Stay Up to Date

Submit your email address to receive the latest industry and Aerospace America news.

Companies developing Mach 5 passenger planes and capsules for on-orbit manufacturing could supply the Pentagon the extra hypersonic test platforms it has long been seeking. Keith Button spoke to some of the aspiring providers about applications and the status of their technologies.

The goal of Venus Aerospace’s May flight test was straightforward: Propel a small rocket with a subscale version of the rotating detonation rocket engine the Houston startup is developing for its planned Mach 9 passenger plane and other hypersonic craft. But an off-hand comment by an unidentified observer suggested another possible market:

“We literally had a customer who watched our flight and says, ‘Hey, on the next flight, could we talk about integrating something into this?’” says CEO Sassie Duggleby.

The interaction illustrates a potential opportunity for the U.S. Department of Defense to increase the number of hypersonic flight tests conducted each year from a handful to several dozen — and in doing so, finally have a shot at closing the technology gap with China and Russia.

Flight tests are the gold standard for proving hypersonic vehicles and components because it’s tough, if not nearly impossible, to simulate the extreme heat and violent forces that would be exerted on a wing surface or the electronics of an aircraft.

“You’ve got to think about all the sensors and the cameras and the materials and all the different pieces that go into an integrated system: Each one of those individual components needs to be tested in order to be integrated into a full-out system,” Duggleby says.

Wind tunnels might be fine for early tests on a prospective material for the exterior of a missile, for example, but not for proving the material will hold up during a Mach 5-plus flight, says Will Dickson, chief commercial officer at Colorado-based Canopy Aerospace.

“A lot of times they’ll claim Mach 6, Mach 7, Mach 8, Mach 9, but it’s just for 20 milliseconds. That’s just not really helpful,” says Dickson, whose company makes thermal protection materials for spacecraft and missiles. “Customers want to see the results of testing a material on an actual hypersonic flight. It’s not an area where customers want to take a ton of risk.”

Compounding the challenge is the very small number of flight test providers available today. Of the 500 or so hypersonic payloads that various customers want to test in the U.S. in 2025, only a handful will fly, according to Duggleby. And so, companies like Venus Aerospace that are developing craft for other high-speed flight applications have emerged as a potential solution: After all, the thinking goes, a hypersonic rocket test launch or a spacecraft designed to grow pharmaceutical crystals in orbit and then survive the searing conditions of atmospheric reentry could easily be adapted or repurposed to test components and materials for future hypersonic missiles.

The benefits aren’t only on the government side. For a startup like Venus Aerospace, which is planning a hypersonic flight test in 2026 of the engine for its proposed Mach 9 airliner, DOD-funded research offers the promise of a welcome influx of cash.

“We’re happy to have you come along for the ride and pay us for it. It’s a faster way for us to get to some revenue as we’re continuing to push things forward,” says Duggleby. “If we’re flying to learn more about our system, we might as well fly a payload for a customer and get paid for that.”

Ramping up

Until recently, the U.S. had conducted about one hypersonic flight test per year for about 20 years, says Iain Boyd, an aerospace professor at the University of Colorado. “That’s absolutely not enough to actually make real progress,” he says.

Over that same period, China is believed to have flown “multiples of 10” times the number of U.S. flights, he says. “It’s generally known that they’ve been flying and flying and flying and flying.”

Meanwhile, Russia has already begun fielding hypersonic missiles, firing air-launched Kinzhal missiles during its ongoing invasion of Ukraine.

“They’ve got deployed hypersonic weapons that the U.S. does not have yet, so regardless of what the test cadence is, they have managed to produce hypersonic weapons,” says Doug Crowe, senior vice president of program management for NSTXL, the National Security Technology Accelerator, a DOD-funded nonprofit that fosters technology development.

The U.S. has responded by funneling hundreds of millions of dollars annually toward flight test activities to develop technologies for hypersonic missiles and for defenses against them. For the 2025 budget year, the Pentagon requested $6.9 billion for hypersonics research overall, according to the Congressional Research Service, and $3.9 billion for fiscal 2026. So far, that flight test money has flowed to a range of test beds, from plummeting space capsules, to rockets originally designed for launching small satellites, to drones launched from jet planes in flight.

Late last year, the U.S., Australia and the U.K. signed an agreement to spend $252 million on joint hypersonic flight tests by 2028. In January, the Department of Defense’s Multi-Service Advanced Capability Hypersonics Test Bed program — better known as MACH-TB — awarded a five-year, $1.45 billion contract to Kratos Defense & Security Solutions, which will dole out the funding to other companies for flight tests. The sprawling reconciliation legislation that President Donald Trump signed into law in July includes $400 million for expanding MACH-TB and $2.7 billion for other hypersonic weapons programs, plus $24.4 billion to develop the proposed Golden Dome shield.

“There’s a lot of money pouring in; there’s a lot of technology pouring in,” says Brian Rogers, vice president of global launch services at Rocket Lab, a California-based rocket launcher and subcontractor on the Kratos contract. “The world of geopolitics [is] in such a place that missile warning, missile track, missile defense is an important thing, and (so is) the commercial market for aerospace and space.”

NSTXL has been helping attract potential subcontractors for MACH-TB, and Crowe says he expects the program will reach its goal of funding 50 hypersonic flights per year by 2027. With a flight every week or so, design cycles will shorten considerably.

“Right now, they do a design iteration; they may have to wait six months or more until they can actually get a flight test to validate it,” he says. “If they’ve got corrective actions, that goes online, so before you know it, you did two things and it’s taken you a year to get that done.”

Part of the reason why actual flights are so valuable is the lack of knowledge about the physics of flying at Mach 5 and above, says Zachary Krevor, CEO of Stratolaunch of Mojave, California. Another subcontractor on the Kratos contract, Stratolaunch, is in the process of building a fleet of reusable, air-launched testbeds that could eventually complete dozens of test flights per year for DOD and other customers. Temperatures on a hypersonic vehicle’s surfaces rise above 1,100 degrees Celsius as it pushes through the air, then the air begins to ionize around the vehicle.

“Your control surfaces are either not as effective or actually potentially changing,” Krevor says.

So far, Stratolaunch has conducted four flights with versions of its Talon-A autonomous aircraft, including two that reached hypersonic velocity.

Learning on the fly

Another advantage of actual flights is that testers can see how their tech responds to “stacking” conditions, says Dickson of Canopy. That means vibrations from the flight, plus bow shock waves at certain velocities, plus sustained heat and pressure for minutes at a time, plus variations of heat and pressure at different altitudes and speeds, plus how the technology interacts with radios or sensors.

As these flights produce data about hypersonic aerodynamics, that information can also be fed into computational models. As those models improve, it will open up new design possibilities for space vehicles, says Dave McFarland, vice president of hypersonic and reentry test for Varda Space Industries of El Segundo, California. The company began flying space capsules for on-orbit manufacturing and research in 2023.

While Varda’s main business model is focused on pharmaceutical customers and others that want to manufacture substances in microgravity, McFarland says the latest reentry of its W-Series capsule in May illustrates that the design is ready-made for testing hypersonic technologies.

For each flight, a satellite connected to a capsule is lofted to orbit by a SpaceX Falcon 9. The capsule can spend days or weeks manufacturing the desired material or substance for a commercial customer. For its latest flight, which began in June, the plan is to make proprietary pharmaceutical crystals from a liquid solution. Once manufacturing is complete, the satellite ejects the capsule to return to Earth. During reentry, the capsule reaches speeds up to Mach 25 and is subjected to extreme vibrations and plasma-inducing heat — 17,700 C, hotter than the sun’s surface.

“It seemed like a natural coupling of what DOD wanted to do,” McFarland says.

So far, Varda has flown three capsules, each one carrying pharma materials and technology aboard for testing under hypersonic conditions: a plasma-measuring spectrometer for the U.S. Air Force Research Laboratory, an inertial measurement unit for the Air Force and thermal protection materials for NASA. Some prospective commercial customers, whom McFarland declined to name, have also inquired about testing their technology under the hypersonic reentry conditions.

Varda designed its capsules to reenter the atmosphere at a shallow angle to minimize the shock and vibrations for the pharma cargo, but if hypersonics customers wanted to pay to have some capsule flights all to themselves, McFarland says that trajectory could easily be altered to maximize vibration or other conditions.

“If we’re going to make a business decision like that, it’s going to have to be lucrative,” he adds. “We are focusing on a firm fixed price, so you can get under $10 million for a turnkey launch” that includes the launch, orbit, recovery of the capsule after a parachute landing, delivery of the cargo back to the customer and analysis of the flight.

That’s similar to the price that Rocket Lab is offering for flights aboard the suborbital version of its satellite-launching Electron rocket, says Rogers. It seems like a lot of money, but not in comparison to the $100 million DOD was paying when it was conducting only one test per year.

Each HASTE — short for Hypersonic Accelerator Suborbital Test Electron — can launch and release a 700-kilogram payload from its nosecone fairing. This payload can be provided by a customer, or Rocket Lab can provide one that customers can bolt their test items to. HASTE’s liquid-fueled engines are throttleable and gimbaled, so the trajectory can be shaped, Rogers says — for instance, a parabola for an intercontinental ballistic missile-type trajectory, or a shallower angle better suited for releasing a winged, boost-glide vehicle.

Later this year, Rocket Lab plans to perform a “direct inject,” in which a HASTE will be launched and then commanded to turn horizontally and accelerate before releasing its hypersonic test payload, Rogers says. Three HASTEs have been flown so far, all in the last two years and each with expendable payloads that splashed into the ocean, but Rogers says the design is also capable of releasing reusable hypersonic vehicles that land on runways or parachute to land for recovery.

Rocket Lab builds an Electron rocket every 10 days and would like to launch at least one HASTE per month, he says. “There are a variety of payloads that have been waiting a long time to get a flight test, and now that the flood gates are open, I think you’ll see a higher cadence of tests.”

Krevor, the Stratolaunch CEO, hopes at least a handful of those will be aboard his company’s Talon-A vehicles. The goal is to conduct one hypersonic flight test per month by the end of 2025, and then increase that cadence to a flight every two or three weeks. One of the Talons has completed two flight tests for Virginia defense contractor Leidos, under a MACH-TB contract. Stratolaunch plans to fly a second Talon-A by year-end and eventually have three in rotation, refurbishing them between flights by replacing the black thermal tiles on their leading-edge surfaces, if necessary, and their white insulation blankets.

So far, Krevor says that this reusability has already helped Stratolaunch drive down flight costs. A Talon-A test flight is about “two orders of magnitude” down from the $106 million per flight that the Congressional Research Service once cited, Krevor says, which works out to $3.2 million.

Finding the market

For now, DOD and its contractors still constitute the majority of the demand — about 80% of the potential market versus 20% for commercial and civil uses, Krevor says — but he expects that ratio to shift to 65/35 as companies refine their concepts for hypersonic cargo and passenger planes.

In anticipation of this, Stratolaunch also plans to add a second carrier aircraft to its fleet: a Boeing 747 modified to carry a Talon-A on its belly that could potentially take off from runways near the test ranges of ally countries. The U.S. Missile Defense Agency is funding the modifications and one Talon-A test flight through a $24.7 million contract.

Judging from U.S. budget figures, it appears that many more such contracts are on the way for other test flight providers as well. Funding for more and more test flights will drive down the cost of those flights, just as the government funding for SpaceX development and frequent flights drove down launch costs for the space industry, says Crowe of NSTXL. “It’s going to dramatically reduce the cost.”

“The technology is there; the funding is there,” says Rogers of Rocket Lab. “It’s a perfect match.”

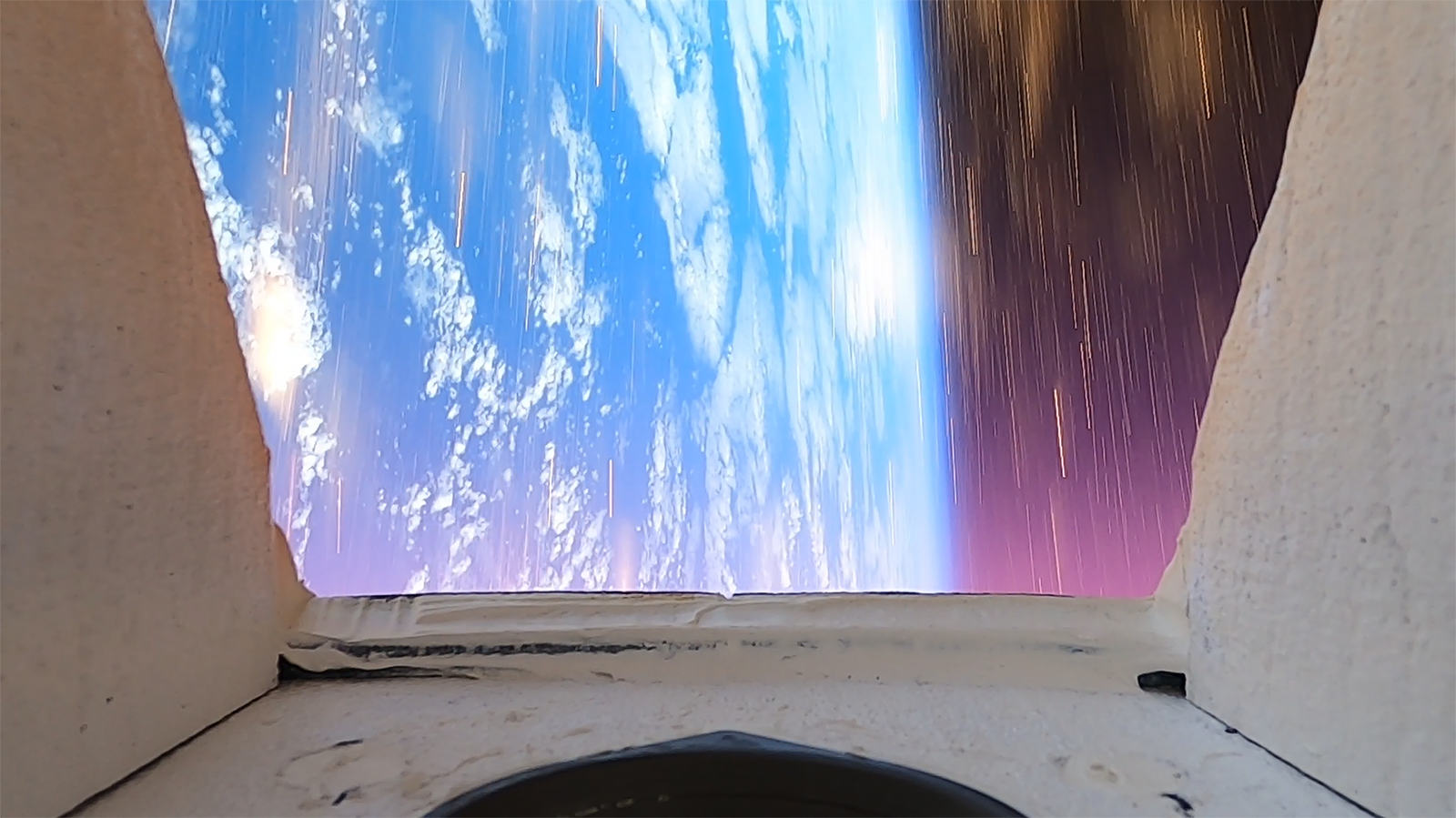

Opening image: Small launch provider Rocket Lab launched its second HASTE vehicle in November 2024. Credit: Rocket Lab

About Keith Button

Keith has written for C4ISR Journal and Hedge Fund Alert, where he broke news of the 2007 Bear Stearns hedge fund blowup that kicked off the global credit crisis. He is based in New York.

Related Posts

Stay Up to Date

Submit your email address to receive the latest industry and Aerospace America news.