Stay Up to Date

Submit your email address to receive the latest industry and Aerospace America news.

Last year’s fatal midair collision outside Washington, D.C., and 43-day government shutdown put a spotlight on the strained U.S. air traffic control system. As the Department of Transportation and FAA proceed with plans to grow the workforce and overhaul equipment, Charlotte Ryan explores what brought ATC to this point and the challenges ahead.

On a cold January evening at Washington’s Reagan National Airport, an air traffic controller’s voice cut through the noise of a conflict alert: “PAT two-five, do you have that C-R-J in sight?”

The controller was speaking to the three U.S. Army personnel aboard a Black Hawk helicopter, flying near the airport for a routine training flight. Seconds later, as the rapid beeping in the background continued, the controller directed, “PAT two-five, pass behind that C-R-J.”

The helicopter pilot requested to keep visual separation from the incoming Bombardier CRJ700 jet, or monitor it manually, which the controller granted.

Inside the Black Hawk, the Army instructor asked the pilot to “Come left for me, ma’am,” an apparent attempt to steer clear of the jet. Seconds later, the beeping accelerated, and the controller heard a surprised reaction from the jet.

Then silence.

These were the final moments before the collision near Washington, D.C., that sent both craft plunging into the Potomac River, killing all 67 aboard. It was the first major commercial plane crash in the U.S. since 2009, and the deadliest since 2001.

The National Transportation Safety Board’s final report of the accident is expected in January. The preliminary report published last March and public meetings held throughout 2025 indicate that among the contributing factors was a controller staff stretched too thin to manage the airport’s traffic. Specifically, air traffic controllers told investigators that their pleas to reduce traffic, change a route that put helicopters into the path of aircraft and have more staff assigned to the tower had all been ignored.

It was a tragic illustration of what industry groups and experts have been warning for years: The U.S. air traffic control system is overstretched and understaffed, to the point that minor equipment glitches or weather disruptions can cascade into major delays or even safety risks.

The Potomac crash “is an example that the aviation system as a whole failed that evening, and we owe the families and friends of those victims our best effort to make sure the system is better, safer and stronger,” says Tim Arel, the former head of FAA’s Air Traffic Organization, in an interview. He took a buyout offered by the Trump administration in April, capping a nearly 40-year career at FAA.

Since the January collision, FAA has made a number of changes aimed at making operations around Reagan Airport safer, an FAA spokesman told me in an emailed statement. These include eliminating the use of visual separation within 5 miles of the airport and increased support, oversight and staffing.

“Safety remains the FAA’s highest priority,” the spokesman said. “We are closely supporting the NTSB-led investigation, and we will quickly take any necessary actions and conduct appropriate reviews based on the evidence.”

Even in non-fatal incidents, controllers are reporting challenges with equipment and operations, according to my review of controller reports of 2025 incidents at busy airports, published in a NASA safety database. Communication failure is “a grave threat to safe operations” at Newark Liberty International Airport, reads one report, which goes on to warn that “a midair collision is imminent.” Another report out of Atlanta calls for authorities to “fix the frequencies before something bad happens.” A third from Fort Worth, Texas, reads that the airspace around the airport is “so out of control, so unsafe” due to aircraft that fly using visual navigation.

“In light of DCA, it is disgusting that this is still Class E airspace,” the Fort Worth controller wrote, referring to the Potomac crash. Helicopters and other aircraft that operate under Visual Flight Rules aren’t required to be in contact with ATC as they approach, making it potentially trickier for controllers to manage traffic.

Several reports mention controllers juggling training and directing aircraft, and others mention problems with transmission.

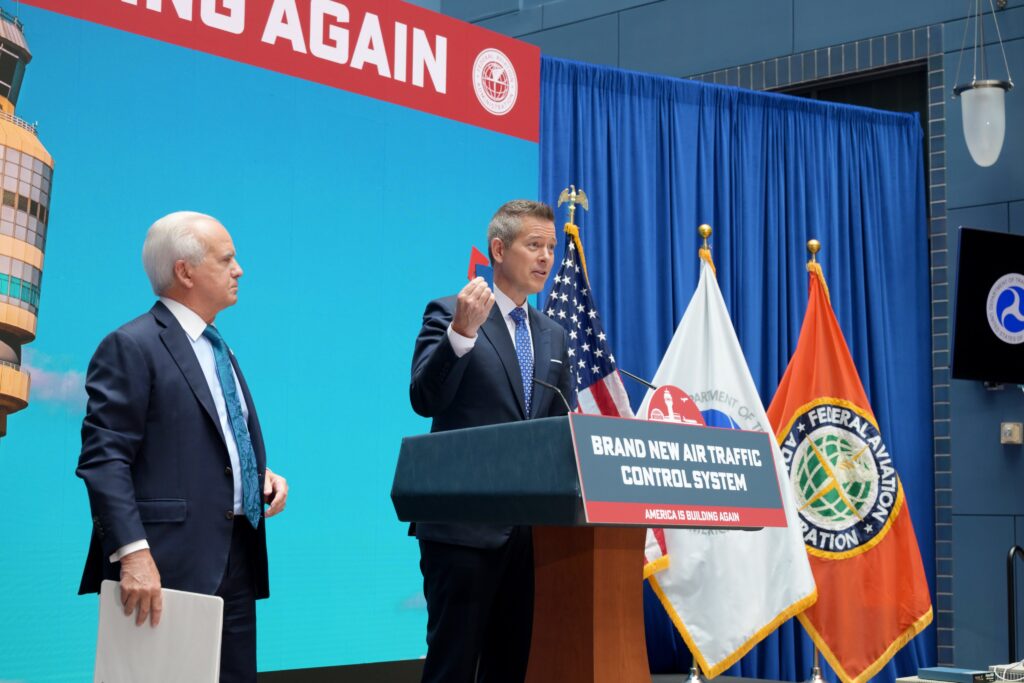

Amid mounting pressure for FAA to address all of these issues, Transportation Secretary Sean Duffy in May laid out a plan to overhaul ATC, and in early December announced that Virginia-based contractor Peraton would serve as “prime integrator” of the rollout. The initiative is to be partially funded by $12.5 billion included in President Donald Trump’s signature legislative package.

“The system we have here is not worth saving,” Duffy said in May. “I don’t need to preserve any of this; it’s too old.”

Increase hiring

Central to any plan to address air traffic woes is hiring more controllers.

“We haven’t had enough air traffic controllers in America for a very long time,” Duffy said in the aftermath of the DCA crash. “They are stressed out. They’re tapped out. They’re overworked. That’s no excuse. It’s just a reality of what we have in the system.”

Today, there’s a shortage of about 3,800 controllers, according to NATCA, the National Air Traffic Controllers Association. Such shortages date back to 1981, when President Ronald Reagan fired some 11,000 controllers in one fell swoop after they refused to return to work from a strike.

FAA hired thousands of controllers in the following years, but many of them are now reaching retirement age. The total workforce for fiscal 2024 was 14,264 air traffic controllers, and 6,872 are projected to depart through 2028, according to FAA’s workforce plan published in August.

To offset this, the agency plans to hire “at least 8,900 new air traffic controllers through 2028,” the report reads, but hurdles remain there as well. There’s a stubbornly high dropout rate during training — overall failure rates reached 26% in 2024, with even higher rates at more congested facilities.

According to former controller Rob Mark, who now runs the aviation blog Jetwhine, it’s a demanding job. The long hours are “a killer,” and not everyone can handle the pressure involved in directing traffic in busy airspace.

The rigid hierarchy and red tape can also prove challenging.

“It’s still very much bureaucratic, and I don’t think a bureaucracy works very well in this kind of a dynamic industry,” he says. “I don’t know that it ever did, and I think that’s another reason it’s never really gotten any better.”

According to NATCA, 41% of controllers work 10 hours a day, six days a week. A June report from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine, “The Air Traffic Controller Workforce Imperative,” expressed concern that these staffing levels could cause fatigue and affect safety, either because controllers are working too many hours or because having fewer controllers results in a single controller working a combined position, when having assistance would be safer.

One of the 2025 incidents in the NASA database features such a scenario, where a controller reported failing to catch that an aircraft was coming in too low. The controller had been on position for at least two hours and was handling training as well as directing traffic.

“I feel that in the future controllers should be on position less than 2 hours, especially when training is involved,” the controller wrote in the report.

In addition to juggling these tasks, controllers face tough shift patterns, such as the 2-2-1 or “rattler” shift. This schedule involves starting at 1:30 p.m. for two days, moving to a 7 a.m. start for the next two days, and then returning at 11 p.m. on the fourth day, with only eight hours off between the day and night shifts. This means a shorter work week and more time off after, but it also disrupts sleep patterns and can result in controllers getting as little as three hours of sleep between shifts, according to multiple FAA surveys. NATCA told me it is conducting a national review of the schedule with FAA to evaluate fatigue impacts.

Although hiring more controllers is an obvious solution, FAA has long struggled with recruitment. It’s a well-paid job — with a median salary of around $145,000 as of May 2024, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics — but it also requires a very particular skill set. Perhaps most importantly, controllers must be able to stay calm and solve problems in a three-dimensional space. This is hard to screen for in aptitude tests, and the pressure means plenty who initially sign up later walk away.

“When I was training at my first facility, there were times that I didn’t think I was going to make it, because it was really hard — and I’d done this before,” says Mark, who was an air traffic controller in the U.S. Air Force before spending a decade working in the tower and as an FAA supervisor. “Life is a challenge, and some people cope with it better than others.”

Hoping to provide additional incentives, Duffy in May announced a plan to implement a 30% salary increase for new controllers, as well as a $5,000 bonus for those who graduate from the academy. He also is allocating extra resources to boost exam pass rates. To retain existing staff, the agency struck a deal with NATCA for incentives to encourage senior controllers to stay on for longer, rather than take early retirement, and to transfer to short-staffed facilities.

The FAA spokesman said the agency hired 2,026 new controllers as of September, meeting its 2025 hiring goal. The agency has also attempted to streamline the hiring process in various ways, he said, including working with qualified institutes to get recruits on the job faster and enhancing training through the use of simulators.

Updating training and towers

Not only is it hard to find the right people, it’s also becoming more difficult to train them. FAA has long been challenged to attract enough former controllers to serve as trainers — a job that’s sometimes part time and usually requires spending part of the year in Oklahoma City, the main facility where instruction takes place.

FAA took steps to address this in late 2024 by allowing recruits to complete the first stage of training at eight other centers around the country, including Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University’s Daytona Beach campus in Florida.

Once training is complete, new controllers are often sent off to aging towers, many of which are equipped with outdated technology and faulty wiring. FAA said in May the risk posed by these old buildings is greater than ever, highlighting failing infrastructure like HVAC systems, pest issues, leaking roofs and asbestos hazards. On a June visit to the San Diego tower, Duffy described how controllers had to jerry-rig the blinds to shade themselves from the hot California sun.

Part of the renovation challenge, notes Arel, is the vastness of the system — 406 towers across the country. That means upgrades often happen in small chunks, rather than in large swoops like what Duffy has proposed.

The system “has been modernized in increments when it can be afforded,” says Arel, who spoke to me in October amid the government shutdown. That 43-day closure created an additional challenge, he says, because while controllers had to keep reporting to work, maintenance and renovation projects were halted.

“Things like shutdowns that are happening right now have stopped us incrementally as you start working on something.”

As for the technology inside the towers, many of the 2025 reports referenced the continued reliance on paper, floppy disks and Windows 95. That matches up with the experience of Elaine Chao, who served as deputy transportation secretary for two years under former President George H.W. Bush and then in the department’s top job during the first Trump administration. Little changed in the intervening two and a half decades, she says, recalling young recruits accustomed to iPhones having to use paper strips to track flights for landing and takeoff.

“We cannot continue to operate with a system that does not upgrade and modernize itself on a timely basis,” she says. “Right now, it’s still safe due to the tremendous skills of the men and women who run the air traffic control, but what happens when more and more of them begin to retire?”

The union Professional Aviation Safety Specialists, or PASS, which represents the technicians who maintain air traffic control equipment, says the problem is not just the aging equipment, but the challenges associated with acquiring replacement parts. Technicians are left trying to track down obsolete equipment, or even spare parts from a contractor that has gone out of business.

PASS President Dave Spero likened the strategy behind ongoing upgrades to “spreading the peanut butter a little thinner.” Funding shortfalls have meant that rather than implementing a coherent system across the country at every facility, upgrades have been made in a patchwork fashion. This means there are multiple versions of various technologies, from voice switches to radars to automation and instrument landing systems. The impacts of this echo throughout the wider system, requiring extra training for technicians and controllers, extra classrooms and extra parts for maintenance.

“It’s a bit like a car, if you keep running it,” says Mark, the former controller. “At some point, if you’re not really getting into the guts, it finally says ‘I’m dead,’ and it just won’t work anymore. The stuff is just so old, and the process we have over here to bring in new equipment is so antiquated that it’s kind of a perfect storm.”

The way forward

Duffy’s plan calls for building six new air traffic control centers and 15 towers with TRACONS (Terminal Radar Approach Control Facilities), as well as replacing aging infrastructure with new fiber, wireless and satellite technologies. Runway safety is also to be improved by bringing surface technology to more aircraft to enable real-time tracking of aircraft and ground vehicles.

The agency has set a 2028 target to achieve all this, and Duffy has vowed to move “at the speed of Trump.” But that might be easier said than done. The famously bureaucratic agency has previously taken up to seven years to get new equipment, Chao recalls.

Spero of PASS shared similar experiences, adding: “If you’re planning on doing it the way we’ve always done it, then that timeline is not realistic at all in any way, shape or form.”

The government shutdown was the latest speed bump. Many federal workers did not receive paychecks between mid-October and early November. Media reports described air traffic controllers turning to second jobs or calling out sick, increasing the risk of delays and safety issues due to shortstaffing.

“The weight of being distracted, whether they’re working another job or they’re only working their FAA job, but not receiving enough income to cover their normal operating cost, that’s something that we know weighs on individuals,” says Arel. “Distractions aren’t good in any safety-related profession.”

Since 2005, lapses and reductions in funding associated with repeated shutdowns have had a negative impact on the air traffic control system, says Paul Rinaldi, head of operations and safety for the trade association Airlines for America. It’s too soon to quantify the specific impacts of the 2025 shutdown, he says, but “the realistic view is it will interrupt all of the progress we’re trying to make to make the system safer and more efficient.”

So, where does the U.S. go from here? In Chao’s view, it might be time to revisit the idea of privatizing the system, though she is loath to use that word. She tried to get a plan through Congress in 2017 that would have spun air traffic control out of the federal government and into a not-for-profit partly funded by the Aviation Trust Fund. The bill passed the House Transportation Committee but was never put up for a floor vote, and no similar proposals have been introduced in the years since.

“We’ve worked in this field for decades, and we’ve tried putting Band-Aids on it,” she says. “We’ve tried to improve the procurement process. None of that seems to have worked.”

About Charlotte Ryan

A London-based freelance journalist, Charlotte previously covered the aerospace industry for Bloomberg News.

Related Posts

Stay Up to Date

Submit your email address to receive the latest industry and Aerospace America news.