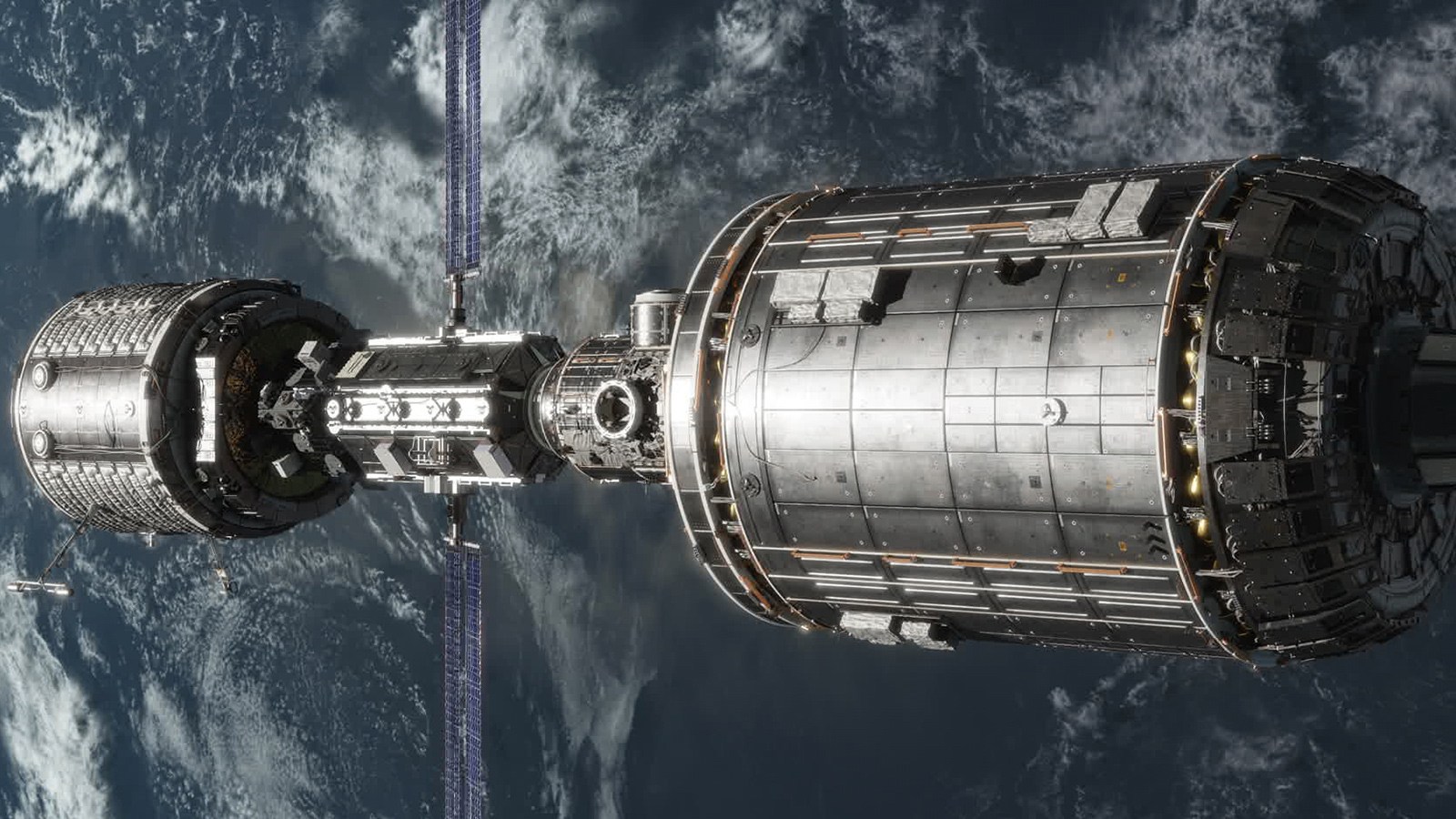

Technical consultants were key in shaping storylines, depictions of technology for fictional Mars mission

Writers and artists who created the Hulu series “The First” about a human mission to Mars avoided technological inaccuracies by running ideas past numerous consultants, including current and former officials at the NASA-funded Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

Realism was a top goal from the beginning, said Jordan Tappis, executive producer of the show on Hulu that stars Sean Penn; it premiered on Channel 4 in the United Kingdom on Thursday and in the U.S. in September. Tappis said the production team began by researching and writing “a nearly 700-page Mars bible that was circulated to each new cast and crew member.” It included details about the planet’s climate, robotic landers sent there and hazards humans could face during a mission to Mars.

“Despite all of our research, we were amateurs,” Tappis said, explaining that the production team reached out to consultants for “every creative choice that involved technical elements.”

The production team’s original ideas were based in reality but needed revisions, according to two of the show’s consultants, Charles Elachi, who directed JPL from 2001 to 2016, and Adam Steltzner, the chief engineer of the Mars 2020 rover project.

“It was very common for the art department to come in with something that looked very slick,” says Steltzner, adding he was “sort of an arch-critic” pointing out inaccuracies when artists ran ideas past him and Elachi.

“It’s got to have solar panels, it’s got to have an antenna,” he recalled telling the art department about concepts for the spacecraft that carries characters to Mars.

Stelzner joined JPL in 1991 and has been part of missions that landed four vehicles on the surface of Mars, including the Curiosity rover. He pointed out that rover and spacecraft concepts didn’t need fairings unless there was a specific need for them such as aerodynamics or safety, adding “form should follow function.”

In the real world of space design, a piece of equipment is “going to look however it needs to get the job done and style is not something that is considered,” he said.

The production team wanted a dramatic storyline that would have an arc over several episodes and affect the second season, which is in the early stages of being created. At the same time, the team needed to avoid unrealistic dramatic license. Elachi and Stelzner suggested the real-life risk of controllers on Earth losing communications with machinery sent to the red planet.

If all the equipment built for the Mars mission worked perfectly, “any engineer would tell you that’s unrealistic,” said Elachi, who is a professor of planetary science and electrical engineering at the California Institute of Technology and is still involved with JPL as a scientific researcher. “No matter how good you are and how much preparation you have ahead of time, you are going to have some anomalies.”

The storyline created with their input was about how engineers on Earth cannot connect with the Mars Ascent Vehicle sent to the surface of Mars ahead of astronauts, increasing the probability that astronauts may not be able to return to their spaceship and travel home.

Elachi also told writers “about how we did Curiosity, Spirit and Opportunity, and the challenge we had in convincing Congress of the value of these [rover] missions” during his time as JPL director. This helped the writers create an undertone of political challenges faced by NASA and the fictional space contractor Vista.

In the Hulu image at the top of the page, astronauts in the TV show “The First” float inside the Mars Transit Vehicle preparing to travel to Mars.

About Tom Risen

As our staff reporter from 2017-2018, Tom covered breaking news and wrote features. He has reported for U.S. News & World Report, Slate and Atlantic Media.

Related Posts

Stay Up to Date

Submit your email address to receive the latest industry and Aerospace America news.