Stay Up to Date

Submit your email address to receive the latest industry and Aerospace America news.

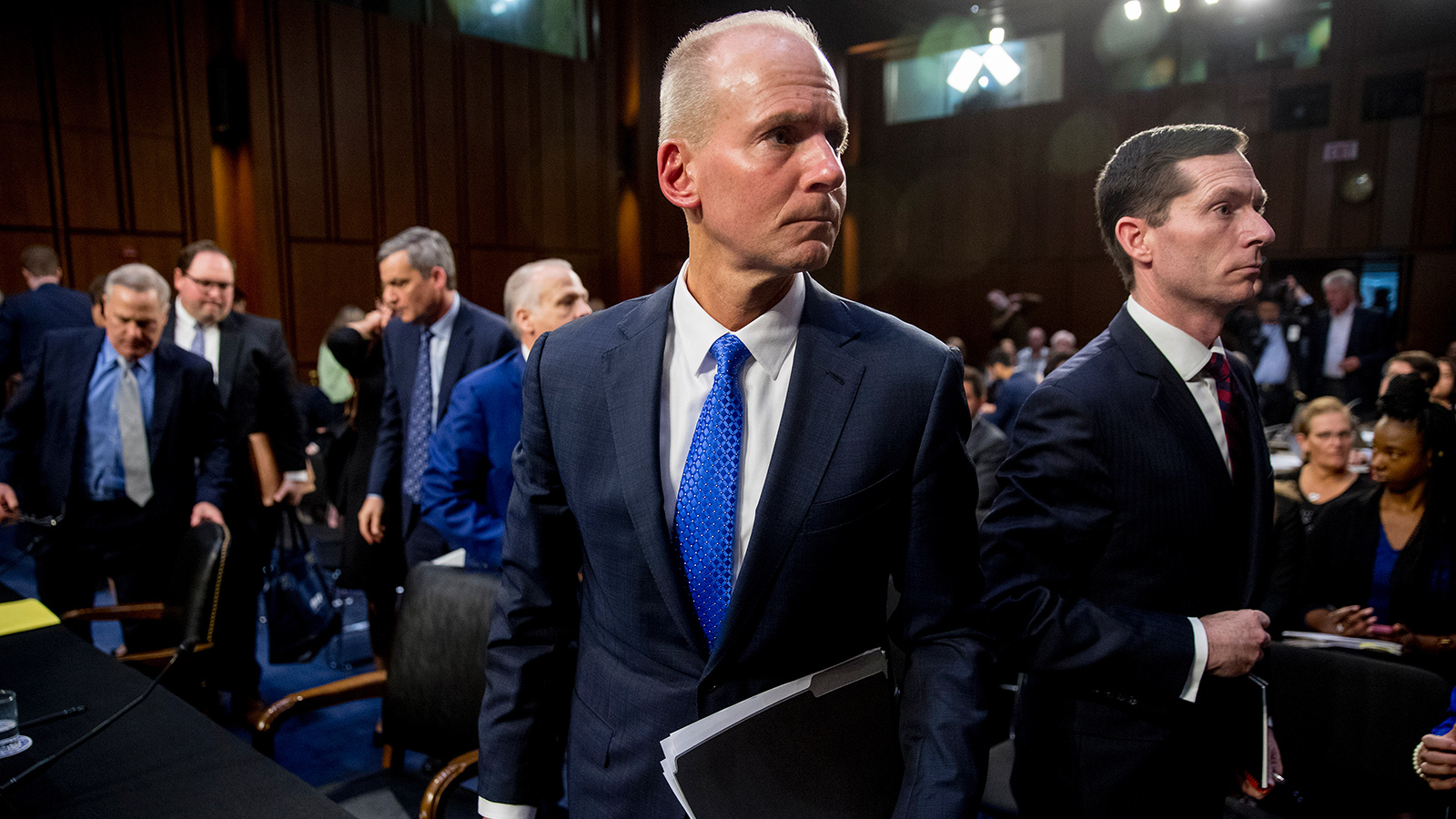

Boeing CEO defends process but expresses openness to refining it

Boeing CEO and President Dennis Muilenburg today resisted congressional calls for a complete overhaul of the FAA regulations that gave Boeing a large role in certifying the 737 MAX jets for commercial flights.

“We need to get the balance right” between government oversight and delegated authority to manufacturers, Muilenburg told senators during his first congressional appearance since the Boeing 737 MAX crashes that killed 346 people.

In the aftermath of the Lion Air and Ethiopian Airlines crashes that prompted a worldwide grounding of the MAX, the certification process has come under fire from lawmakers. Of particular concern to members of the Senate Commerce Committee during today’s hearing was the Organization Designation Authority, or ODA, program under which the FAA can streamline certification by delegating employees of companies like Boeing to sign off on many aspects of an aircraft’s design, including the Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System, or MCAS, the anti-stall software implicated in the crashes.

Senators of both parties questioned Muilenburg about ODA certification and whether it needs to be overhauled.

“I support taking a hard look” at ODA, Muilenburg said during questioning from Sen. Richard Blumenthal, D-Conn.

“I’m not asking you to take a hard look,” Blumenthal snapped. “Isn’t the certification process broken?”

Muilenburg said the delegation of authority process has “enhanced safety over the last couple of decades,” but “that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t refine it.” He said the “fundamental process is a strong process,” although he also said, “I think [the corporate-government balance] can be improved.”

Committee chairman Sen. Roger Wicker, R-Miss., noted that ODA has been used to certify many aircraft, but he questioned if the program allowed for an “inappropriately close relationship” between the FAA and Boeing.

After the second crash, the FAA ordered Boeing to put the MCAS software through a recertification process that must be concluded before flights can resume. Muilenburg told senators that Boeing is in the “final stages of that process.” The company has developed a software update for MCAS, as well as “some additional safety enhancements” that Muilenburg did not provide details about.

“This is all work we’re proceeding on over the next few weeks and months,” but the MAX return to service isn’t “timeline driven,” he said.

Even if the MAX jets are cleared to fly, the circumstances surrounding the MAX certification and the two crashes continue to be investigated by the U.S. Justice Department, multiple congressional committees and international regulators.

“This hearing will by no means end our inquiry,” Wicker said.

Nor is it the end of Muilenburg’s congressional testimony. He will appear tomorrow before the House Transportation Committee to discuss the MAX’s design and development.

More from the hearing

Muilenburg also faced questions from senators about news reports that Boeing pilots knew MCAS presented a possible danger before the Lion Air crash in October 2018. Earlier this month, Reuters published an instant message conversation from 2016 between then-chief technical pilot Mark Forkner and a colleague in which Forkner said MCAS was “running rampant” in simulator tests of the software and he had “lied to the regulators (unknowingly)” about it. In both MAX crashes, the crews struggled to regain control of the aircraft after MCAS erroneously activated, repeatedly pitching the nose of the aircraft down.

Boeing turned over documents containing the 2016 conversation to the U.S. Justice Department in February, but Muilenburg told the Senate Commerce Committee he first learned about the specifics of the conversation “a few weeks ago” when the messages were published.

Given those messages, why didn’t Boeing speak up about MCAS after the Lion Air crash, asked Sen. Ron Johnson, R-Wis.

It seems like “there were some people who know exactly or suspected what went wrong” in the immediate aftermath of the Lion Air Crash,” Johnson said. “Why didn’t you react faster?”

Muilenburg said he’s “not sure what was meant” in those messages.

FAA relationship

At the heart of senators’ criticisms of the Organization Designation Authority, or ODA, program under which FAA delegated Boeing employees to sign off on aspects of the MAX design is the question of whether Boeing had undue influence in the certification process for its own aircraft.

“It’s absolutely clear it’s too cozy of a relationship between the FAA and your airline, so what are you going to specifically commit to in terms of reform?” said Sen. Tom Udall, D-N.M.

Boeing Chief Engineer John Hamilton, seated next to Muilenburg, pushed back.

“We have a respectful relationship with the FAA,” and there are cases where “we do have our differences of opinion. It’s not a cozy relationship. It’s a professional relationship.”

He continued: “In terms of things I think we need to change, we need to revisit some of these regulatory guidances and see that they’re up to date.”

Hamilton was referring to FAA standards for how quickly pilots will respond to cockpit alerts that Boeing designed MCAS around. Boeing assumed pilots would be able to respond within three seconds of an erroneous MCAS activation, an assumption that’s been criticized in reports by the U.S. National Transportation Safety Board and the Joint Authorities Technical Review, an international group of regulators that examined the certification of the MAX.

The NTSB report found that in simulator tests that emulated an MCAS firing, Boeing did not simulate an angle-of-attack failure, “which would have led to numerous other alerts and warnings in cockpit” that wouldn’t be present in other situations, NTSB Chair Robert Sumwalt told senators during the second part of the hearing.

Changes to MCAS

During his testimony, Muilenburg told the committee that “we share your commitment to aviation safety.” To that end, he highlighted three changes in the MCAS design:

- In the MAX crashes, MCAS commanded the horizontal stabilizer on the tail of the aircraft to swivel upward in response to data from one angle-of-attack sensor that measures the angle between the aircraft and oncoming air flow. In the future, MCAS will only activate if it receives matching data from both AoA sensors on the fuselage of the MAX.

- The new version of MCAS will activate only once. The accident crews struggled against the software as it activated repeatedly, driving the nose of the plane down over a dozen times.

- Boeing assumed pilots would be able to override MCAS by flipping the thumb switches on the control column to pull the nose back up, which proved impossible during the crashes. Once MCAS is recertified, pilots will be able to override MCAS “at any time,” Muilenburg said.

About cat hofacker

Cat helps guide our coverage and keeps production of the print magazine on schedule. She became associate editor in 2021 after two years as our staff reporter. Cat joined us in 2019 after covering the 2018 congressional midterm elections as an intern for USA Today.

Related Posts

Stay Up to Date

Submit your email address to receive the latest industry and Aerospace America news.