Stay Up to Date

Submit your email address to receive the latest industry and Aerospace America news.

Agency expresses confidence in meeting 2024 deadline

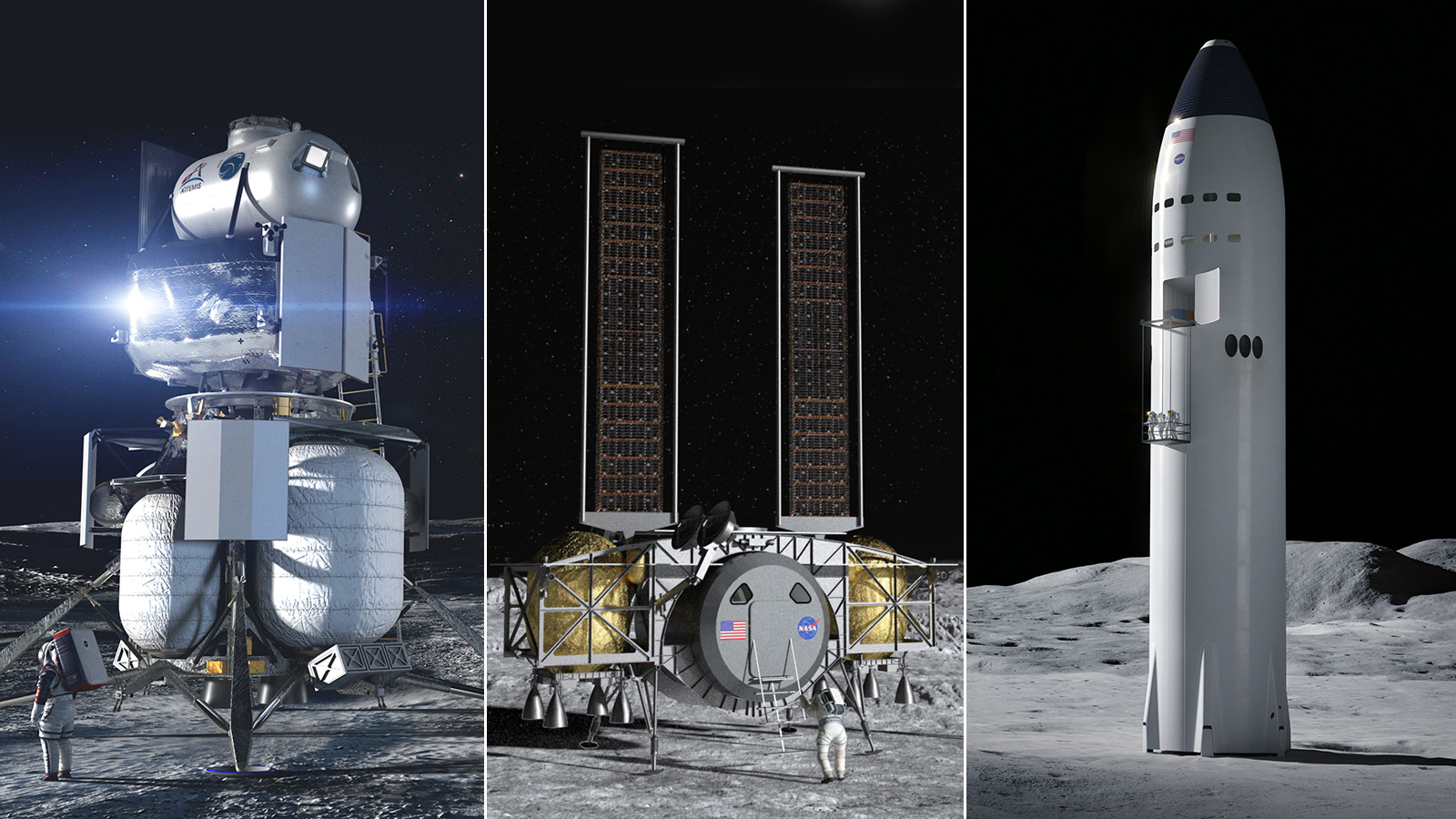

In its desire to return Americans to the moon, NASA has selected three distinct lander designs for further work, indicating the agency is embracing flexibility as it works toward the first landing, scheduled for 2024, and others to follow.

The agency awarded a combined $967 million to Blue Origin, Dynetics and SpaceX to refine their concepts for Human Landing Systems and define the tests that will be required to prove their safety. By choosing “notably different architectures,” NASA will “achieve the innovation and dissimilarity in redundancies” that will increase its chances of success, said Lisa Watson-Morgan, program manager of the Human Landing System effort, during a call with reporters today.

Parts for Blue Origin’s three-part lander, for instance, can be launched individually on Blue Origin’s New Glenn rocket or United Launch Alliance’s Vulcan, “or combined to launch on NASA’s Space Launch System,” according to a NASA press release.

Similarly, the two-part lander from Dynetics would be built in such a way that it can launch on a number of commercial rockets.

SpaceX’s lander, Starship, would be launched as one unit and would be fully reusable with the ability to launch 100 tons of cargo to the lunar surface, along with crew, according to SpaceX and NASA.

After February 2021, NASA will choose two or all three of these landers for further funding, betting that at least one of them will be ready for 2024. But the landers not chosen for the 2024 mission will not go to waste, said NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine during the call with reporters. If all goes according to plan, the 2024 mission will lay the groundwork for a permanent U.S. presence on the moon, and eventually a human mission to Mars.

Bridenstine said bold aspirations are needed now more than ever, given the coronavirus pandemic.

“We need to give people hope, we need to give them something that they can look up to, dream about, something that will inspire not just the nation but the entire world,” he said. “That’s what NASA does.”

Without mentioning names, the agency appeared to push back on lawmakers of both parties who have questioned the program’s audacious deadline of 2024 for landing the crew of a man and a woman. “We are very confident we can get this done in the next four and a half years,” said Doug Loverro, NASA’s associate administrator for human exploration.

In the year since the Artemis program was announced, NASA has continually refined its plans for the 2024 landing in an effort to meet the deadline. The original plan called for the astronauts and lander to ride to space on separate rockets and dock at the lunar Gateway, a planned space station that would be assembled in lunar orbit. Now, NASA intends for the landers to dock directly with an Orion capsule that would be launched with a crew ahead of time. This way, the mission would not have to wait for the Gateway to be completed.

“The Gateway is important for NASA, but it is certainly not necessary for the 2024 moon landing and I would say it’s not likely, although we’re not taking it off the table” just yet, Bridenstine said.

This and other decisions will be made over the next 10 months, he said, as contractors work with a team at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Alabama to refine their lander designs.

The first three months specifically will be spent on “how are we going to make sure these systems are certifiable for humans,” Watson-Morgan said. Much like the Commercial Crew program, contractors will propose which tests are needed for the landers, with NASA having the final say. Blue Origin and SpaceX have proposed completing an uncrewed landing on the moon, and Dynetics has suggested an in-flight demonstration of some kind, Watson-Morgan said.

About cat hofacker

Cat helps guide our coverage and keeps production of the print magazine on schedule. She became associate editor in 2021 after two years as our staff reporter. Cat joined us in 2019 after covering the 2018 congressional midterm elections as an intern for USA Today.

Stay Up to Date

Submit your email address to receive the latest industry and Aerospace America news.