Venturing through the pandemic

By Amanda Miller|April 2021

Here at Aerospace America, we’re not entrepreneurs, but we talk to a lot of them. We can imagine the daunting prospect of vying for venture capital during what we all hope is now a waning global pandemic. Our contributor Amanda Miller went scouting for facts and insights that aspiring entrepreneurs ought to know. Here is what she discovered.

As the covid-19 pandemic hit the United States, experts throughout the venture capital world predicted that investments in startups would drop off, that the VCs — venture capital firms — would opt to reserve cash rather than invest it in case they had to shore up the finances of startups they already had a stake in.

That proved true.

As the pandemic took hold in March 2020, venture investing dropped off steeply, according to a midyear special report by Silicon Valley Bank, known for its tallies of venture investments. The bank called the period a “strange economic moment” of tumultuous fluctuations in venture investment from one month to the next. In its January 2021 report, the bank noted that investors had continued to raise funds but were cumulatively holding back a record $152 billion in reserves. The implication was that an upturn in investing could be at hand as the pandemic eases.

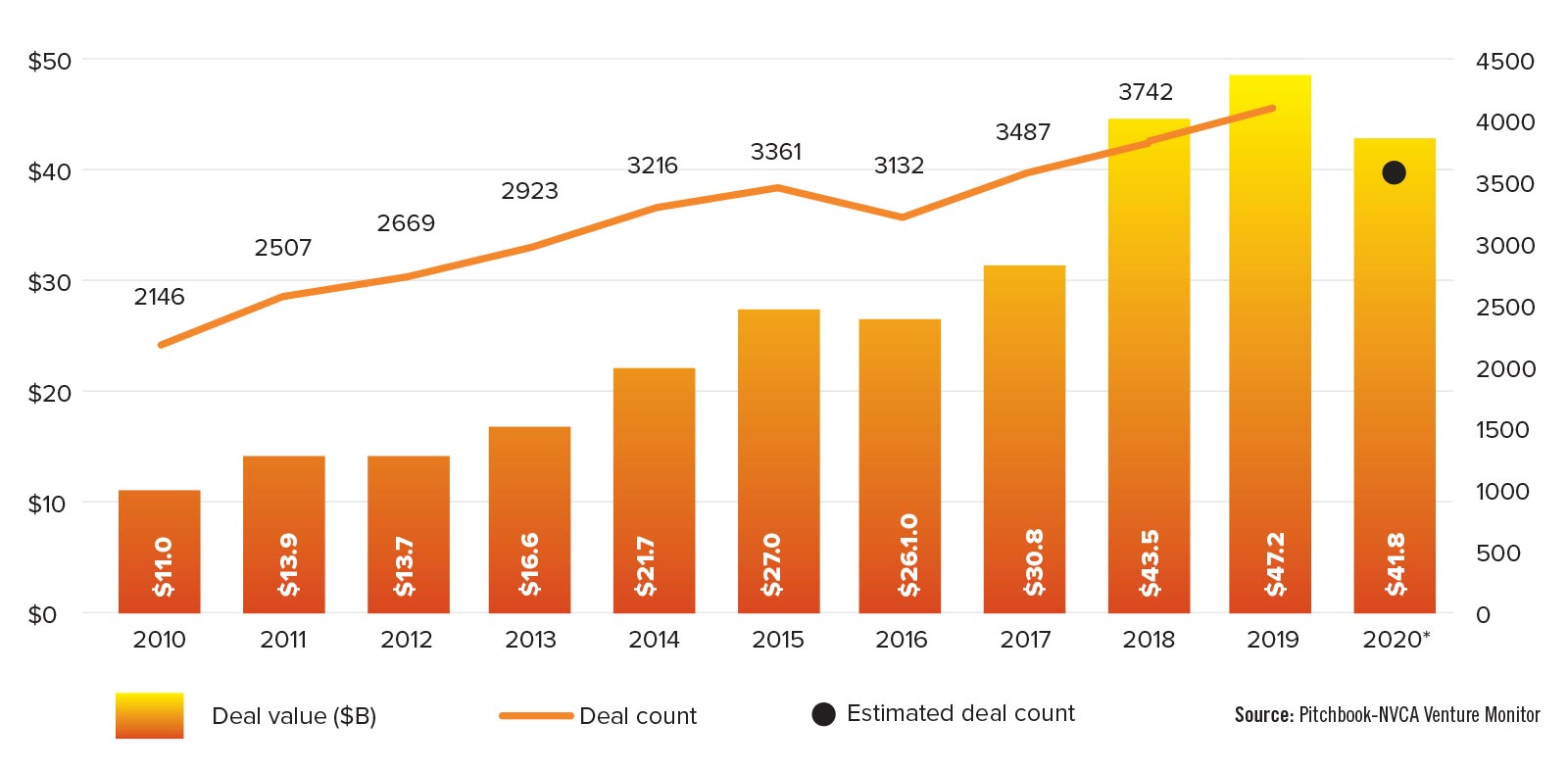

Even with buildup of reserves, investments picked up in terms of numbers of deals and dollar amounts, with 2020 likely topping 2019 in terms of total money, according to Venture Monitor, a quarterly report from the National Venture Capital Association and PitchBook Data, a firm that gathers business information about investors, startups and their deals. However, the growth was still modest compared to what the sector is accustomed to.

One executive said he expects the aerospace sector to suffer less from these fluctuations than other sectors. “The longer time horizon and bigger investment totals” in aerospace tend to buffer new companies from short-term ups and downs, says Chris Moran, general manager of Lockheed Martin Ventures in Palo Alto, California.

“Broad economic problems always cause the startup ecosystem” — both startups and investors — “to pause, belt tighten and then return with a new focus on what will be important post the slowdown,” he predicted.

Moran was one of those who planned to reserve cash in case any startups in his company’s investment portfolio needed it.

Decisions to reserve cash are felt less severely by startups that are already safely in investment portfolios. In 2020, these late-stage startups claimed a larger share of investments, including a record number of “mega-deals,” while the pandemic proved to be “a more challenging fundraising environment for newer entrepreneurs,” including “female founders” who “have traditionally been underrepresented in VC funding,” Venture Monitor said in its January 2021 report.

Of course, investment dollars aside, those still early in the product development phase did not yet have customers to lose due to the pandemic: “They weren’t dependent on that revenue,” Moran says.

Choosing to become VCs

The trend of large aerospace corporations investing in startups began over a decade ago and took off during the past few years, when some of the major contractors realized how furiously startups were innovating.

“There was a sense that the world is rushing ahead,” recalls Logan Jones, who until last June was the Boeing vice president in charge of the company’s HorizonX unit and its venture capital arm. He left to lead a new subsidiary of SparkCognition, an artificial intelligence company in the HorizonX portfolio.

The big three of Airbus, Boeing and Lockheed Martin each now operates a venture capital arm. These units scout for promising startups to add to their investment portfolios, and later these venture arms might help cultivate business leads or loop in technical experts.

Of the three, Lockheed Martin Ventures lays claim to the earliest investments, dating back to 2007, though 36 of the 56 companies Lockheed Martin Ventures has invested in have joined the portfolio just since 2016.

Airbus Ventures started investing in 2016 and lists 39 companies in its portfolio, including the space debris-mapping company LeoLabs, which operates radars in Alaska, New Zealand and Texas to track objects in low-Earth orbit.

Boeing established HorizonX Ventures the following year and has invested in 34 startups, including nine in 2020.

The companies usually don’t disclose specific investment amounts for competitive reasons. HorizonX says typical investments in earlier-stage companies range from $1 million to $10 million.

The big three may make investments that are less about a near-term profit, as the executives tell it, and more about advancing technology that could further certain broader strategic goals, either for the corporation itself or for the startups in its portfolio.

Boeing’s HorizonX, for example, invests in focus areas ranging from future mobility to autonomous systems, advanced manufacturing and space, similar to Airbus Ventures’ portfolio categories that include autonomy, electrification and materials. Lockheed Martin Ventures lists 10 areas of interest including autonomous systems, robotics, cybersecurity and space.

Venture execs for the big three say they largely prioritize seed-stage companies — startups that may be no further along than a couple of people in a garage with an idea, or who may have reached the point where they’re ready to start going after customers.

“We’ve always taken the mindset of ‘the earlier, the better,’” says Brian Schettler, the new head of HorizonX who replaced Jones. “We want to help mature the technology.”

At Airbus Ventures, Managing Partner Thomas d’Halluin reassures startup founders that an investment is “all about venture capital” — not, as some fear, a “down payment” on a future acquisition.The big three also have added more than aerospace companies to their investment portfolios.

HorizonX invested in C360, an entertainment company specializing in panoramic video of sports events in 2017 because its software can replay massive amounts of video in near-real time.

And in 2015, Lockheed Martin Ventures provided Kampachi Farms, a fish hatchery operator since renamed Ocean Era, with satellite communications technology in exchange for an equity stake.

Who you are counts

The investors say that once they’re interested in a startup, they place a lot of weight on the founders’ expertise, leadership skills, business sense and reliability — even more so than the product they’re pitching.

Then, of course, there is the quality of the business case that startups present — whether they’ve quantified their pitch with research into marketing channels, customers and market trends and how all those things fit together.

“When they haven’t thought through the value proposition, it’s harder to make an investment in those companies,” says Jones, the former HorizonX chief who now gets to practice what he preaches in his new job as general manager for SparkCognition Government Systems. His role there includes attracting investors.

Even when cash isn’t tight, Moran at Lockheed Martin Ventures notices whether founders keep an eye on their cash flow — how often they get behind and need to urgently ask for more:

“After a couple times, you sort of lose confidence in the CEO.”

Aerospace-savvy investors

Sam Stonberg is one of Lockheed Martin’s “venture leads,” someone assigned to scout for startups that can fill unmet technology needs, in his case for Lockheed Martin Space in Colorado. He says there’s a reason many startups would rather accept an investment from a company such as Lockheed Martin Ventures than, say, a tech venture capital firm that might not have aerospace expertise. In terms of non-venture funding, Stonberg has written letters of support for startups applying for Small Business Innovation Research grants from the U.S. government.

“Our money is different in a way,” Stonberg says. It comes with perks, including the expertise of Lockheed Martin’s engineers and managers and the potential to land Lockheed Martin as a customer right away.

Shey Sabripour founded phased-array satellite communications company CesiumAstro in Austin, Texas, in 2017 and raised the company’s first round of capital from Airbus Ventures. He says his counterparts there are “so hands-on” and that they encouraged him to network with other companies in the portfolio for business leads.

Most promising tech trends

When I asked investors to identify what they see as the most promising technology area, most couldn’t settle on one:

Four named autonomy. Two pointed to advances in quantum physics — atoms harnessed for computing or sensing — and two named robotics. Some rattled off urban air mobility and technology to power deep space missions. Two mentioned artificial intelligence, and two brought up space tourism.

“Who doesn’t want to go to space and look down on Earth?” says Anthony Previte, president and CEO of Tyvak Nano-Satellite Systems in Irvine, California, and a board member of the technology investment firm Starsmith.

Staying the course

The temptation to stray from the established plan — to try to add a new product, for example — stalks startups even under the best of circumstances, says Previte.

Tyvak received an investment from Lockheed Martin, but with 160 employees in the U.S. and abroad, Tyvak is no seed-stage startup. A self-described serial entrepreneur, not to mention an expert in ultra-low-frequency radio astronomy, Previte has learned to stay true to the business plan at Tyvak:

“We don’t bother with other things that end up driving costs and driving schedules.”

His fellow Los Angeles-area entrepreneur Jack Somers, a master’s student at the University of Southern California, learned that lesson last April in advice from a mentor in the school’s Iovine and Young Academy, which offers a cross-disciplinary degree spanning design, business and technology.

His company FirstClassFeel created a thick memory foam cover for airline seats with a washable top layer of antimicrobial fabric. Before the pandemic, he already had a U.S. patent and a factory lined up in China to start making the seat covers.

Then, anticipating that people would want to start covering their office chairs, too, he started to work on that idea. But a mentor within the academic program advised him to “stay the course,” instead suggesting that Somers pivot to pitch the seat, both to investors and directly to airlines, as a way to reassure pandemic-anxious travelers.

Timing and the low-cost way in

If the pandemic drags on and investors continue to hold out on the newest startups, you might wonder if it’s even worth trying to start a company right now.

Moran at Lockheed Martin Ventures has a tip: If you don’t have the money to build hardware, start on the software. Cloud computing platforms such as Amazon Web Services have brought the costs of software development way down.

But is it possible that the time’s just not right? Maybe.

“It’s a very complicated set of attributes that all have to be aligned to make successful startups work. You can’t control timing. A great idea at the wrong time won’t be a great idea,” says HorizonX’s Schettler.

“But our no’s aren’t forever no’s,” he says.

“The timing might be right down the road.”