Stay Up to Date

Submit your email address to receive the latest industry and Aerospace America news.

Get competitors going on multiple lander designs and learn lessons from Commercial Crew

If U.S. astronauts land on the surface of the moon in 2024 as NASA plans, historians might someday cite a series of bold decisions in 2019 by managers at NASA Headquarters and Marshall Space Flight Center in Alabama.

I met with one of the decision-makers, veteran NASA engineer Lisa Watson-Morgan, in her office at Marshall on Aug. 30 to discuss these decisions and the strategy underlying them.

Watson-Morgan is program manager for the Human Landing System, or HLS, effort, in which contractors will vie to supply the lander for Artemis, as the 2024 mission is called. NASA assigned Marshall responsibility for the billion-dollar lander program in August, to the dismay of lawmakers in Texas, home to Johnson Space Center.

Getting astronauts to the moon in just five years will require combining “the speed at which we have seen some commercial partners operate” with “the lessons learned from NASA” in decades of human spaceflight, Watson-Morgan says. This way, “we all have a better chance of making the schedule,” she says.

In keeping with this strategy, NASA has been receiving regular feedback from prospective competitors about the language of the broad agency announcement it is drafting to start the HLS competition later this year. Three finalists will be selected by December and one lander will be chosen for the 2024 mission.

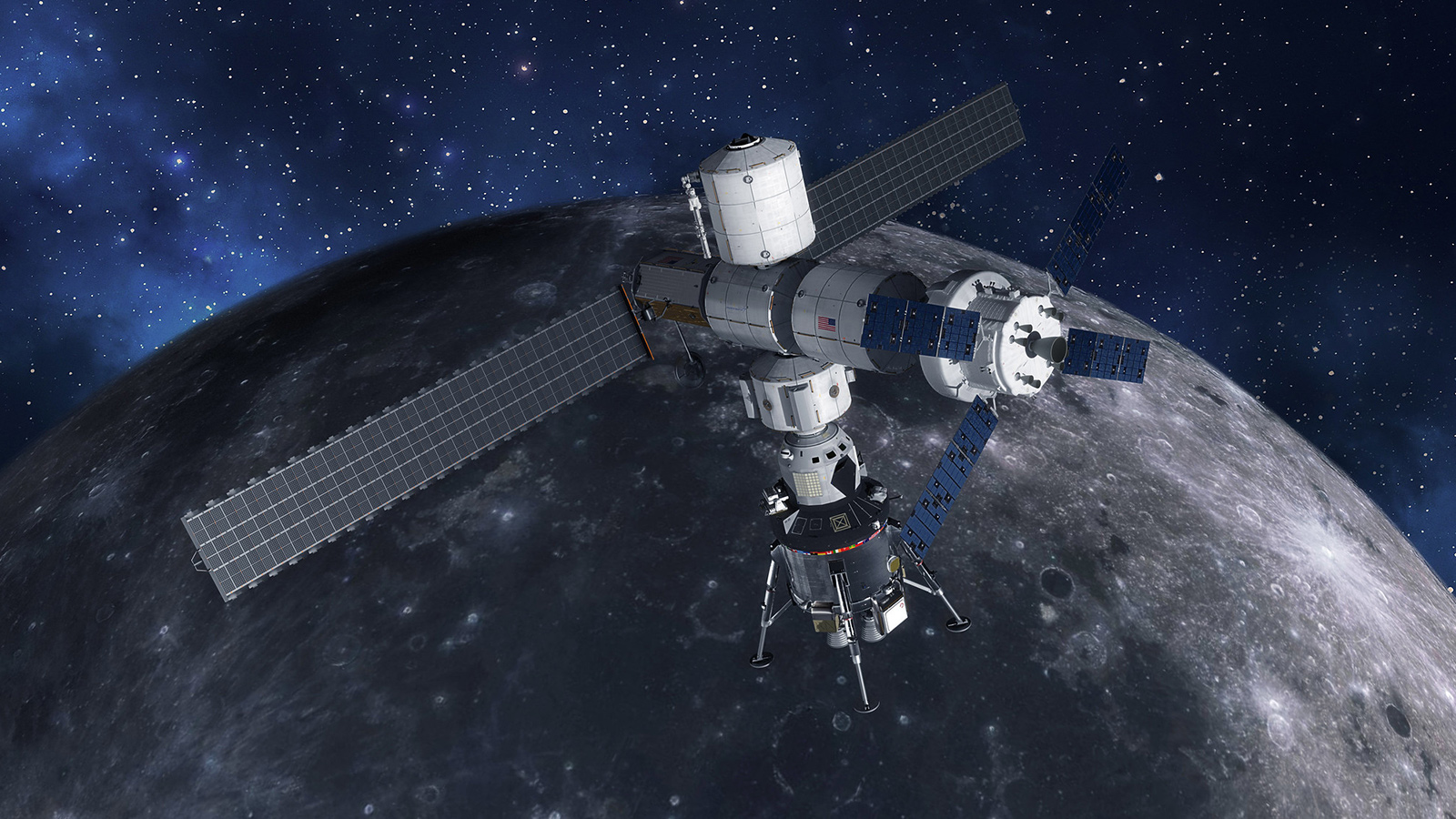

In July, NASA shifted gears and decided to emphasize the need for contractors to develop a fully capable lander rather than focusing on specific components. The agency removed all mention of a three-stage lander in its updated draft solicitation, released Aug. 30. Until then, NASA had specified one stage to transport astronauts to low lunar orbit from a planned lunar Gateway space station; a descent stage to carry them from low lunar orbit to the surface; and an ascent stage to boost them back to the Gateway. The new language asks for an “Integrated Lander [that] combines the envisioned capabilities of the Descent, Transfer Vehicle, and Ascent Elements.”

The three-stage lander is now “just a reference” for companies working on their own HLS proposals, Watson-Morgan says.

She was concerned that contractors might decide to give NASA what they think the agency wants, rather than submitting fresh ideas.

“I’m looking for the most innovative way that we can safely” land on the moon and return to the Gateway, Watson-Morgan says. “So whatever is that right balance of something that we have enough confidence in and that is definitely doable.”

Watson-Morgan says the only “hard set” requirement is that all proposed landers must be able to dock with the lunar Gateway. As things stand, the Gateway is a bit farther along than the landers. NASA in May hired Maxar Technologies of Colorado to build the Gateway’s power and propulsion element, and Northrop Grumman was selected in July to construct the Gateway’s habitat module.

Contractors have until Sept. 6 to comment on the updated lunar lander draft.

The HLS strategy draws inspiration but also lessons from the Commercial Crew program. Boeing and SpaceX have struggled mightily to ready their crew capsules to ferry astronauts to the International Space Station. The program is nearly two years behind schedule, and that is a disappointment that NASA knows it cannot repeat with Artemis.

So, instead of two spacecraft, as in the Commercial Crew program, three landers will be chosen under the lander strategy the agency began discussing in July. NASA would count on two of those to be ready for the 2024 landing, and then would choose one to carry out the mission. The remaining two landers eventually could carry astronauts to the moon as well.

Can NASA afford three landers? That’s an unsettled question. The longer NASA can carry all the lander proposals through development, Watson-Morgan says, “I’m game to do it, but that will really just be determined by money.”

NASA also will be more hands-on during HLS design and manufacturing compared to Commercial Crew. Fifty NASA employees will work on each lander in tandem with the company engineers.

“That is an approach that we’re using to try to mitigate some of the potential risk of having a full commercial-run design development type program,” Watson-Morgan says.

There is also the question of how to get the 2024 lander to the Gateway, so the landing crew can enter it for the trip to the surface. NASA has decided to give contractors latitude here as well. The draft announcement invites competitors to “propose a commercial launch vehicle approach” in which the HLS could be transported to space and to the Gateway in one piece or as separate parts. The lander would be delivered to the Gateway without a crew, since the astronauts will have arrived in an Orion capsule launched on a NASA Space Launch System rocket.

This approach would be distinct from the Apollo missions in which each crew and their spacecraft were launched on a single Saturn V.

Of course, another factor popped up in our conversation again and again: funding. Congress has yet to approve any of the $1.6 billion NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine has referred to as “down payment” on the Artemis 2024 landing.

About cat hofacker

Cat helps guide our coverage and keeps production of the print magazine on schedule. She became associate editor in 2021 after two years as our staff reporter. Cat joined us in 2019 after covering the 2018 congressional midterm elections as an intern for USA Today.

Related Posts

Stay Up to Date

Submit your email address to receive the latest industry and Aerospace America news.