Stay Up to Date

Submit your email address to receive the latest industry and Aerospace America news.

Russia and China are raising their defenses against stealth technology with improved radars, longer-range missiles, cloud computing and even stealth planes of their own. These trends make continuous improvement to stealth, such as through the forthcoming B-21 long-range strike bombers, a necessity if the U.S. is going to maintain its offensive edge, according to a report published by The Mitchell Institute for Aerospace Studies, a think tank in Virginia.

The F-35 fighters built by Lockheed Martin are an example of staying ahead, particularly with their improved radar-absorbing skin coating, noted one of the report’s authors, retired Air Force Maj. Gen. Mark Barrett. “There is vast improvement from the F-22 to the F-35 on the material that they use, the durability of it,” Barrett said during a Wednesday event held to present the report.

Barrett, who from 2007 to 2009 commanded the first operational wing of F-22 fighters, said it was difficult to maintain the radar-absorbent coating on F-22s because of the heat they endure when flying at top speeds. Barrett, a visiting fellow at the Mitchell Institute, said he expects the coating on the B-21 to be as durable or more durable than the F-35. The aircraft’s design is classified.

The mission requirements and cost concerns of fighter jets are a challenge for engineers designing a stealth plane. The F-35 design sacrifices some radar stealth with its vertical tail fins. Its exposed engine nozzle means its heat signature is not as low as it could be. These design elements are necessary because they aid its speed and maneuverability.

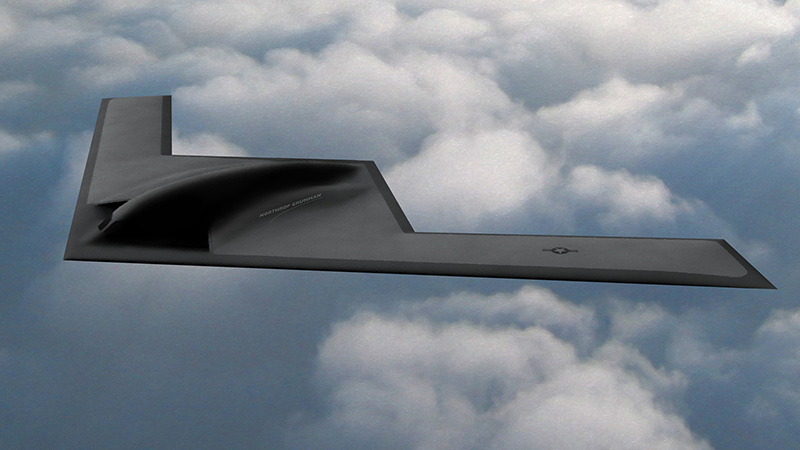

Bombers don’t need the maneuverability of fighter jets, so designers of the decades- old B-2 bombers achieved low radar visibility by not including a vertical tail fin. The Air Force has released an artist’s rendering of the B-21 bomber (seen at the top of this article) that indicates a flat aircraft design with no tail fin, a strategy that should make it harder to spot on radar, although the final design remains a secret. The artist concept does not depict the plane’s engine or exhaust vents, which are the key to a low infrared signature. On the B-2, engineers decided to direct air into engines nestled in the top side of the body of the aircraft and dissipate the exhaust heat across the top to reduce chances of detection by infrared sensors.

“Roughly 85 percent of the stealthiness of a platform is the shape, and the other 15 percent is the coating,” says one of the report’s authors, retired Air Force Col. Mason Carpenter.

In a sign of changing times, the computing power of new stealth aircraft is one of the most classified details of the planes, because decoying or disrupting an enemy’s sensors could be among the best defenses, says Carpenter, a senior fellow at the Mitchell Institute. By 2022, a quarter of U.S. combat air forces will be stealthy, and that ratio should increase as F-35s and B-21s enter service while non-stealthy aircraft retire, according to the report, named “Survivability in the Digital Age: The Imperative of Stealth.” Nations including China and Russia are working on new ways to search for stealth airplanes, including by tracking their noise footprints at long range or their heat signatures. Those technologies are less proven and less widely used than conventional radio frequency radar, Barrett said.

“The threat for the foreseeable future for airborne assets is going to be radar,” he said.

The F-117 fighters that debuted in the 1980s showed the world the strike capability of radar stealth by making the first aircraft strikes on Baghdad during the 1991 Persian Gulf War. Radar absorbent coating has come a long way since Desert Storm, says Carpenter, who flew F-117 missions during the 1999 NATO bombing in Kosovo. The Kosovo war with Yugoslavia brought the only shoot down of an F-117.

When he was a younger officer, retired Air Force Lt. Gen. David Deptula helped plan the air campaign in the 1991 Persian Gulf War. Deptula, who is now dean of the Mitchell Institute, says stealth aircraft flew less than 2 percent of the total combat sorties, but attacked over 40 percent of the fixed strategic targets during that war, which demonstrates their cost-effectiveness.

“A single stealth aircraft can perform the missions that many non-stealth aircraft are required to equal,” Deptula says.

Other nations have learned the value of stealth in recent decades and are developing their own stealth aircraft, in part by studying and reverse engineering U.S. technology. These include China’s Chengdu J-20 fighters and Russia’s Sukhoi T-50 PAK FA fighters, which have been renamed the Su-57 as the Russian fighter nears mass production, according to media reports.

“While Russia, China and others are trying to mimic the results the U.S. has already achieved, it will be many years before they reach U.S. levels of capability due to both technological and financial challenges,” Deptula says.

Purchasing stealth aircraft and anti-air defenses to reduce the effectiveness of stealth, however, still leaves the challenge of training personnel to field those technologies and operate them with other equipment, which gives the U.S. the edge as the most battle-tested stealth power, Barrett said.

“There is vast improvement from the F-22 to the F-35 on the material that they use, the durability of it.”

retired Air Force Maj. Gen. Mark Barrett, co-author of the report "Survivability in the Digital Age: The Imperative of Stealth"

About Tom Risen

As our staff reporter from 2017-2018, Tom covered breaking news and wrote features. He has reported for U.S. News & World Report, Slate and Atlantic Media.

Related Posts

Stay Up to Date

Submit your email address to receive the latest industry and Aerospace America news.