Stay Up to Date

Submit your email address to receive the latest industry and Aerospace America news.

A weather-data transformation is playing out in cockpits

Getting a clear picture of the weather ahead of a flight can be more complicated than it sounds.

For starters, there is turbulence, the chaotic changes in air pressure and flow that can stress out nervous passengers and in rare cases injure them. Flight attendants are especially vulnerable, because they are often last to strap on their seat belts.

Then there are lightning strikes. Even if a lightning strike is merely suspected, the plane must be inspected on the ground, and that equates to costly downtime.

And of course weather has contributed to deadly air accidents. There was the 2009 crash of Air France Flight 447 off Brazil, in which ice is thought to have blocked the plane’s speed-sensing pitot tubes triggering a series of deadly missteps. In 2014, the pilots of AirAsia Flight 8501 lost control while attempting to climb over a storm.

Beyond safety, there are economics to consider. Relatively few passengers are injured by turbulence each year (44 in 2016, according to the FAA), but when injuries do occur, the medical expenses, lost income and legal costs rack up quickly. Also, wind direction and speed affect flight time and fuel burn. Making sharp turns at the last moment to avoid a storm might pose no safety risks but impose big fuel penalties.

What all these factors add up to is a strong impetus to deliver richer and timelier weather information to the cockpit, and that’s exactly what’s happening. It’s a revolution fueled by the convergence of broadband satellite communications with the advent of online apps and wireless tablet devices. New players and some established ones are rushing into this market with innovations.

The Atlanta-based Weather Company, for instance, says about 85 percent of U.S. major airlines and 40 percent of the top global airlines subscribe to its services to operate more than 50,000 flights per day. Customers receive weather forecasts, updated every 15 minutes, plus real-time weather data. Dispatchers plan flights with the data and pilots sometimes adjust their routes and altitudes based on it.

As recently as a couple of years ago, matters worked entirely differently. Pilots usually received weather information during preflight briefings and carried the paperwork aboard in their flight bags. During the flight, pilots would review these documents and view displays showing turbulence detected by onboard weather radar mounted on their aircraft’s nose or wing. These turbulence readings were limited in range and the types of disturbances they could detect. The pilots would typically request updates from air traffic controllers about turbulence and other weather.

Making the revolution possible

Two changes are empowering pilots to supplement or even replace those traditional sources of weather information.

Pilots now carry tablet computers aboard, and these mobile devices are known as electronic flight bags, or EFBs. Because they are unattached to the aircraft, they do not need certification, and neither do the purely advisory weather services that pilots tap into via these tablets. Without the need to certify, software developers can invent and upgrade better weather services quickly and economically.

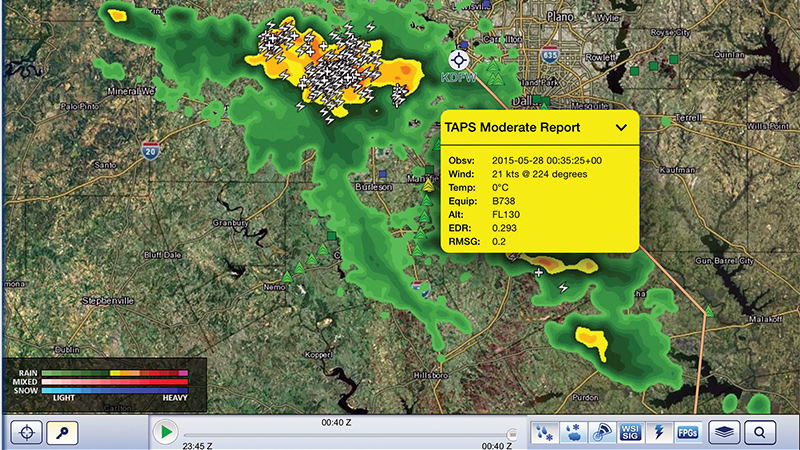

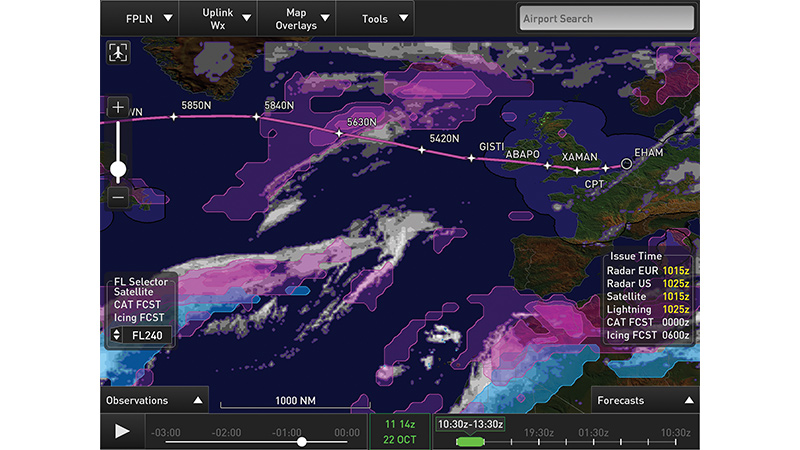

Improvements in airliner connectivity have also been made. Data can be sent quicker and more economically over internet broadband links. Honeywell’s Weather Information Service, now live with several airlines, gives pilots weather data via radio or satellite broadband, explains Flight Services Director Kiah Erlich. The latest forecasts are displayed on their EFBs, as is near-real-time weather from meteorological agencies such as NOAA and the United Kingdom’s Met Office. Different colors depict areas of icing danger, clear-air turbulence and cloud tops, and overhead and vertical views of difficult weather.

Crowdsourcing

Honeywell and the Weather Company are among those pioneering a technique in which weather data gathered by leading planes is shared with those following behind them.

This crowdsourcing method fills data gaps on difficult routes. Doppler radars, for instance, depict precipitation, but because these radars are projected from the ground at an angle, their coverage doesn’t extend far out over the oceans. Plus, Doppler radar coverage is limited in countries, including Mexico, and the data is confidential in China. NOAA’s weather satellites observe weather patterns over oceans and foreign countries, but those images and data are meant for forecasters and do not by themselves show enough details to help pilots.

So for these kinds of routes, Honeywell’s Weather Information Service displays crowdsourced data on EFBs.

The Weather Company crowdsources information too through an automatic turbulence reporting system. Product Director J.P. Gorsky estimates that this service offers the average large global carrier savings of $720,000 per year, for example, by avoiding turbulence that can injure passengers or crew. All told, he adds, costs can be reduced by $5 million a year through fewer cancellations, better customer loyalty due to improved flight experience and less preflight reporting time for pilots.

Multiple weather sources

With so much weather data and so many services emerging, one company, SITAOnAir, the Switzerland-based connectivity arm of aviation software firm SITA, has devised a service to sort it all out for customers.

Its Weather Awareness Solution offers pilots weather data from multiple providers, including Meteo France, the French government’s meteorological service; France-based Schneider Electric, whose services include automated weather assessments; and the Weather Company. The SITAOnAir service can anticipate and redraw alternative flight plans, further reducing crew workload, explains Toby Tucker, innovation director for SITAOnAir. Results can be displayed on iPads, iPhones and Windows devices. Data is sent by radio or broadband connection over an Aircraft Interface Device or by connecting the pilot’s electronic flight bag to cabin broadband. Customers download the application and subscribe to the service.

Approximately 20 airlines are either using or testing the Weather Awareness Solution, and about 4,000 pilots use it. The firm has added wind and temperature information for each flight level, plus the tropopause, the often turbulent boundary between the lower atmosphere and the more stable stratosphere. It also shows the isotherm for minus-70 degrees Celsius, the point where fuel icing is a concern. And the display gives information on airport headwinds, crosswinds, lightning and low ceilings.

Tucker says pilots like the ability to choose among weather providers. The service also allows pilots to share weather information if their employers agree.

Avoiding bad weather

Some vendors are adding weather to other information they provide pilots.

One of them is Germany-based Lufthansa Systems. It is preparing to overlay phenomena, such as turbulence, thunderstorms and volcanic-ash clouds, onto its pilot-charting application for EFBs. “Depiction of weather phenomena can be switched on or off and pilots can see relevant weather, flight plan and own-ship position,” explains product manager Ingo Ludwig. “Pilots will not have to switch applications to use it.”

Pilots can see Lufthansa’s weather displays on Windows or iOS EFBs with internet connections.

Ludwig expects the main benefit to be saving time and fuel by circumnavigating bad weather earlier than is possible with onboard radar. He, too, sees gains in passenger comfort and lower maintenance costs by avoiding severe turbulence.

Lufthansa plans to deliver the new weather capability by the end of 2017 and expects most of the 80 airlines that use its pilot-charting application to adopt it.

Meanwhile, North Carolina startup WxOps has been working with Hawaiian Airlines to give pilots and dispatchers what chief operating officer Al Peterlin calls “a common operating environment” of data. This includes weather data, logistics, flight manuals, ground operations and text messages affecting flight safety and efficiency. Its software operates over broadband connectivity and will eventually work on Windows and other EFBs.

The WxOps application will include its own predictions of clear air turbulence and will offer pilots weather data from NOAA and private providers. The service has been tested on Hawaiian’s Boeing 767s and will soon be tested on the carrier’s Airbus A330s. WxOps will offer it to other airlines as well. So there will be plenty of high-tech competition in this rapidly evolving weather front.

EFFICIENCY

Honeywell is testing software that could improve flight management by advising pilots of the optimum altitude to save time and fuel, based on the latest wind speed and direction.

Related Posts

Stay Up to Date

Submit your email address to receive the latest industry and Aerospace America news.