Stay Up to Date

Submit your email address to receive the latest industry and Aerospace America news.

The debut of Jeff Bezos’ New Glenn rocket design vividly illustrated the contrast between Blue Origin’s “step by step, ferociously” approach and the “break it till you make it” philosophy that Elon Musk and SpaceX have embraced for the Starship-Super Heavy vehicles. Cat Hofacker analyzes the competing approaches, their origins and what’s at stake.

Blue Origin’s New Glenn design and SpaceX’s Starship-Super Heavy vehicles are famously competing to open the space frontier to human exploration by NASA and settlement by others, but for Bezos, there is nearer-term potential benefit.

One is a possible shift in market momentum from SpaceX to Blue. “They’ve got the latecomer advantage,” says Chris Combs, an aerodynamics professor at the University of Texas at San Antonio who watches the two programs closely. He’s referring to that quirk of technology development that could permit Blue to master booster landing and reuse more quickly than SpaceX did with its Falcon rockets, by learning from SpaceX’s mistakes. The first Falcon booster landing came on the design’s 20th flight, but Combs predicts that Blue could easily land a booster within 10 flights.

New Glenn’s debut also brings the design a step closer to being certified by the U.S. Space Force to launch large spy and military satellites. SpaceX has enjoyed a near monopoly on these national security launches with its Falcon fleet, but soon the U.S. might find itself with three competitors: Blue Origin with New Glenn, SpaceX with Falcons and United Launch Alliance, whose Vulcan Centaurs were under final certification review by Space Force as of late January.

Blue’s entrance into the competition, as much as anything, demonstrates that SpaceX’s methods aren’t the only way to make an entirely new class of rocket. When the first New Glenn lifted off in the early morning of Jan. 16 at Cape Canaveral and boosted its demonstration payload to medium-Earth orbit, the breakthrough culminated at least 10 years of research and testing without any exploding launch pads or “rapid unscheduled disassembles,” as SpaceX calls vehicle explosions.

Which is not to say that Blue doesn’t know test failures. The company crashed two New Shepard boosters in the years leading up to Jan. 16, but those occurred in the safety of its test range, an uninhabited expanse of desert near Van Horn, Texas.

In New Glenn’s debut, the booster’s data transmission fell silent during its return to Earth, and it did not achieve the hoped-for landing on the recovery barge, Jacklyn, named for Bezos’ mother. The barge sailed home empty to Port Canaveral from the Atlantic Ocean, north of the Bahamas.

The contrast in developmental approaches was vividly demonstrated 15 hours later, when the seventh Starship-Super Heavy lifted into the afternoon sky from Boca Chica, Texas, on a mission to test the first Block 2 Starship, a revised upper stage. With larger propellant tanks and other upgrades, this Starship was supposed to be the first one to deploy payloads, specifically, 10 simulated Starlink satellites that like Starship would be placed on suborbital trajectories. Instead, SpaceX lost contact with the ship roughly 8 minutes into the flight, and within an hour, videos on social media showed debris streaking earthward over the Turks and Caicos Islands. FAA said later that it diverted dozens of flights and was “working with SpaceX and appropriate authorities to confirm reports of public property damage.” In the following days, multiple photos and videos on X showed what appeared to be chunks of Starship on beaches and a golf course.

The Super Heavy booster, though, headed back to the pad and lowered itself to achieve the second “chopstick” capture by the launch tower. Such is spaceflight: New Glenn reached orbit, but its booster was lost. Starship did not reach orbit, but its booster made it back intact.

Musk shrugged off the latest Starship loss, joking on X: “Success is uncertain but entertainment is guaranteed!”

For him, the loss of the vehicle was not a failure but a quick way to find out if there was a problem with the upgraded design so that it could be fixed. Musk followed up on X to say that early analysis pointed to “an oxygen/fuel leak in the cavity above” Starship’s six Raptor engines that caused a fire.

For Blue Origin, based in Kent, Washington, New Glenn’s drama-free deployment vindicates its “gradatim ferociter” — “step by step, ferociously” — slogan that encapsulates its approach to technology development. Blue decided early on to master suborbital flight with a vehicle one-fifth the size of New Glenn. The start was rough. The first New Shepard rocket, an unoccupied vehicle, crashed during its inaugural flight in April 2015. But on the second try seven months later, Blue launched and landed the booster and its unoccupied capsule. It then repeated that feat 14 more times before launching its first passengers in 2021.

As of early February, Blue has launched New Shepards 29 times and landed the booster in all but two of those flights. In both cases, engine issues caused a loss of control. New Glenn’s debut showed that Blue has yet to master the technique at a much larger scale.

As different as the approaches of Blue and SpaceX are in terms of risk acceptance, they are both examples of iterative design, in which products are incrementally refined, says Combs, the aerodynamics professor.

“What’s novel about the SpaceX approach is they’re much more willing to do full-scale iterative design,” he says. “You can collect a lot of data that way. You can learn a lot of things.”

However, he adds, blowing up dozens of multimillion dollar vehicles is “a real luxury that very few organizations can actually afford. When you’re backed by the richest person in the world, that helps.”

Of course, Bezos is the second richest, so in theory, Blue could choose to do the same but has not.

The Starship explosion has had literal and figurative fallout: Musk’s “‘fail and fail often’ philosophy isn’t bold innovation — it’s reckless disregard for the planet and its people,” wrote Moriba Jah, an astrodynamicist and Aerospace America columnist, in a LinkedIn post. “This attitude reeks of arrogance and privilege, especially when the failures of these ventures, often framed as learning opportunities, come at the expense of the environment, public safety, and global livelihoods.”

SpaceX did not respond to requests for comment, but a portion of the company’s post-launch statement posted on its website seemed aimed at addressing such public safety concerns: “Starship flew within its designated launch corridor — as all U.S. launches do to safeguard the public both on the ground, on water and in the air. Any surviving pieces of debris would have fallen into the designated hazard area.”

While SpaceX often describes its approach as the best way to quickly make progress, that might not always hold true. Combs notes that Blue Origin’s version of iterative design requires a longer development stage, but “it can potentially be more efficient” in the long run. “If things go well with the full-scale flight testing and things work within the first handful of tries, it’s going to be way faster to go that way.”

He notes that a Starship has yet to attempt to complete an orbit of Earth. All seven Starship-Super Heavy flights have followed suborbital trajectories so that SpaceX can practice and refine landing techniques for both stages, among other objectives. Three Starship upper stages have made controlled splashdowns in the Indian Ocean, and two Super Heavys have flown back to the launch site for capture in the tower’s chopstick arms.

Shortly after last month’s flight concluded, FAA ordered SpaceX to investigate the loss of Starship and provide a report describing “corrective actions” that must be completed before the next vehicle flies. This is the design’s fourth grounding. Blue, due to the loss of the booster, must also complete a mishap investigation and submit a report to FAA to receive its launch license for New Glenn’s second flight. Blue says it’s targeting “spring” for that launch. Ever optimistic, Musk said on X that he believes the next Starship could be launched in February.

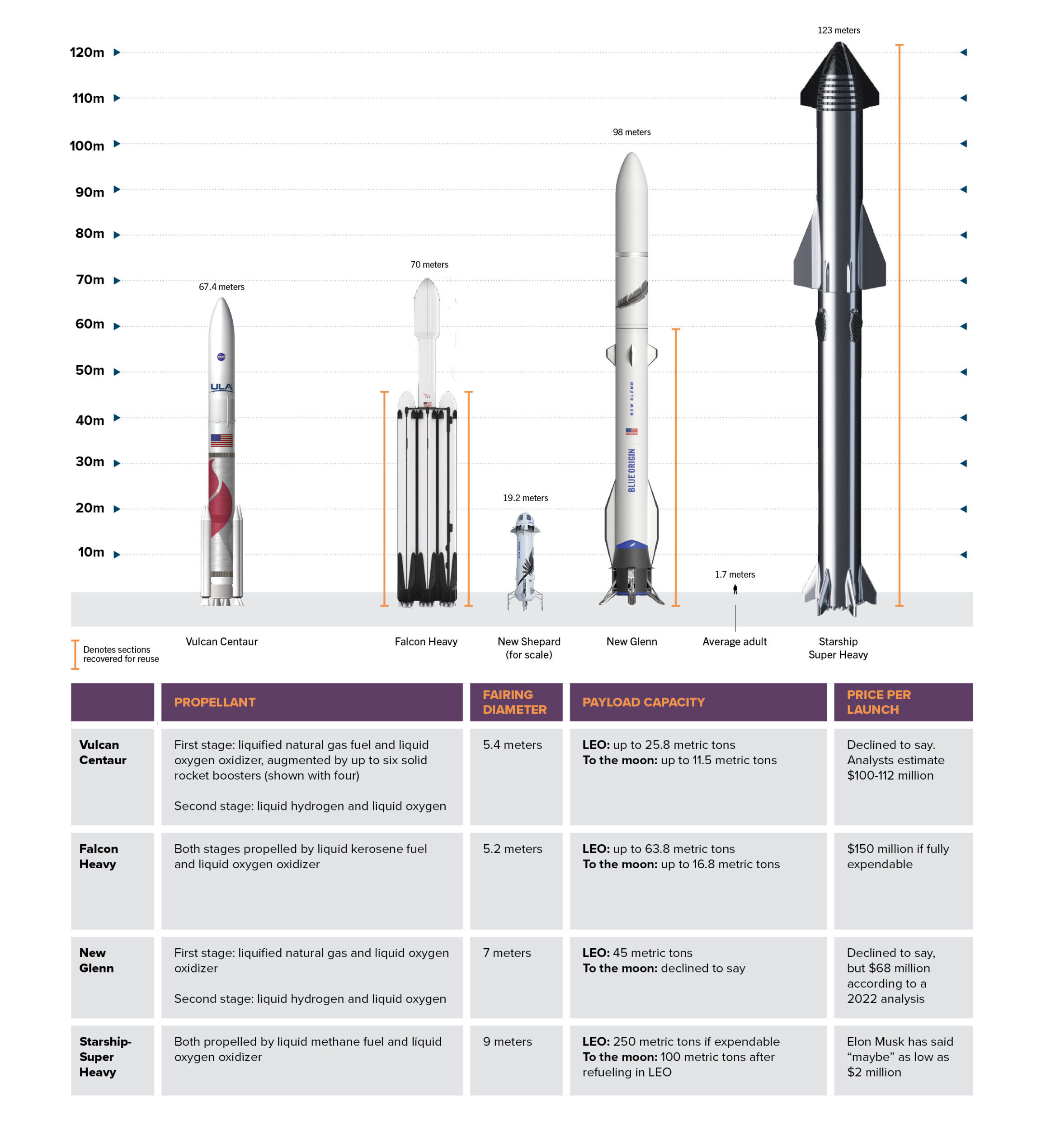

Though there is heady competition between Blue and SpaceX, the two rockets are not equally matched in payload capacity. New Glenn is targeting 45 metric tons — double what Falcon 9 can send to low-Earth orbit but less than Falcon Heavy’s 64 metric tons. Starship would dwarf them all, with its 9-meter-diameter fairing designed to carry 100 metric tons in reusable mode, and up to 250 in expendable.

But until Starship begins commercial operations, New Glenn’s 7-m-diameter fairing may be the best option for customers whose spacecraft don’t fit in the roughly 5 m fairings of Falcons and ULA’s Vulcan Centaurs, or who are looking to launch more spacecraft at a time.

In the near term, Blue has contracts to launch satellites for commercial megaconstellation builders in addition to competing for the national security launches. Longer-term plans call for ferrying cargo and NASA astronauts to the moon under the Artemis program. At this writing, Starship’s advertised roles are to launch Starlinks, deliver astronauts and cargo to the moon for NASA, and someday fulfill Musk’s dream of sending 100 people at a time to Mars. SpaceX hasn’t said if it will submit Starship for national security missions, but the U.S. Space Force is reportedly interested in studying how the design might be used to ferry large amounts of cargo.

Despite their many differences, New Glenn and Starship share an emphasis on reusability. That feature is partly tied to affordability, but it’s also driven by the personal ambitions of the company founders. Bezos proposes creating colonies in low-Earth orbit where millions would live and work, and Musk frequently talks about establishing a “self-sustaining” city on Mars. Both visions require the ability to frequently launch large amounts of crew and cargo in one go. Rockets designed to launch and land over and over would be the best way to achieve this.

Of course, with Blue’s “slow and steady” pace also comes increased expectations from customers, says Ryan Puleo, an analyst with Virginia-based BryceTech. Indeed, up until this point, development of New Glenn was more step by step than ferocious. The debut was originally scheduled for 2020 but was repeatedly delayed, partly due to challenges in developing the BE-4 booster engines. Those delays were compounded by Blue’s contractual obligation to deliver the first BE-4s to ULA for the Vulcan boosters. However, this brought a small upside: ULA launched two Vulcans in 2024, allowing Blue to see the BE-4s in action before New Glenn’s flight.

If past is prologue, that extended development phase could recede quickly into memories, if Blue concludes the investigation and is permitted to return to flight expeditiously. Hardly discussed today are the three extra years it took to achieve New Shepard’s first passenger flight, the 2021 flight to the fringes of space with Bezos and three others.

James Muncy, a Virginia-based space consultant, welcomes the arrival of a “competitive marketplace” but cautions against trying to judge each company’s approach against the other. “We’ll find out what works, and what works for one of them probably wouldn’t have worked for the other, and vice versa.”

The heavy-lift competitors

A customer who needs to launch more than 20 metric tons to orbit — the equivalent of three James Webb Space Telescopes — could soon have three rocket designs to choose from. Once fully certified, New Glenn and ULA’s Vulcan will compete against SpaceX’s Falcon Heavy to launch U.S. spy and military satellites. NASA is counting on New Glenns and Starships for its Artemis lunar landing program.

About cat hofacker

Cat helps guide our coverage and keeps production of the print magazine on schedule. She became associate editor in 2021 after two years as our staff reporter. Cat joined us in 2019 after covering the 2018 congressional midterm elections as an intern for USA Today.

Related Posts

Stay Up to Date

Submit your email address to receive the latest industry and Aerospace America news.