Stay Up to Date

Submit your email address to receive the latest industry and Aerospace America news.

The rhetoric of the U.S. vice president and JFK were similar, but the times are not

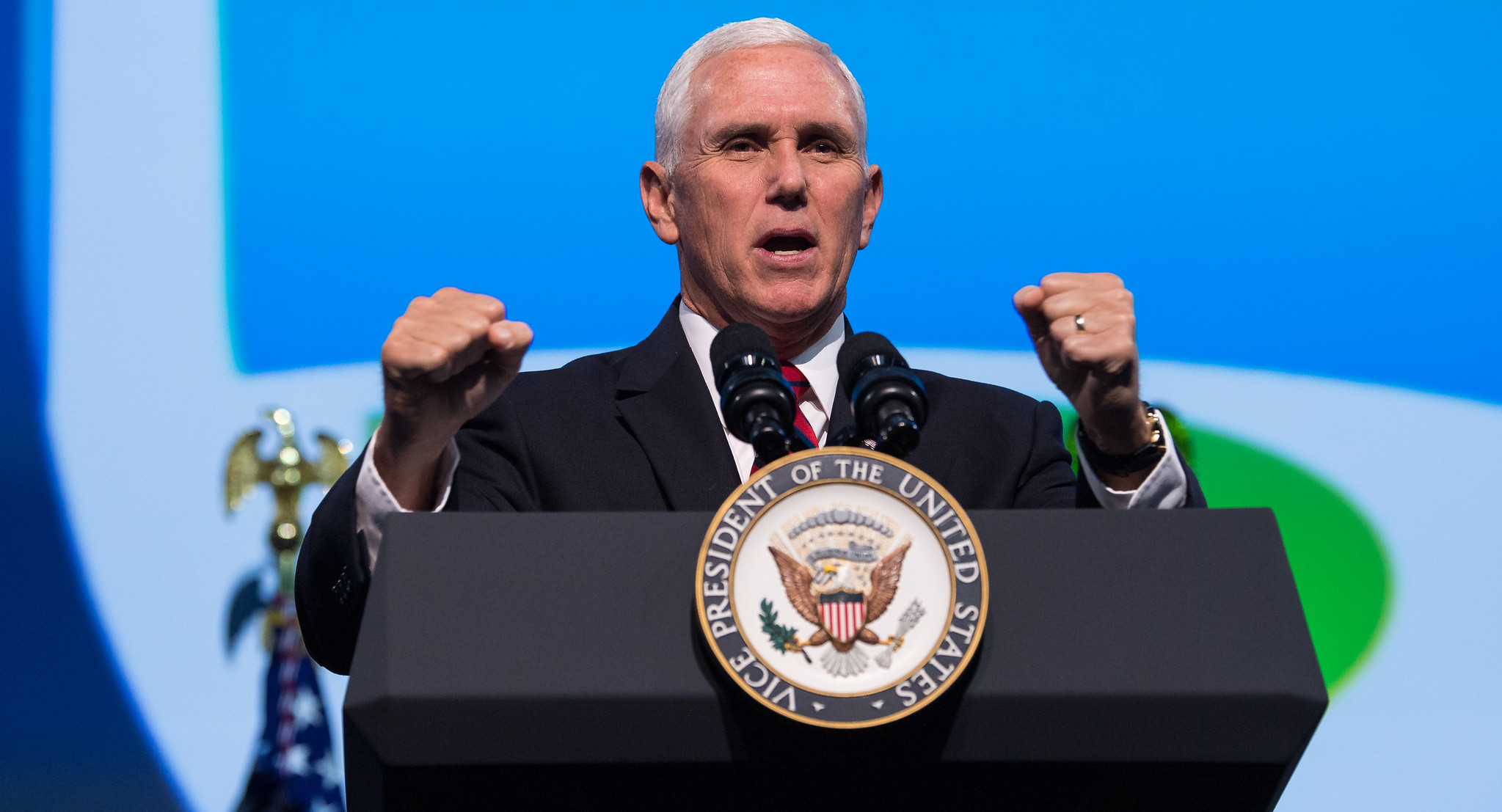

INTERNATIONAL ASTRONAUTICAL CONGRESS, Washington, D.C. – U.S. Vice President Mike Pence’s reference to “renewing American leadership in space” and his declaration that the United States is “the leader amongst freedom-loving nations” drew murmurs and little applause from the international audience of space leaders and enthusiasts who gathered in the Washington Convention Center ballroom Monday to hear him start the week’s events.

The audience reaction was almost surely colder than what President John F. Kennedy would have received had this been the 1960s and the topic were Apollo instead of Artemis, NASA’s plan to return U.S. astronauts to the moon in 2024. I wondered if it was Pence’s words that accounted for this reaction or some other factor.

My review of the late president’s speeches and my discussions with historians show that Pence’s remarks were quite similar in some ways to those of Kennedy, although with an America-first tone.

Here is Pence wishing the audience well: “I hope you will leave America’s capital with confidence that America is leading in space again, and that we are determined to lead — be the leader amongst freedom-loving nations into the vast expanse of space.”

Here is a passage from Kennedy’s 1962 address at Rice University in Texas, during which he uttered the famous “we choose to go to the moon” phrase: “In short, our leadership in science and in industry, our hopes for peace and security, our obligations to ourselves as well as others, all require us to make this effort, to solve these mysteries, to solve them for the good of all men, and to become the world’s leading space-faring nation.”

Both men shared a common view that U.S. leadership was uniquely needed to ensure freedom in space.

Pence said that “as more nations gain the ability to explore space and develop places beyond Earth’s atmosphere, we must also ensure that we carry into space our shared commitment for freedom and the rule of law and private property.”

Kennedy struck a similar theme in his Rice speech: “For the eyes of the world now look into space, to the moon and to the planets beyond, and we have vowed that we shall not see it governed by a hostile flag of conquest, but by a banner of freedom and peace.”

There does appear to be one marked contrast between the rhetoric of the two men. Pence ended his IAC address by declaring that “with God’s help, [the United States] will lead the world into the vast expanse of space once again for the benefit of all mankind.” Pence closed his August address at a meeting of the National Space Council with the same invocation of “God’s help” in space exploration.

Referring to God in this way seems to be unique to Pence. Kennedy made only one reference to God and space exploration that I could find, and the comment was not placed in the context of American leadership. Kennedy ended his Rice speech by asking for “God’s blessing on the most hazardous and dangerous and greatest adventure on which man has ever embarked.”

(Story continues below)

The audience reaction, it seems, could spring not from Pence’s word choice but from the broader community’s more collaborative mindset toward space in 2019 compared to the 1960s.

The political context of Pence and Kennedy’s rhetoric are very different, says John Logsdon, space historian and author of a book on Apollo 11 policy.

In the 1960s, “the world was divided in a zero-sum way between the U.S. and the Soviet Union, and space was new and its impact uncertain,” Logsdon says. Now, the U.S. has a variety of international and commercial partners in space, Russia being one of the most prominent.

“It’s clear that Kennedy saw [Apollo] as a geopolitical response to Soviet confrontation,” Logsdon says, whereas today, “we are leaders in space.”

Another stark contrast between Pence and Kennedy is their tone toward collaboration. Artemis is about “ensuring that the next man and the first woman on the Moon will both be American astronauts,” Pence said. He said something very similar in March at the National Space Council meeting where he set the 2024 deadline for landing a crew on the moon, where he emphasized these American astronauts will be “launched by American rockets, from American soil.”

By contrast, as Apollo unfolded, Kennedy left open the possibility of a “joint expedition to the moon,” adding in the 1963 address to the United Nations that “there is room for new cooperation, for further joint efforts in the regulation and exploration of space.”

“Surely we should explore whether the scientists and astronauts of our two countries – indeed of all the world –cannot work together in the conquest of space, sending someday in this decade to the moon not the representatives of a single nation, but the representatives of all of our countries,” Kennedy said.

NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine regularly touts a collaborative approach. Hours after Pence’s speech, Bridenstine appeared on a panel with other agency heads and praised their involvement in Artemis.

“We need international partners. We can do more when we work together than any one of us can do alone,” he said, even leaving open the possibility that astronauts from other countries could work “side by side on the moon” with NASA astronauts after 2024.

Pence’s America-first rhetoric does not seem to be discouraging partnerships. The European Space Agency is providing the service module for NASA’s Orion crew capsule, and the Canadian and Japanese space agencies have pledged upgrades to the Lunar Gateway, NASA’s planned reusable space station in orbit around the moon.

Also on the scene:

• In his remarks, U.S. Vice President Mike Pence pledged that the United States “will use all available legal and diplomatic means to create a stable and orderly space environment that drives opportunity, creates prosperity, and ensures our security on Earth and in the vast expanse of space.”

• Reporters asked NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine to go more in depth on international collaborations for Artemis. Bridenstine said he didn’t know when some of the pledges from other agencies would turn into formal, binding agreements, largely because each agency needs approval from its government before getting the funding. “It’s kind of like a jigsaw puzzle,” he said. “It takes some time to put it together, but all the pieces will come together. We just have to continue to work on it.”

• European Space Agency Director General Jan Woerner jumped to answer an audience question during Monday’s panel about how he would justify funding space exploration amid growing concerns about climate change from young activists like Sweden’s Greta Thunberg. He cited studies of Venus that helped identify the greenhouse gas effect. “This shows already that climate change has a direct link to exploration,” he said. “Space is helping Greta.”

About cat hofacker

As acting editor-in-chief, Cat guides our coverage, keeps production of the print magazine on schedule and edits all articles. She became associate editor in 2021 after two years as our staff reporter. Cat joined us in 2019 after covering the 2018 congressional midterm elections as an intern for USA Today.

Related Posts

Stay Up to Date

Submit your email address to receive the latest industry and Aerospace America news.