Stay Up to Date

Submit your email address to receive the latest industry and Aerospace America news.

The Nuclear and Future Flight Propulsion Technical Committee works to advance the implementation and design of nonchemical, high-energy propulsion systems other than electric thruster systems.

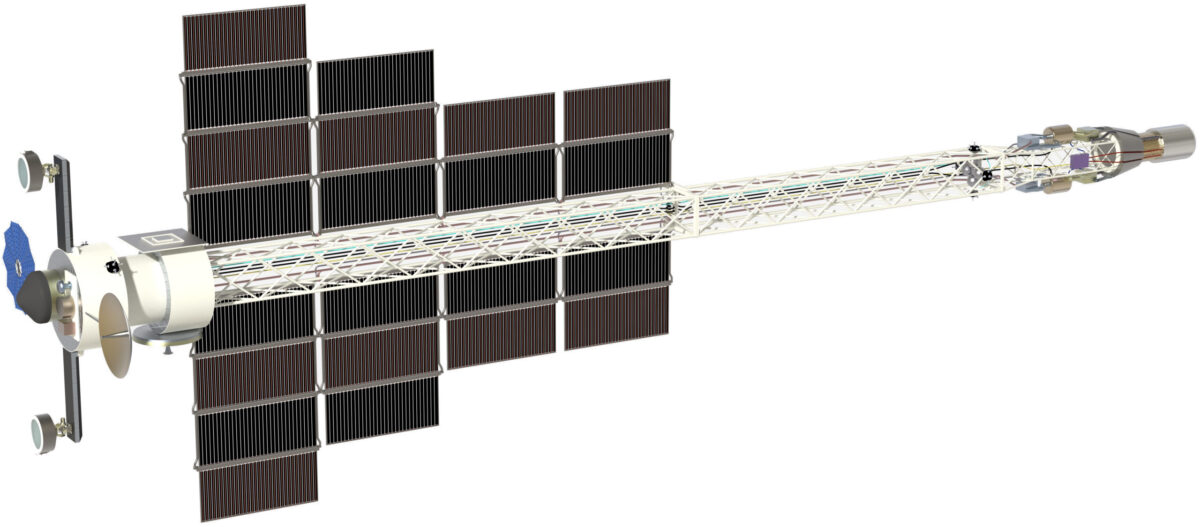

At AIAA’s SciTech Forum in January, Aerojet Rocketdyne presented a concept for a Neptune Orbiter space vehicle that would use nuclear electric propulsion. Neptune is an ice giant planet with a fascinating and dynamic atmosphere and several intriguing moons, including Triton. The maximum electric power level for the orbiter was 50 kilowatts electric (kWe), and the launch mass was limited to 60 metric tons by the chosen launch vehicle, a SpaceX Falcon Heavy. The paper’s authors analyzed several types of advanced electric propulsion ion engines. They found the trip to Neptune would take 12 to 14 years.

The orbiter would use a nuclear reactor and power conversion system, or PCS, to produce enough electrical power to run an advanced ion propulsion system, mission module instruments and an orbiter bus. Depending on the required power level of the orbiter, the reactor and PCS designs have the potential to be taken directly from NASA’s Fission Surface Power program, which specifies a 30-50 kWe power level range.

Using two large radiator wings, excess thermal power would be radiated to space as waste heat. The radiator panels would utilize titanium-water heat pipes and composite fins, similar to those previously developed and tested by NASA’s Glenn Research Center.

In mid-2025, Princeton Satellite Systems completed a preliminary design of Starfire-1, a subscale prototype, with the goal of reaching fusion-relevant temperatures in preparation for the full-scale prototype, Starfire-2. Starfire is a van-sized fusion reactor designed to provide megawatt-level power, as well as a direct method of fusion propulsion for spacecraft. Starfire uses a patented radio frequency heating approach with a linear array of magnets roughly the size of those in MRI machines to enable a smaller and simpler-to-build fusion system.

Starfire’s magnetic fields form a field-reversed configuration, resulting in a high plasma-to-magnetic pressure ratio that decreases size significantly. Starfire runs on deuterium-helium-3 fuel to nearly eliminate damaging neutrons, increase operational life and decrease shielding mass and radioactivity. Starfire could enable trips to Mars in two months instead of the nine typical with chemical propulsion. It could also serve as a reactor at its destination, providing megawatts of power on the moon or Mars.

At AIAA’s ASCEND conference in July, NASA Glenn researchers presented their assessment of a number of mining and transportation machines needed at the ice-giant moons of Uranus and Neptune. The overall mining architecture masses were estimated using 10-, 20-, and 30-year delivery schedules. The delivery schedules included the major architecture components: the nuclear gas-core atmospheric mining aerospacecraft, the nuclear electric orbital transfer vehicles, the moon landers and the nuclear in-space factories.

The mining issues will be critical to making operations successful. Capturing the regolith and water ice mix and separating the water ice from the regolith are major challenges. Purification of the water ice and the resulting oxygen and hydrogen propellants will be another serious consideration.

Numerous machines will likely be needed for the mining of water ice: machines for mining, hauling and hoppers to transfer the water ice to a factory for purification and separation into oxygen and hydrogen. With very small mining machines, the number of machines needed is very high. Mining 100 metric tons of water with mining machines that carry 1 metric ton, for example, would require more than 100 machines. For a 100-metric ton water mining operation, if the water fraction is 75%, using a 10-metric ton payload machine, approximately 14 machines would be needed. Based on past remote measurements and data analyses, the water ice fraction on the moons of Uranus should be very high, making mining more efficient.

Opener image: An illustration of Aerojet Rocketdyne’s concept for a nuclear-electric Neptune Orbiter. Credit: Aerojet Rocketdyne/Timothy Kokan

Stay Up to Date

Submit your email address to receive the latest industry and Aerospace America news.