Stay Up to Date

Submit your email address to receive the latest industry and Aerospace America news.

Two of the leading satellite companies planning to roll out direct-to-cellphone internet have opposing strategies for addressing an age-old challenge: how to compete with terrestrial communications.

Let’s first look at SpaceX’s plan to establish “cell towers in the sky” that will connect directly with your phone. The data rates won’t match cellular 5G or even the current Starlink constellation, but SpaceX sees a market because Starlink is not practical for all users. A rectangular auxiliary antenna must be set up outside on a stand or be attached to a building or car with suction cups.

Since January, SpaceX has been launching a new class of Starlink satellites tailored for this service starting in 2025. Ultimately, thousands will be launched, each with a 25-square-meter antenna that forms up to 43 spot beams — the term for a tightly focused transmission to a specific area. This compares to some 16 spot beams for the 1-meter antenna on each conventional Starlink. The more spot beams, the more customers can be served. The new satellites are also being sent to VLEO, or very low Earth orbit, specifically 350 kilometers. That’s some 200 km lower than the other Starlinks.

Flying lower means the beams spread less, although now a bigger antenna is needed to connect directly to phones. Some 200 of these Starlinks have been launched for testing, but SpaceX’s application with the Federal Communications Commission to launch the full VLEO constellation remains under consideration.

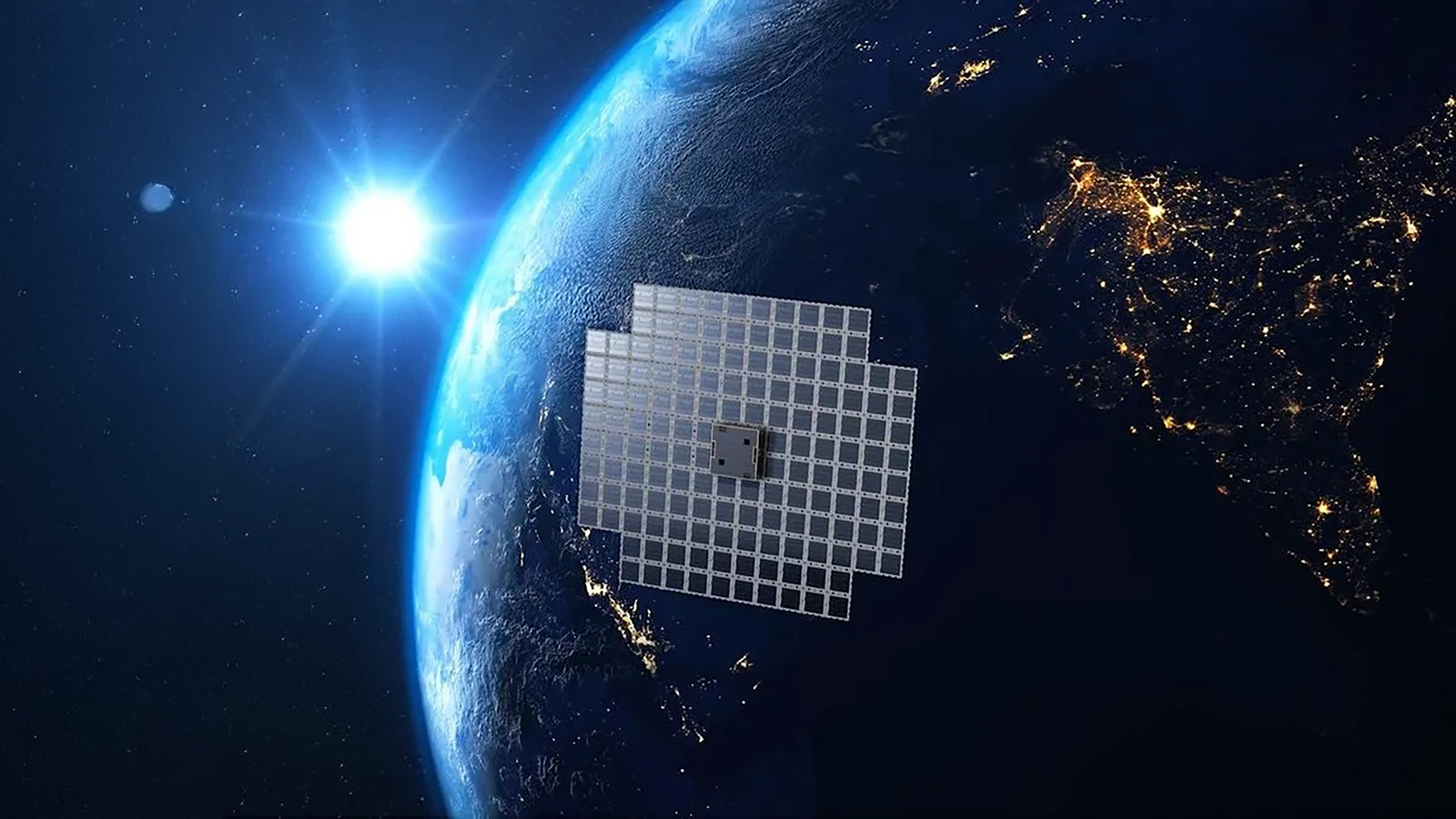

Meanwhile, a 2017 startup, AST SpaceMobile of Texas, is employing a different tactic: Send far fewer satellites — about 200 — to LEO at 500 and 700 kms in altitude. AST plans to make up for the greater distance and fewer satellites with large antennas that generate more powerful beams and receive the weak signals from smartphones. Orbiting in LEO instead of VLEO means less atmospheric drag, so the satellites remain in orbit longer. These will have much larger antennas than Starlinks — 63 square meters initially but increasing to 223 square meters on later satellites.

In September, AST launched five satellites it calls BlueBirds to test the idea further than it did with its BlueWalker 3 prototype in 2022. Each satellite’s antenna will produce up to thousands of 48-km-wide spot beams through the company’s proprietary digital beam-forming technology, says Huiwen Yao, AST’s chief technology officer. Each satellite will service customers in a 5,600-square-km area. AST’s FCC license to launch the full constellation is pending.

One thing the competitors have in common are agreements with cellular providers to provide service on existing 5G and other terrestrial networks. SpaceX has partnered with T-Mobile, and AST has gone with AT&T and Vodafone.

SpaceX in March reported achieving a speed of 17 megabits per second in tests with the satellites launched so far. With its BlueWalker 3 prototype, AST said it’s achieved 21 megabits per second — enough for basic internet connectivity and web browsing, although Yao says speeds of at least 120 megabits per second are possible.

The 120 rate still does not quite match terrestrial services. At least for now, such services are “not a substitute for terrestrial networks,” says Tim Farrar, a satellite communications expert in California.

About Jonathan O'Callaghan

Jonathan is a London-based space and science journalist covering commercial spaceflight, space exploration and astrophysics. A regular contributor to Scientific American and New Scientist, his work has also appeared in Forbes, The New York Times and Wired.

Related Posts

Stay Up to Date

Submit your email address to receive the latest industry and Aerospace America news.