Stay Up to Date

Submit your email address to receive the latest industry and Aerospace America news.

Parachute troubles not unique to Commercial Crew

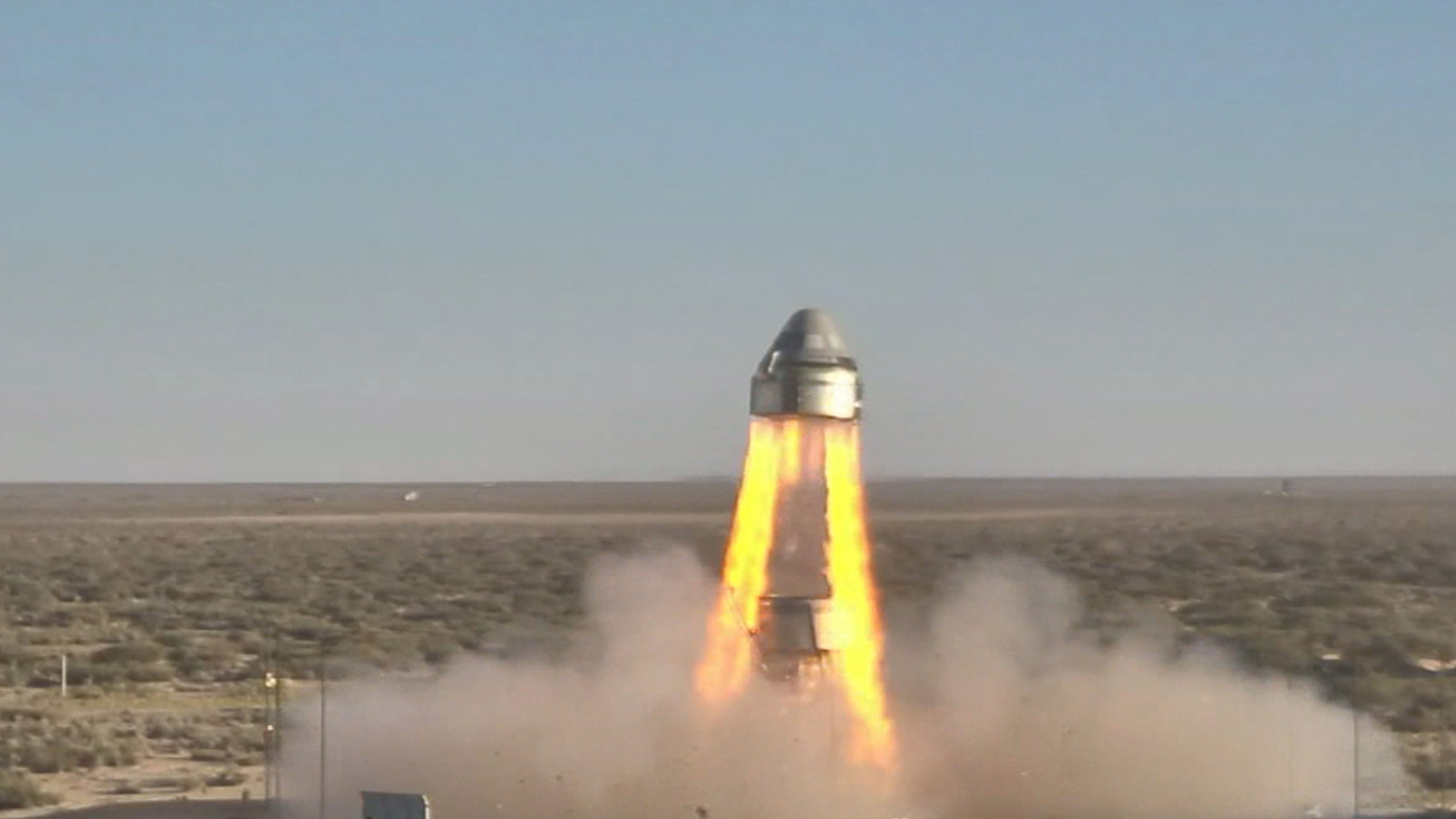

Moments after the Boeing CST-100 Starliner landed in the New Mexico desert, the livestream narrators from Boeing and NASA declared the capsule’s first flight an “absolutely beautiful sight.” Undercutting that excitement was the fact that one of the parachutes failed to deploy.

The trouble occurred at the tail end of the pad abort test, in which Boeing flight controllers at White Sands Missile Range fired the collection of engines and thrusters that would whisk Starliner and its crew away from a fizzling or exploding launch vehicle. At an altitude of about 1.5 kilometers, Starliner’s sequence of parachute deployments began, but one of its three main parachutes did not deploy.

“Although designed with three parachutes, two opening successfully is acceptable for the test parameters and crew safety,” NASA said in a statement released about an hour after the test.

When I contacted Boeing for clarification, spokesman Josh Barrett told me Starliner had “a deployment anomaly, not a parachute failure.”

Among those watching the NASA livestream was Jonathan McDowell, a Harvard professor who writes the Jonathan’s Space Report newsletter cataloging launches. He was surprised by NASA’s upbeat reaction.

“Sure, two out of three is OK on an actual flight, but on a test, you want things to go right,” he said. “You want to make sure there’s not some generic problem in the system.”

“It’s concerning,” he added, “especially in the context of other recent parachute problems.”

A July 2018 report from NASA’s Government Accountability Office found that parachute certification for both Starliner and the SpaceX Crew Dragon has been one of the biggest reasons for delays in the Commercial Crew program; nearly two years past the 2017 deadline, neither contractor has flown crew. NASA is counting on these contractors to restore the country’s ability to launch American astronauts from American soil and end U.S. reliance on Russian Soyuz spacecraft that have been NASA’s sole method of transportation to the International Space Station since 2011.

These difficulties are not without precedent. Take the Apollo 15 mission, in which one of the main chutes deflated during landing. The spacecraft splashed down in the Pacific Ocean with its two remaining parachutes without injury to the crew. A post-mission analysis later faulted missing shroud lines, or the thin cords that attached the parachute’s canopy to the riser that pulled it from the spacecraft during deployment.

More recently, the European Space Agency said in June that the parachutes for its ExoMars 2020 rover “suffered unexpected damage” during a drop test earlier that month.

Part of the difficulty, McDowell said, is that because parachutes are “floppy systems, fabric and ropes all packed in, it’s maybe not as amenable to rigid analysis as the plumbing of a rocket engine.”

But he thinks those difficulties are more understandable for a parachute that must survive the extreme Martian environment versus the ones for Commercial Crew that have been proven throughout the last 60 years of human spaceflight.

“We’ve been doing parachutes on returning capsules for a long time, so you’d think by now we’d know how to do this,” he said.

It’s too early to know the cause of Starliner’s parachute troubles during Monday’s test, Barrett the Boeing spokesman told me. Boeing will review data captured by gravity sensors on a test dummy inside the spacecraft to see how many G-forces astronauts would have encountered. In the meantime, NASA doesn’t expect a delay for Starliner’s first uncrewed flight, currently scheduled for Dec. 17. For that test, Starliner will launch atop a United Launch Alliance Atlas V rocket and dock with the space station.

About cat hofacker

Cat helps guide our coverage and keeps production of the print magazine on schedule. She became associate editor in 2021 after two years as our staff reporter. Cat joined us in 2019 after covering the 2018 congressional midterm elections as an intern for USA Today.

Related Posts

Stay Up to Date

Submit your email address to receive the latest industry and Aerospace America news.