Stay Up to Date

Submit your email address to receive the latest industry and Aerospace America news.

Silicon Valley tests aim to assess passenger motion sickness

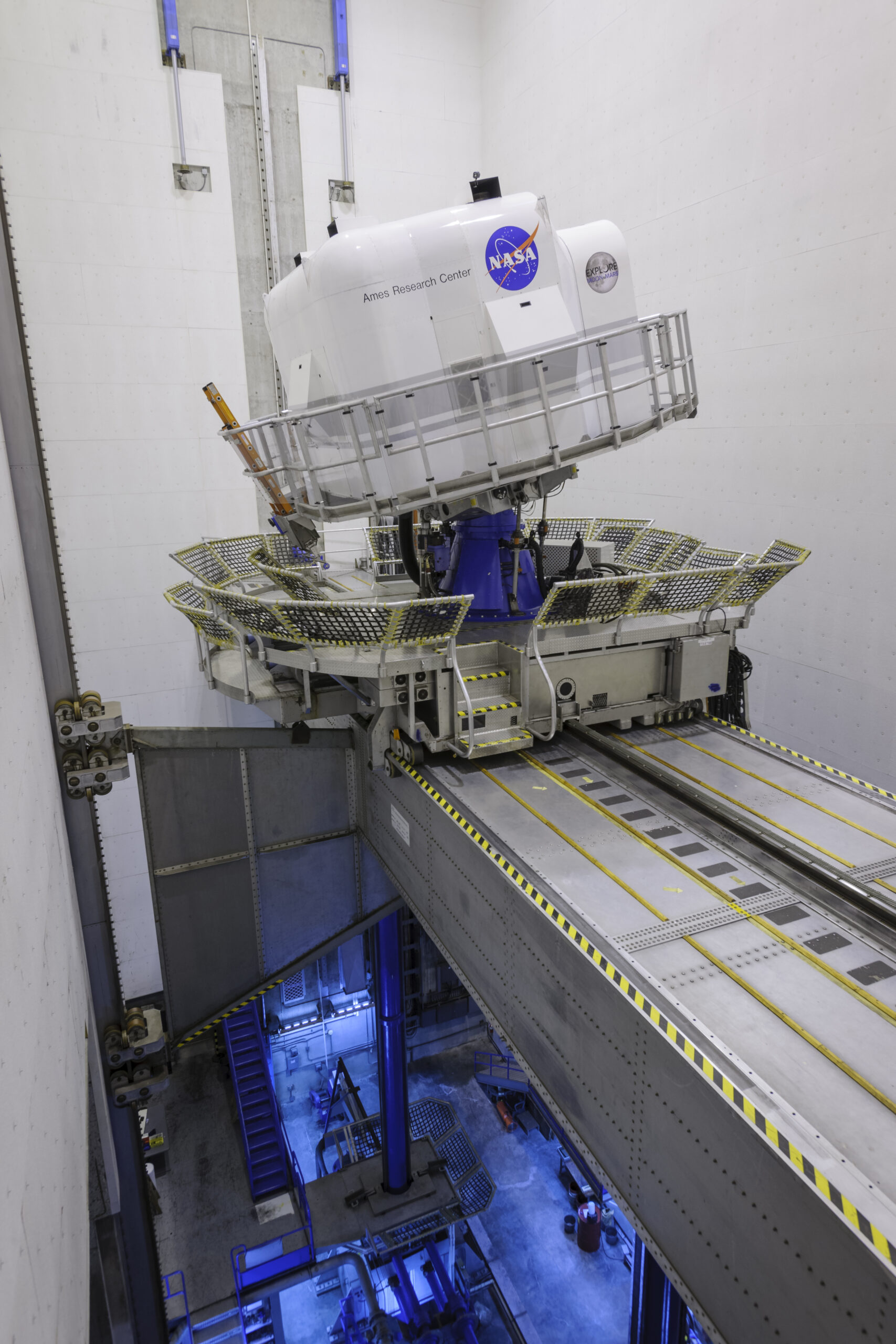

The Vertical Motion Simulator at NASA’s Ames Research Center has a storied past, helping train astronauts and F-35 pilots alike. Now, the world’s largest full-motion simulator could pave the way for urban air mobility, a future in which passenger air taxis could share the skies with package delivery drones and other cargo vehicles.

But if this vision of millions of commuters in the U.S. is to become reality, designers will need to be confident that passengers won’t become motion sick in these small rotorcraft.

“For the urban air mobility market to develop and mature and hopefully survive, the make-or-break element is how a typical passenger would perceive their ride quality,” says research engineer Robert Fong of Ames, located in California’s Silicon Valley.

To simulate an air taxi flight, Fong’s team of engineers designed and built a four-person cockpit, called the Ride Qualities Cab, whose interior resembles that of a generic air taxi. Simulator designers call such modules “cabs,” and this new one is one of five that can be attached to the Vertical Motion Simulator, or VMS, to mimic various aircraft and spacecraft by moving them vertically and side to side on a motion base.

Few commuters or other urban travelers have experienced “the types of motions that you would experience in a hovering vertical aircraft,” says NASA’s Carlos Malpica, technical lead for the Flight Dynamics and Controls program at Ames. “That’s what’s new, that’s what’s different, and that’s what we’re trying to understand.”

Plans call for Ames Director Eugene Tu to take a whirl in the simulator in 2020, and for average prospective passengers to someday take turns in the cab. NASA would document “envelopes of motion that the human can tolerate,” Malpica says. That data could then be used by companies to refine their air taxi designs.

“The target market is a regular passenger that expects to step into a taxi and be flown from point A to point B,” says Fong, project manager for the Ride Qualities Cab initiative, not someone like a helicopter pilot who’s accustomed to the “types of accelerations” these future air taxis will likely experience.

The scenario currently loaded in the cab begins at a vertiport along San Francisco Bay, which passengers see on the wrap-around screens in the cockpit as simulated by the VMS Lab computer. The VMS motion base then begins to move, and those in the cab “would feel the acceleration as if you were taking off,” Fong says, which researchers create by commanding VMS to move up to 18 meters vertically, the equivalent of a 10-story building.

VMS can also move 12 meters from side to side to mimic the turbulence passengers might feel during flight. That’s important to model, Fong says, because future air taxis will have to navigate around buildings and through “swirling winds” that may make for a less than smooth ride. The Ride Qualities Cab simulation will take passengers through a wind field, coming in for a landing at a vertiport in the middle of San Francisco.

Fong and his team plan to upgrade the simulation as the initiative unfolds. Eventually, the Ride Qualities Cab will also “simulate the noise that a passenger would experience flying in one of these vehicles,” he says, another element of ride quality. Future riders could also wear biometric sensors to measure heart rate, nausea and other physical changes.

And because the initiative has no projected end date, the Ride Qualities Cab itself could change over the course of the tests, Malpica says, adapting in response to what the researchers learn.

About cat hofacker

Cat helps guide our coverage and keeps production of the print magazine on schedule. She became associate editor in 2021 after two years as our staff reporter. Cat joined us in 2019 after covering the 2018 congressional midterm elections as an intern for USA Today.

Related Posts

Stay Up to Date

Submit your email address to receive the latest industry and Aerospace America news.