Stay Up to Date

Submit your email address to receive the latest industry and Aerospace America news.

Cameras that once watched space shuttles ascend will image sun, Mercury

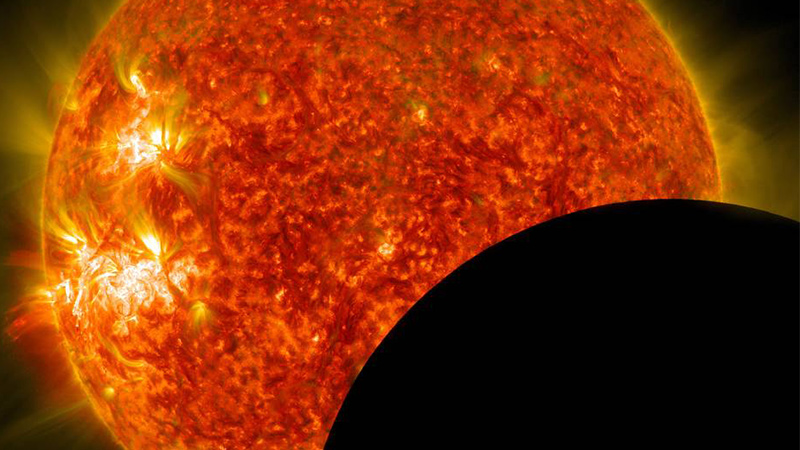

When the moon completely eclipses the sun on Aug. 21, scientists will take the opportunity to study the sun’s corona with cameras mounted on NASA research planes in a mission that participants say could spur more airborne astronomy.

The eclipse will be the first in 99 years to cast a shadow that will cross the entire continental U.S., giving American scientists easy access to view the sun’s atmosphere, or corona, which will be visible from behind the moon.

NASA has readied two of its three WB-57 research planes for the mission which was proposed by scientists from the Southwest Research Institute’s office in Boulder, Colorado. These converted Martin B-57 bombers were first designed in the 1950s. Typically the high-definition, infrared video cameras on their noses monitor rocket launches for NASA and conduct “security missions” for the Department of Defense. This will be the first time they photograph the sun or a celestial body, says Charles Mallini, program manager for the WB-57s. The planes will follow the moon’s shadow above the clouds at 50,000 feet, beginning near Carbondale, Illinois, with one flying nearly 110 kilometers behind the other to collect about three and a half minutes of footage each for a total of eight minutes, Mallini says. This mission “opens up a whole new window of opportunity” to inspire other scientific groups to partner with NASA and its research planes, he says.

“We hope it gets people thinking about similar types of airborne astronomy,” Mallini says.

These unique images could help solve the mystery of why the sun’s atmosphere is hotter than its surface, says Amir Caspi, principal investigator for the eclipse observing program and a senior research scientist at SwRI’s Boulder office.

“We know that energy is getting up there, we just don’t quite know how, and one of the ways we think it might be happening is transfer through its magnetic field,” Caspi says.

This brief moment in the moon’s orbit also provides a chance to take unusually clear high-definition and infrared video to study the surface temperatures of Mercury, which is typically obscured by sun’s brightness. Scientists also will search for vulcanoids, the term for small asteroids that some scientists theorize are orbiting the sun inside of Mercury’s orbit.

Southern Research, a nonprofit technology organization based in Birmingham, Alabama, began designing a camera-aiming turret for the WB-57 in 2003 to take high-definition video of space shuttle launches. In February of that year, the Columbia orbiter disintegrated during its return to Earth after insulating foam struck its left wing during launch.

Today, the unit consists of a turret, called the Airborne Imaging and Reconnaissance System, which moves the camera, called DyNAMITE, short for Day Night Airborne Motion Imagery for Tactical Environments. On the eclipse mission, an operator will fly in the backseat of each plane to maneuver and focus the cameras and lenses while wearing a protective visor, says Johanna Lewis, director of program management at Southern Research’s engineering division.

One significant optical adaption was required. The solar atmosphere has some metal in it, including super hot iron-14 ions that emit green light, so a green filter will make it easier to spot those emissions, Caspi says.

The planes were flown on July 6 for a test of the green filter mounted on the lens and new recording software to download better quality video without compressing it, Caspi says. Another test flight on Aug. 9 near Houston will test upgrades to the satellite uplink that will ensure a better connection for scientists watching streaming video coming from the plane via satellite during the eclipse, he says. Airborne astronomy missions are already flown by NASA’s Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy, a modified Boeing 747SP that carries a reflecting telescope, but flying it during the day is risky because its mirror could collect too much light, Caspi says.

Editor’s Note: This story has been updated to correct the description of vulcanoids and provide additional details.

About Tom Risen

As our staff reporter from 2017-2018, Tom covered breaking news and wrote features. He has reported for U.S. News & World Report, Slate and Atlantic Media.

Stay Up to Date

Submit your email address to receive the latest industry and Aerospace America news.