Stay Up to Date

Submit your email address to receive the latest industry and Aerospace America news.

NASA remains determined to catalyze a competitive market with seed money

LAS VEGAS — A question looms over the companies that are planning to build their own free-flying space stations: Whether enough research and space tourism dollars will flow through the market to keep more than one of them in business.

The answer to that question could come relatively soon, at least on the time scale of the space marketplace. The U.S. Congress has so far committed to funding NASA’s portion of the International Space Station only through 2024, although NASA has told Congress that, physically speaking, the station could be operated safely by the partners through 2030. In its post-ISS era, NASA wants to rent research space on multiple privately owned stations, the idea being to nurture a competitive marketplace with prices to match. To catalyze that vision, the agency plans to soon announce the winners of its Commercial LEO Destinations competition in which $400 million in seed money will be distributed among two to four competitors who can apply the funds to designing and constructing their space hardware.

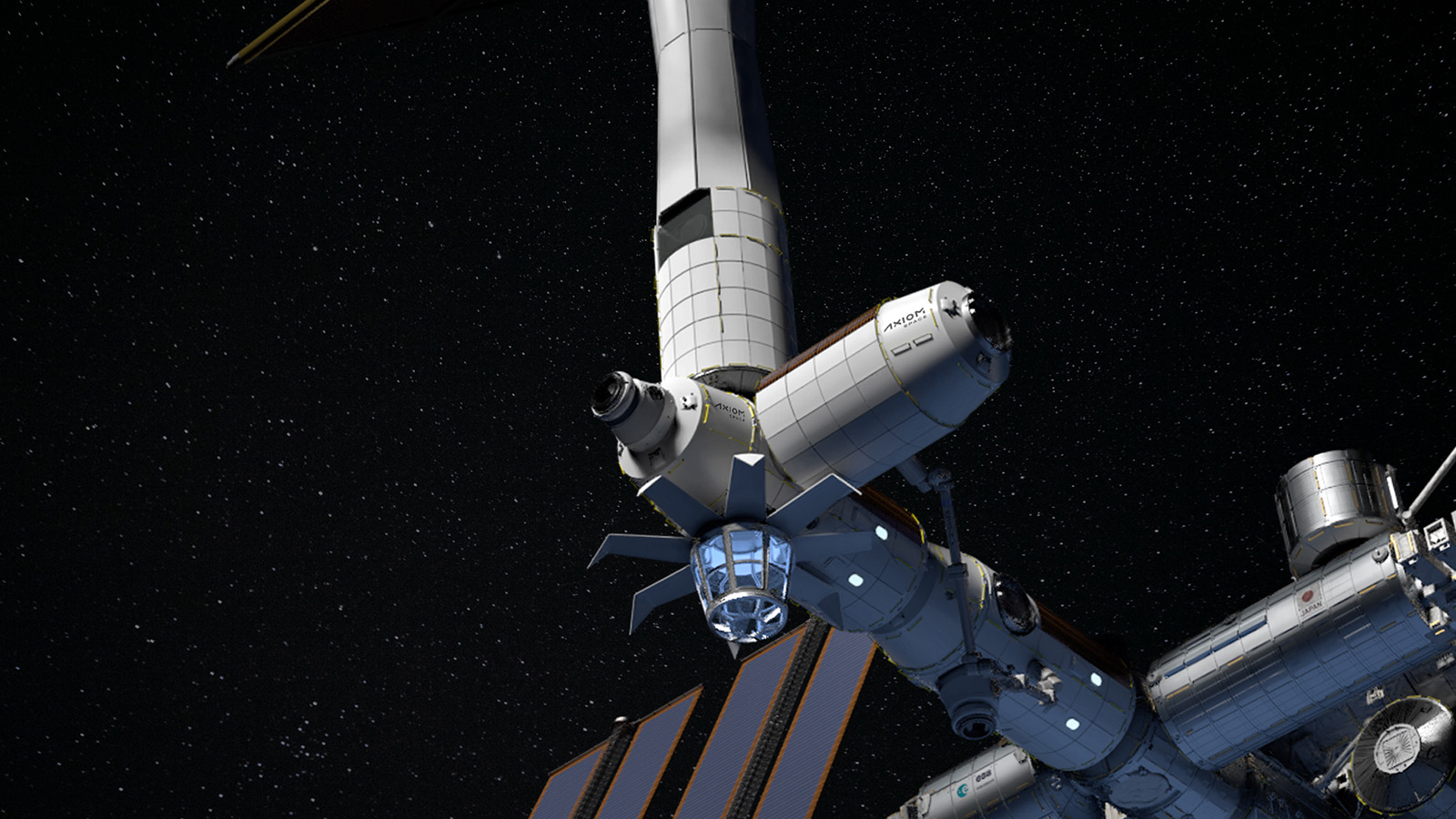

The competitor in arguably the strongest position is Axiom Space. The company plans to send its first three space tourism customers to ISS aboard a SpaceX Crew Dragon in late February. Axiom also plans to attach its initial modules to ISS, starting with a habitation module in 2024, and conduct research and host tourists aboard for at least four years of confidence building.

Axiom thinks it’s in a solid position overall, but Mary Lynne Dittmar, Axiom Space executive vice president for government affairs, did share one worry with me during an interview ahead of AIAA’s ASCEND conference here. Multiple privately owned stations could “end up diluting the market to such an extent” that no one is profitable and there’s no U.S. presence in low-Earth orbit, she said.

Another company vying for the NASA dollars has a more optimistic take.

“I think the market can sustain many more than one space platform because the issue that we’re seeing today is one of access on the ISS,” said Adrian Manguica, vice president of infrastructure at Voyager Space Holdings, the Denver conglomerate that is vying for some of the $400 million, during an interview here.

Managers of the ISS National Lab, which selects experiments to be conducted by American astronauts on the station, routinely turn away dozens of materials scientists, pharmaceutical companies and others each time it issues a call for proposals to select the next experiments.

Voyager last month announced that Lockheed Martin has joined the endeavor and will build a four-person station to be called Starlab. This facility would be completed by 2027 and operated by Nanoracks, the Houston company that’s majority owned by Voyager and that today leases experiment racks aboard the U.S. portion of ISS.

While Voyager’s investors would provide most of the funds to build Starlab, Voyager is counting on current Nanoracks customers to be among the first users of Starlab so the station can immediately be profitable.

“Customers don’t show up on day one, customers show up at T-minus four years. That’s really what we’re basing a lot of the strategy on,” Manguica said.

And although Manguica wants Starlab to win one of NASA’s Commercial LEO Destination awards, those funds are less about paying for the station and more about the legitimacy that NASA’s “stamp of approval” conveys, he said.

“The consistency and the expectations that NASA brings to the table are really good for our investors,” but ultimately the agency’s seed money would make up “the vast minority” of funding needed for Starlab.

Blue Origin has a different strategy for supplementing the NASA seed money it hopes to win for its Orbital Reef station. It has signed on multiple partners to provide components and services. One of them is Sierra Space, the subsidiary of Sierra Nevada Corp. formed in April. Sierra would provide crew and cargo transportation to Orbital Reef via a future fleet of Dream Chaser spaceplanes. The company’s cylindrical Large Inflatable Fabric Environment, LIFE, habitats would also comprise several of the station modules.

The Dream Chasers and habitat technology have been in development for years and should gain flight experience “well before” Orbital Reef opens for business in 2027, said Janet Kavandi, president of Sierra Space. The first vehicle of the Dream Chaser cargo design, Tenacity, is scheduled for launch atop a United Launch Alliance Vulcan Centaur between November 2022 and February 2023 for a cargo resupply flight to ISS.

As to the demand for future LEO free flyers, Kavandi said the number of governments outside the U.S. interested in on-orbit research provides enough demand that Blue Origin and Sierra Space could possibly require more than one Orbital Reef.

“If we don’t provide that option, they will essentially be cut off to access or they’ll have to go to the Chinese and use the Chinese station,” she said, referring to the Tiangong station, the first module of which China launched in April. “And we would like to really ensure that those countries feel that they can come to the U.S. and still have access to space.”

About cat hofacker

Cat helps guide our coverage and keeps production of the print magazine on schedule. She became associate editor in 2021 after two years as our staff reporter. Cat joined us in 2019 after covering the 2018 congressional midterm elections as an intern for USA Today.

Related Posts

Stay Up to Date

Submit your email address to receive the latest industry and Aerospace America news.