Stay Up to Date

Submit your email address to receive the latest industry and Aerospace America news.

If all goes as NASA plans, the deorbiting of the International Space Station in early 2031 will be its final chapter, but also the start of a new one in which one or more companies will operate their own stations independently from NASA. But not everyone believes the station should be deorbited then, if ever. Jonathan O’Callaghan examined the differing views and proposed alternatives.

Editor’s note: This story has been updated to correct the title of Ron Lopez, president of Astroscale U.S., and to clarify the company’s role in a 2022 white paper that proposed recycling material from the International Space Station.

Gary Calnan traveled to the White House in 2022 with a proposal to melt parts of the International Space Station down into rocket fuel. His firm, CisLunar Industries of Colorado, was developing technology to recycle and reuse machinery in orbit, and the National Space Council and the Office of Science, Technology and Policy were interested to hear more.

The company had previously published a white paper with several other companies — including Astroscale U.S., the Denver subsidiary of the Japan-based on-orbit-servicing company — describing how radiators, solar panels and batteries could be reused and how other parts of the station could be turned into an orbital salvage yard. For example, CisLunar was developing technology in partnership with the Australian company Neumann Space that could melt metal structures in orbit into rods of aluminum that could serve as fuel for electric propulsion, a concept that the U.S. Space Force awarded Cislunar a $1.7 million contract last year to explore.

That’s just one idea for what could be done with ISS instead of steering it into the atmosphere to break apart and largely burn up over the Pacific Ocean in early 2031.

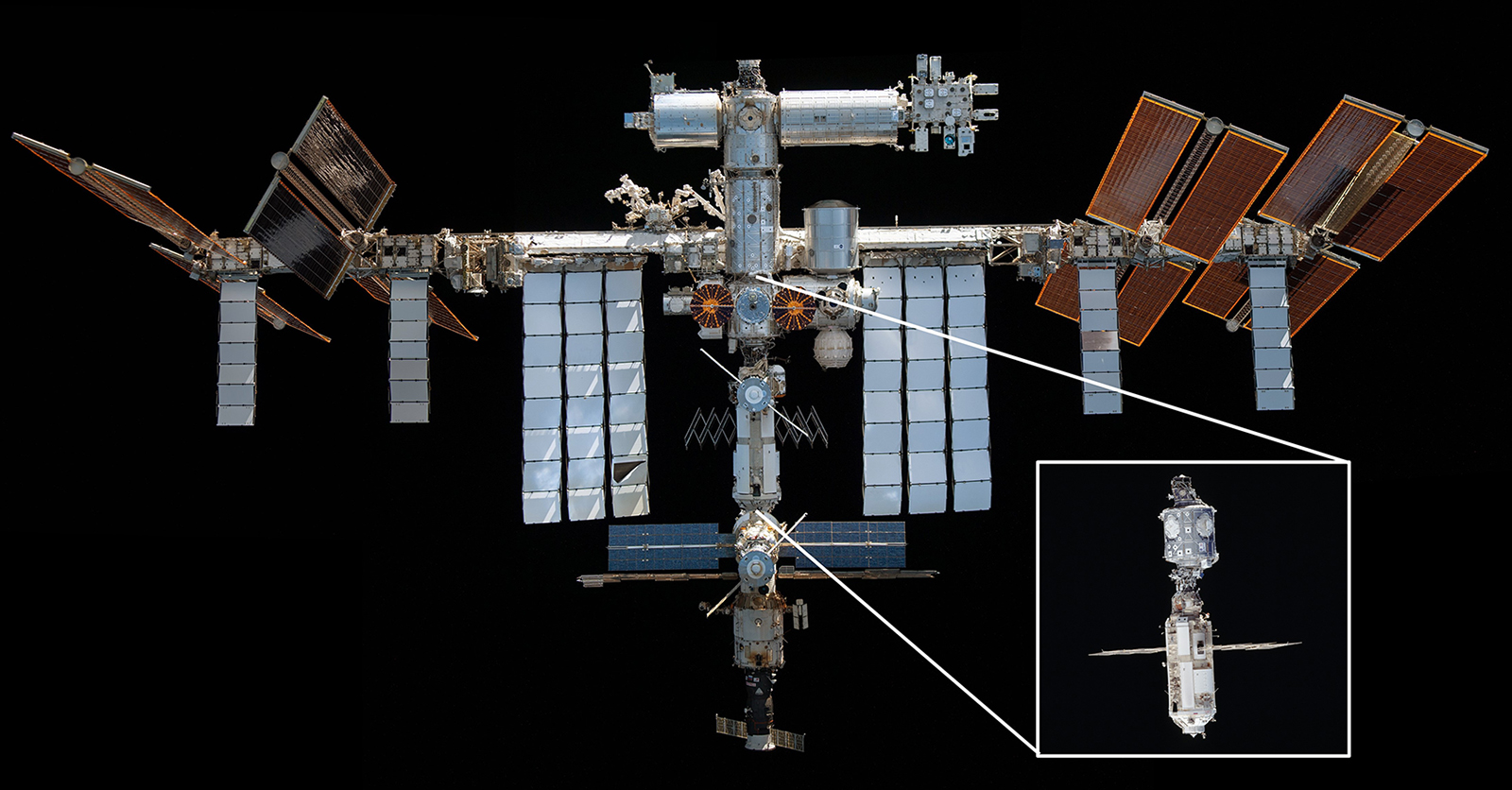

While NASA has in the past slipped disposal dates for ISS to the right, the 2031 date has sparked former astronauts and technologists, including AIAA members, to discuss the wisdom of the plan among themselves — and in some cases publicly. That’s because in June, NASA awarded an $843 million contract to SpaceX to create the U.S. Deorbit Vehicle, a larger version of the Cargo Dragon.

The selection of the USDV “makes it more real,” says former NASA official Daniel Dumbacher, who last month completed nearly six years as executive director and then CEO of AIAA.

An additional trunk section would be added to a Dragon and packed with fuel and 30 Draco engines.These thrusters arrayed around the base of the trunk would fire with 10,000 Newtons of thrust — about four times the thrust of a normal Dragon — to slow the 420-metric-ton station and steer it into the atmosphere toward a region of the Pacific Ocean yet to be chosen. To NASA, that scenario is vastly preferred over one in which atmospheric drag gradually pulls ISS lower and lower until the station begins to tumble uncontrollably — increasing the odds of any surviving components raining down on populated areas.

Among those with thoughts on the matter is former astronaut Tom Jones, who was a member of the space shuttle crew that delivered ISS’ Destiny module to orbit in 2001 and conducted three spacewalks to help install it. “I would not like to see it dumped in the ocean,” says Jones. “I would spend the same money on boosting it to a high orbit,” one where it would remain for “decades if not centuries” and be used as a future resource, such as for its aluminum. He reiterated this suggestion in a June keynote at the Outer Space Heritage Summit, hosted by AIAA and the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum.

Despite such qualms about the fate of the $150 billion station, NASA has shown no signs of rethinking matters. In a deorbit summary published in June, the agency said it had considered alternatives for the station but found none were viable. “NASA has concluded that deorbiting the International Space Station using a U.S.-developed deorbit vehicle, with a final target in a remote part of the ocean, is the best option for station’s end of life,” the agency wrote.

That decision, according to NASA, was driven in large part by the age of the hardware that arrived in a series of assembly missions between 1998 and 2011. “The primary structure of the station, such as the crewed modules and the truss structures, cannot be repaired or replaced practically,” the agency wrote in the summary, noting there was an “original 30-year structural life estimate” for these components, which is now being reached.

Andy Thomas, who holds a Ph.D. in fluid mechanics and is a former NASA shuttle astronaut who flew ISS assembly missions in 2001 and 2005, agrees that age is an issue that would need to be addressed if station weren’t deorbited. “There would be engineering limitations on some of the ISS systems and hardware,” he says. “Critical systems are reaching end of life. I suspect the biggest challenge would be maintaining the overall structural integrity of the station for many more years.”

Some are sanguine about deorbiting the station, not only because of the age of the components, but also because doing so would free up roughly $3 billion a year for other human spaceflight projects, such as NASA’s return to the moon.

“It hurts me to say it needs to come down,” says Wendy Whitman Cobb, a professor at the U.S. Air Force School of Advanced Air and Space Studies in Alabama. She notes similarities with the end of Russia’s Mir space station in 2001, when a Progress vehicle pushed the station’s orbit into Earth’s atmosphere. Russia was eager to continue Mir, but NASA “saw that it was taking Russia’s attention and funding” away from ISS, says Whitman Cobb.

“Probably we’re seeing echoes of that here,” she says. “Space is a harsh environment. I think there’s a lot of sentimentality, but at the end of the day, safety is going to trump sentimentality.”

And so, as Thomas says, “The clock is certainly running.”

Others have suggested boosting ISS upward into a graveyard orbit, where its orbit would take centuries to degrade and the station could be left uncrewed. Thomas investigated this possibility for NASA in 2014, examining whether solar electric propulsion could slowly but continuously boost the station higher.

“You could do it either with a single large unit or multiple smaller units,” he says. “I would favor the latter, as it gives you some redundancy in the event of engine failure. But there is no doubt that it would be an engineering challenge.”

Brent Sherwood, a former senior vice president of space systems at Blue Origin and now the Space Domain lead for AIAA, favors the idea of a graveyard orbit.

“A 200-year orbit buys lots of time for multiple generations of advanced spaceflight to decide if they want to deorbit it, boost it higher or salvage it,” he says. “[Deorbit] just seems hasty and premature. This ought to be a more transparent, hard conversation. Maybe the outcome is the same, but maybe it’s not.”

However, placing ISS in a parking orbit would still require considerable and continued legwork by NASA and the 14 other ISS partners. It also opens up the possibility of ISS becoming a significant debris risk, says Jonathan McDowell, a Harvard-Smithsonian Center astrophysicist in Massachusetts who monitors worldwide astronautical activity.

“If it gets into a tumbling mode, it could break up,” he says.

In the June deorbit summary, NASA said ISS operations “require a full-time crew to operate,” so it could not simply leave the station in a higher orbit uncrewed. It did note that raising the orbit to 800 kilometers or higher would give the station an orbital lifetime of at least 700 years. But reaching this altitude would be difficult and “require the development of new propulsive and tanker vehicles that do not currently exist.” SpaceX’s Starship could do the job, the agency said, but “there are prohibitive engineering challenges with docking such a large vehicle to the space station and being able to use its thrusters while remaining within space station structural margins.”

After ISS, NASA’s hope is that private companies will operate one or more stations in low-Earth orbit. One aspiring operator, Axiom Space of Houston, plans to attach up to four modules to ISS beginning in 2026, partially funded by NASA, which would later be detached to form a free-flying space station. If plans hold, at least one of these stations would be operational before 2031. But should they be delayed, ISS Program Manager Dana Weigel said in a July press conference about the deorbit plans that NASA may be willing to “extend ISS a little bit to avoid a gap in low-Earth orbit.”

Though she did not reference it, the U.S. had to rely on Russian Soyuz capsules to ferry astronauts to and from ISS during the nine-year gap between retirement of the space shuttles and the first Commercial Crew flight.

“We’d really like an overlap between station and the next platform,” Weigel said.

Even in that scenario, it’s unlikely that Axiom or other private companies would consider taking over the entire ISS if such an opportunity arose, says Courtney Stadd, a former NASA chief of staff. He says he has a “hard time trying to figure out where the private part of that partnership would see a generation of revenue” in a reasonable period.

“Maybe over time you get a sufficient number of space travelers, but how many years until you reach that critical mass?” he says. “I think the venture capital and investment people that I interact with would say there’s no business case to be made.”

Before Mir was deorbited, such a transition to the private sector was attempted by a privately funded initiative called MirCorp. Based out of the Netherlands, MirCorp hoped to take over operations of Mir from Russia, but the effort eventually failed due to a lack of funding.

“Privatizing a government laboratory in orbit is a very hard thing to do,” says Sherwood.

If ISS cannot be saved in its entirety, some have suggested saving smaller parts of it. Former astronaut Frank de Winne, the ISS coordinator for the European Space Agency, said the presence of the Axiom modules could help in that regard.

“If there are things we can reuse from ISS and transfer to the Axiom modules, certainly we are ready to look into that,” he says, but he noted that ESA had “not started concrete discussions” with Axiom on the topic. Axiom declined to comment on the possibility.

As for turning parts of ISS into rocket fuel, I could not learn whether the Cislunar white paper reached the NASA officials who are in charge of the station’s fate.

“We did not get any feedback,” says Ron Lopez, president of Astroscale U.S., one of the companies involved in the white paper.

In lieu of a viable alternative, that leaves the seemingly inescapable option of dropping ISS over the ocean.

“It’s a sad but probably inevitable milestone,” says Thomas, the former astronaut. “To say we spent $100 billion over the last 25 years and we’re going to dump it in the ocean is very sad, a final conclusion to what has been a pretty remarkable engineering achievement.”

But the clamor to save ISS may increase.

“I wouldn’t be surprised if there was a public outcry,” says Mai’a Cross, director of the Center for International Affairs and World Cultures at Northeastern University in Massachusetts, perhaps even to the point that government steps in.

“Congress can direct NASA to not deorbit,” says Michelle Hanlon, executive director of the Center for Air and Space Law at the University of Mississippi’s School of Law. That would require funding, but that could be repurposed from elsewhere, such as SpaceX’s USDV contract.

Bob Brumley, senior managing director at the technology development firm Marble Arch Partners in Virginia, suggests another alternative: taking the money NASA has earmarked for its planned lunar space station, Gateway.

“I’d take the billion dollars a year for Gateway and use that money to save ISS,” he says.

In that July press conference, I asked Ken Bowersox, head of NASA’s Space Operations Mission Directorate, if the fate of ISS was 100% certain.

“I’ve never seen anything that’s 100% in space,” he said. “It wouldn’t be surprising at all to me if, in a couple of years, folks came in and took a look again at the work that’s been done to try and decide what we would do at ISS end of life.” But, he added, “I honestly think they’ll end up in the same spot.”

About Jonathan O'Callaghan

Jonathan is a London-based space and science journalist covering commercial spaceflight, space exploration and astrophysics. A regular contributor to Scientific American and New Scientist, his work has also appeared in Forbes, The New York Times and Wired.

Related Posts

Stay Up to Date

Submit your email address to receive the latest industry and Aerospace America news.