Stay Up to Date

Submit your email address to receive the latest industry and Aerospace America news.

A partnership of industry groups and U.S. government agencies is on track to test and select an unleaded aviation gas that, in 2018, would be ready to replace today’s leaded general aviation fuels, FAA says. It remains to be seen, however, whether the Trump administration’s EPA will move to ban general aviation fuels containing toxic lead additives that enter the environment in engine emissions.

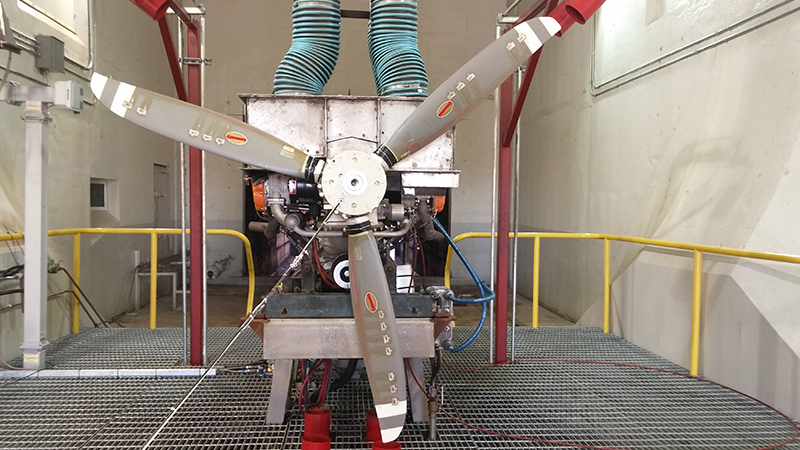

The Piston Aviation Fuel Initiative group in 2016 began flight testing two unleaded fuel candidates in 10 aircraft, and operating 15 engines in a test chamber with help from different manufacturers. The fuels designed by Swift Fuels of Indiana and Shell Oil Co. must have the right chemicals to pair with engines on all general aviation aircraft without causing mechanical failures.

Today, lead is added to aviation gas for piston engines to ensure safer compression performance that would prevent uncontrolled fuel detonation, or engine knock, which can cause engine failure in midair. Today’s fuels are designated as low lead, but they have enough of the toxic metal to concern environmentalists and health officials. The challenge is finding a mix of chemicals that prevents knock but is also affordable, cleaner burning and noncorrosive for machinery, says Peter White, manager of FAA’s alternative fuels program. In the test flights, pilots at the FAA Tech Center in Atlantic City, New Jersey, and at facilities owned by aviation firms are checking the fuels for compatibility issues with the different aircraft.

“Progress has been slower than I’d like but we are on schedule,” White says. “When you are blending a fuel from scratch without lead it’s a much more complex endeavor and you wind up trading off all these performance properties.”

Car drivers have for decades fueled their vehicles with unleaded gasoline, but safety concerns about engine knock earned an exemption for general aviation aircraft under the Clean Air Act, while leaded gasoline was barred for other modes of transportation.

The Environmental Protection Agency has documented that prolonged exposure to lead in air, water or dust can cause the metal to build up in the bloodstream and result in health problems like brain damage or kidney failure. With millions of people living near airports that host piston planes, environmental groups in 2006 petitioned the EPA to determine that leaded aviation gas endangers public health. In 2016, when there was no response to the petition, one of the petitioners, Friends of the Earth, joined a lawsuit filed by Earthjustice against EPA seeking a federal rule that would recognize leaded av gas emissions as a danger to public health.

Environmentalists have been frustrated with the EPA’s timeline. The agency started the Piston Aviation Fuel Initiative in 2013 with the FAA and aviation industry members, and later set 2018 as the earliest possible date for a final rule regulating leaded aircraft emissions.

The Trump administration’s EPA leadership is reviewing pending actions and setting priorities for the agency’s regulatory agenda, says EPA spokeswoman Christie St. Clair. .

Environmentalists are concerned that a ban might not be forthcoming, given the Trump administration’s moves to roll back environmental protections, and its proposal to cut EPA’s funding by 31 percent and staff by 19 percent. If EPA resists a ban, “we might have to go back to court,” says Marcie Keever, legal director of Friends of the Earth.

White, the FAA manager for the fuel project, says it is unlikely that a new fuel would take hold in the market if the EPA’s rulemaking process does not brand aviation gas as a danger to public health. If the new gas is more expensive than existing leaded gas and there is no EPA ban, White predicts that fuel suppliers won’t face the same pressure to sell the chosen replacement nationwide. Nonfederal agencies might in theory step in to ban leaded fuel, but “state and local activity would drive a much more slow and disorderly transition.”

For flyers, the new fuel could require some getting used to. The FAA initiative is unlikely to produce a direct “drop-in” replacement for the existing leaded fuel, White says, so pilots may face minor trade-offs including factoring in the extra weight of the chemicals that would replace the lead compound in av gas. “The original goal of the program was to find a drop-in replacement without the lead but nobody has been able to come up with that yet,” he adds.

“When you are blending a fuel from scratch without lead it’s a much more complex endeavor and you wind up trading off all these performance properties."

Peter White, manager of FAA’s alternative fuels program

About Tom Risen

As our staff reporter from 2017-2018, Tom covered breaking news and wrote features. He has reported for U.S. News & World Report, Slate and Atlantic Media.

Related Posts

Stay Up to Date

Submit your email address to receive the latest industry and Aerospace America news.