Stay Up to Date

Submit your email address to receive the latest industry and Aerospace America news.

Engine design will be key to reviving commercial supersonic air travel in a way that is affordable and environmentally palatable. After a setback in September, Colorado-based Boom Supersonic believes it now has the right engine team and approach. Aaron Karp tells the story.

Anyone on hand when British Airways flight BA002 touched down in London in October 2003, bringing an end to the Concorde era, would have seen a design and clientele far different than those planned today by Boom Supersonic. The well-financed Colorado company is attempting to lead the industry back into the business of supersonic air travel, this time hopefully for good. The Concorde’s nose, as always, was drooped forward during landing and taxiing to permit the flight crew to see. Once on the tarmac, its four Rolls-Royce/Snecma Olympus 593 engines spooled down. Among the passengers who disembarked were, reportedly, model Christie Brinkley, actress Joan Collins, talk show host David Frost and journalist Piers Morgan, then the editor of the Daily Mirror newspaper.

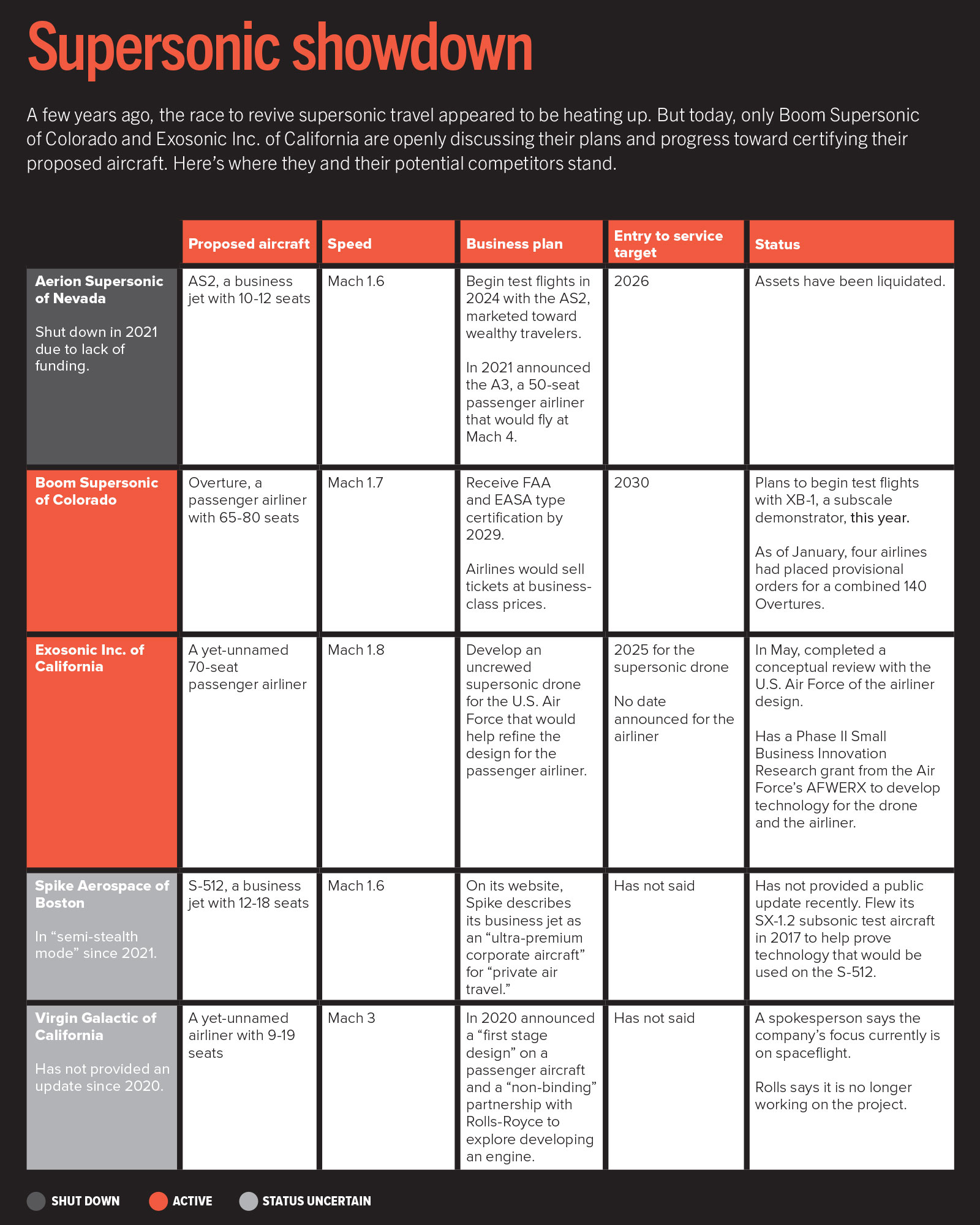

By contrast, Boom Supersonic and its startup competitor Exosonic Inc. of California are targeting not the rich and famous, but those willing to pay business class prices. In fact, the demise of the Concordes has often been blamed largely on an overreliance on wealthy consumers. Each aircraft’s immense operational costs, driven by high fuel burn, meant even extraordinarily high fares could not make them profitable. On top of that, the confidence of travelers was shaken when an Air France Concorde crashed on takeoff from Paris in 2000, killing all 109 aboard and four on the ground.

Exosonic has established a much longer timeline than Boom, which means that dreams of reviving supersonic air travel anytime soon hinge on the new team that Boom has assembled to create a “clean sheet” engine that will operate with acceptable maintenance costs and provide carbon neutral thrust by burning 100% sustainable aviation fuel made from replenishable sources rather than fossil fuel. Plans had called for Rolls-Royce to adapt an existing engine design, but in September, Rolls confirmed in media reports that it would no longer participate in the project. This prompted Boom to announce the new team in December and give the proposed engine a calming name: Symphony. Four Symphonies are to propel each of Boom’s planned Overture jets.

“As Boom has matured the Overture program, we listened to our partners and customers and learned that applying the current subsonic engine model to our supersonic airliner would not be the most economically sustainable solution,” said Troy Follak, senior vice president of Boom’s Engineering and Program Office, by email. “By developing a new engine, Boom can provide significant savings and benefits for airlines and passengers.”

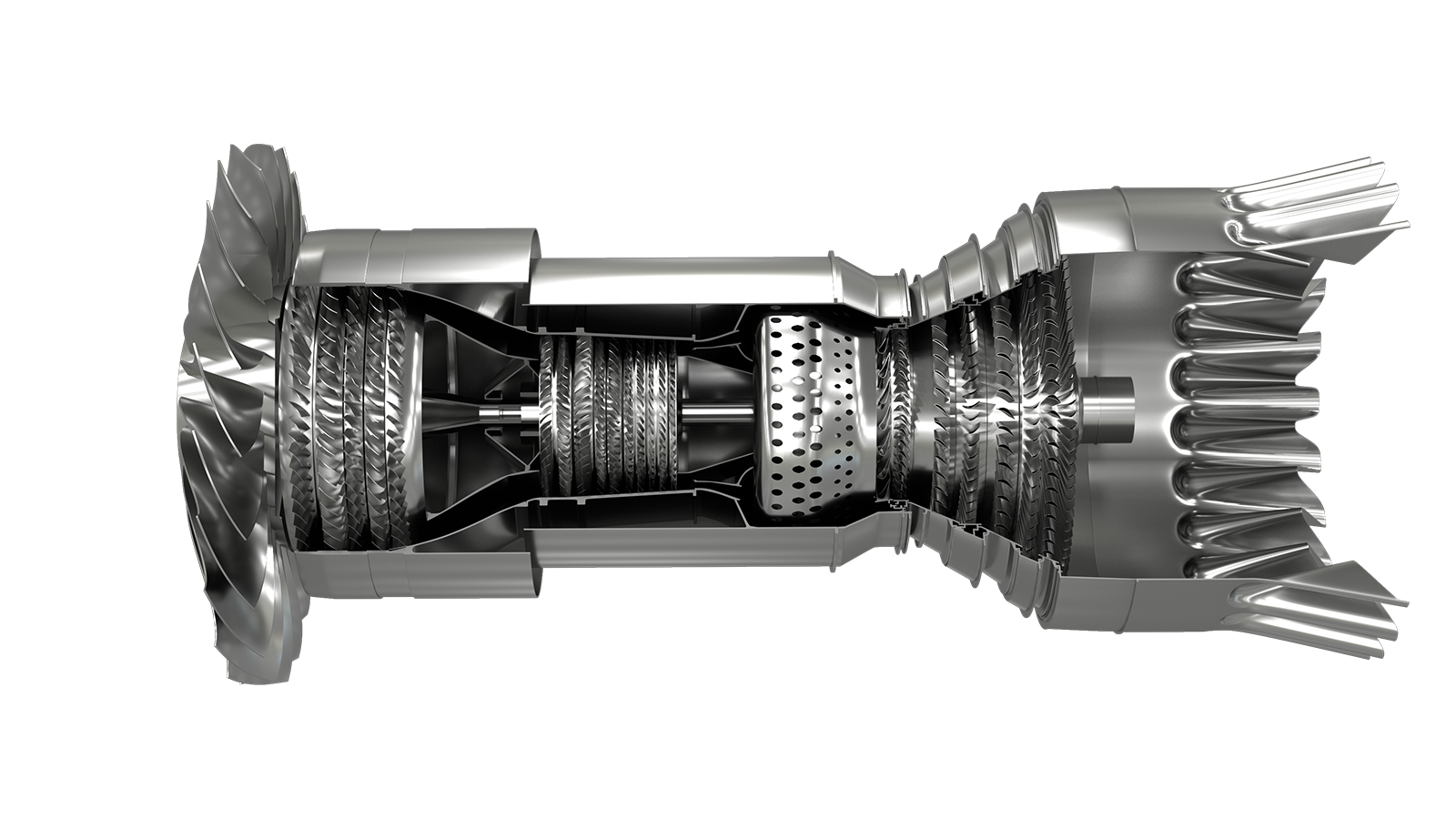

The team’s makeup is unconventional compared to past engine efforts: The engine will be designed by Florida Turbine Technologies, the unit of Kratos Defense and Security Solutions that helped design the engines for the U.S. Air Force’s F-22s and multiservice F-35s; GE Additive of Cincinnati will provide advice about 3D printing components; and StandardAero, an aviation maintenance company in Scottsdale, Arizona, has the task of making sure the Symphony engines will be maintainable.

Symphony will be a twin-spool, medium-bypass turbofan engine producing 155,693 newtons (35,000 pounds) of thrust. Overture is being designed to fly at Mach 1.7, slower than the Concorde, which could reach speeds just over Mach 2. Even so, when or if Overtures fly, passengers will be able to get from New York to London in 3.5 hours and from Seattle to Tokyo in 4.5 hours, Boom says.

Given the Concorde’s history, affordable flying is a top priority for Boom. A Concorde flight ticket typically exceeded $10,000 during the fleet’s 1976 to 2003 in-service lifespan. Most Americans and Europeans could only fantasize about enjoying high-speed trans-Atlantic travel. Boom expects its planned Overture aircraft, at least in their initial years of operation, to have fares of $1,000 to $2,000, in line with today’s long-haul business-class ticket prices. Boom is aiming for an operating cost that’s 75% less compared to the Concorde.

As for the timeline, Boom believes that it can develop the new engine in time to conduct the first Overture test flight in 2027 so the aircraft can be certified by 2029 by FAA and EASA, the European Union Aviation Safety Agency. Airlines could then commence commercial flights in 2030.

Is that schedule feasible? Chris Combs, an assistant professor and expert in high-speed aerodynamics at the University of Texas at San Antonio, calls it “ambitious” and the schedule “aggressive.”

Like Exosonic, another developer is taking a slower approach. Though there is “exceptional hype in the race to be first,” it will take time “to reintroduce supersonic flight that is responsible, quiet, fuel-efficient and environmentally sound,” said Max Kachoria, CEO of Spike Aerospace, by email. The Boston company has been in semi-stealth mode since 2021 and has not announced a target date for its Mach 1.6 business jet, which has been in development for almost a decade.

He added that “too often the first to market introduces a minimally viable product.”

Long shadow

The U.S. general public’s early experience with supersonic flight was the loud sonic booms generated by military jets. In 1968, with the Concorde on the verge of achieving first flight, Congress directed FAA to “prescribe and amend standards” for aircraft noise and sonic booms. This led to the agency’s 1973 ban on civil supersonic flight over land — a serious impediment to the success of the Concorde, then still in the midst of flight testing. Only 20 were ever built by France’s Aerospatiale and the British Aircraft Corp., the British-French joint venture that developed the aircraft in the 1960s. Concorde made its first test flight in 1969, the same year as the moon landing, a heady time for achievement in flight. Six of the 20 Concordes were devoted to the five-year test flight program and only 14 were ever operated by airlines — seven each by British Airways and Air France.

After the Air France crash, both fleets were grounded by regulators for more than a year. The Concordes returned to service in November 2001, but matters from there unfolded more like a denouement.

Today, freeing themselves from Concorde’s shadow remains a top priority for Boom and Exosonic. Each company says its new aircraft will be quite different from the original.

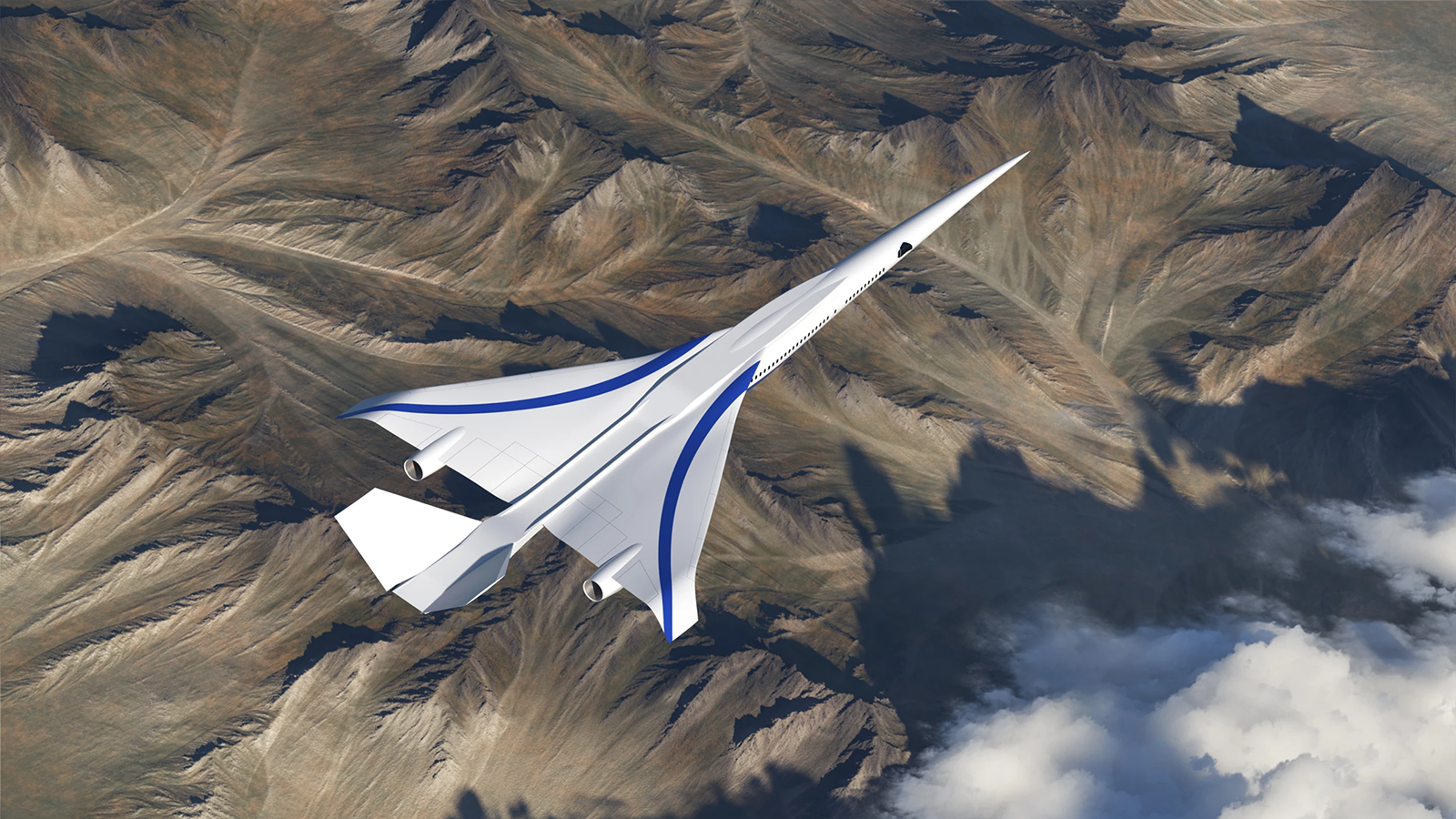

For Boom, that means constructing Overtures out of carbon composites instead of aluminum. Overture’s wingspan will be 7 meters longer than Concorde’s (32 meters versus 25 meters), with a gull wing design that has a curved inner section, a subtle contrast to Concorde’s delta wings. A more noticeable difference: Overture’s pointed nose will remain so during takeoff and landing in a departure from the famous “drooped nose” designers adopted to maximize pilots’ visibility on the Concordes. Boom says that particular feature made the aircraft heavier and likely extended the certification process, so it instead plans to design Overture with a “virtual forward window” via external cameras. The company is testing this artificial vision system on its subscale demonstrator, XB-1, affectionately nicknamed “Baby Boom.”

A number of airlines appear to believe in the future of supersonic flight, contending there will be demand among the public for super-fast airline trips. American Airlines, Japan Airlines, Virgin Atlantic Airways and United Airlines have all placed provisional orders for the Overture, with American taking the step of paying a nonrefundable deposit in August on 20 aircraft. The airline declined to specify the dollar amount of the deposit when I asked.

Fresh approach

In an unconventional twist, none of the big three aircraft engine manufacturers — General Electric’s GE Aerospace, Pratt and Whitney, and Rolls-Royce — will be involved in the Symphony program. Rolls backed out after two years of research cooperation toward a potential engine.

“After careful consideration, Rolls-Royce has determined that the commercial aviation supersonic market is not currently a priority for us and, therefore, will not pursue further work on the program,” Rolls said in a statement in response to my inquiry.

Rolls and France’s Snecma jointly produced the Olympus 593 engine that powered the Concorde.

Boom, for its part, says its research with Rolls led it to the conclusion that a derivative of a current in-service engine was not viable. That said, Boom says the envisioned “clean sheet” engine will borrow technology and design elements from currently operated commercial aircraft engines.

Follak, the Boom executive, underscored that this won’t be a vendor arrangement: Boom will “have full control and ownership of the design” for the engine.

GE Additive’s involvement could signal that GE Aerospace, the parent of the unit, might take a bigger role in the Symphony program in the future, though this is far from certain.

“There are not that many companies in the world that produce commercial jet engines that run on passenger aircraft,” says Combs, the assistant professor. “There’s a reason for that — it’s really hard to do.”

But he does believe FTT, as Florida Turbine Technologies is known, could very well succeed, even if he questions the timeline.

“They’ve got an interesting team they’ve put together and a lot of smart people who know a lot about aircraft engines, so I think they’re capable. But even in a best, best-case scenario, the timeline is ambitious and it’s going to take them a while,” Combs says. “Four years would be a really, really short amount of time to get this engine tested and integrated onto an airframe and then actually up in the air” for a first test flight in 2027.

Boom’s competitor Exosonic appears to agree. The company firmed up its supersonic aircraft design in early 2022, but has shifted its focus to first developing a supersonic drone, targeted to begin flying in 2025. When I asked about this slower approach to passenger transport, Exosonic CEO Norris Tie cited the lack of interest by the major manufacturers in developing an engine.

A new commercial supersonic engine is “10-plus years away,” says Tie.

Overland challenge

It’s tempting for designers to count on beginning the acceleration toward supersonic speeds by injecting fuel into each engine’s hot exhaust, but these afterburner mechanisms are loud. Concorde’s Olympus 593 engines each had an afterburner. NASA’s X-59 supersonic test aircraft has one on its single GE Aerospace F414-GE-100 engine, a design similar to those on U.S. Navy FA-18E Super Hornets. Installation of that engine was completed in November in preparation for the first X-59 flight, planned for later this year.

The point of the X-59, however, is not to prototype a commercial supersonic design or even to demonstrate low engine noise. The goals are to show that a sonic boom audible to people on the ground can be averted through design tweaks and find out if the resulting “sonic thump” will be tolerable to residents. To find out, a NASA pilot will steer the X-59 overland at a high altitude, too high, in fact, for engine noise to be heard on the ground. The shockwave at the front of the aircraft will be minimized by smoothing the cockpit with the nose, while an “aft deck” at the tail end “reflects shock waves from the engine exhaust upwards, thus preserving the low boom signature that travels to the ground,” explained Craig Nickol, NASA’s senior adviser for integrated aviation systems, via email.

If things go as hoped, international and national regulators will see the X-59 results and lift the current ban on overland supersonic flight, provided the aircraft make only a sonic thump.

Regarding the afterburner, Nickol said X-59 will be “operating on an experimental basis from installations that can accommodate” higher takeoff noise. “In addition, the X-59 may not require the afterburner for takeoff depending on the particular operating conditions present,” he says.

James Bridges, NASA’s airport noise tech lead on the Commercial Supersonic Technology program, added via email: “Bottom line, commercial supersonic transports will not be able to use afterburners during takeoff and landing because they would be so loud.”

No one has to convince Boom that afterburners are undesirable. “One major difference from 1970’s-designed supersonic engines is that the Symphony engine enables supersonic flight without afterburners, which make military supersonic aircraft notoriously noisy,” Boom’s Follak said, noting that the Concorde’s engines “were not designed to meet the emissions or noise requirements” of modern commercial aircraft.

He added: ”The engine has a Boom-designed axisymmetric supersonic intake, and a variable-geometry low-noise exhaust nozzle that efficiently combines the hot exhaust air with the cooler bypass air and varies the exhaust area to match subsonic and supersonic thrust requirements,” and that should allow for takeoffs that do not create an airport noise problem.

For Boom, it’s the boom that could emerge as the biggest hurdle. Without the ban being lifted, Overture could have difficulty gaining as much traction as Boom would like. Routes such as New York to Los Angeles would be off the table, and routes such as Chicago to Amsterdam would require the aircraft to fly at subsonic speeds for the parts of the journey that are over land.

While less than ideal, that’s the scenario the company is planning for. “When flying over land, Overture will fly at a high subsonic speed that is about 20% faster than current commercial aircraft” without producing a sonic boom, Follak said.

Even with these limitations, Boom is projecting it can sell 1,000 to 2,000 Overtures to airlines, which means many more routes than the limited trans-Atlantic Concorde lineup operated by British Airways and Air France. “In total, there are more than 600 mostly transoceanic routes on which Overture offers a compelling speedup without changes to today’s overland flight regulations,” Follak said. “What I can tell you is that we expect that North America to/from Europe will see robust demand for Overture flights.” He added that the company also sees trans-Pacific opportunities and potential routes between the Middle East and Asia.

Boom has also promoted the possibility of a “same day” trans-Atlantic trip, in which a New York businessperson returns from London following a midday meeting and, with the time change, is able to sleep at home that night.

But in the long term, data gathered from the X-59 flights “hopefully paves the way for the FAA loosening some restrictions on overflight of land,” Combs says.

One conviction is widely shared: A new supersonic jet would be vastly different from the Concorde, though this is no guarantee the aircraft will be commercially viable.

“The Concorde was developed in the 1960s, and we’re now in 2023,” Tie of Exosonic says. “There’s been a lot of advancement. And so I think there are some general industry-wide savings you’ll get in terms of performance and cost and weight” that wouldn’t have been possible with the Concorde.

Despite the hurdles, Combs believes a new era of supersonic flight will happen. “I think there’s enough momentum that I’m very confident we will see supersonic passenger flights in the future,” he says. “When that happens, and who it is, that I’m not as confident about.”

About Aaron Karp

Aaron is a contributing editor to the Aviation Week Network and has covered the aviation business for 20 years. He was previously managing editor of Air Cargo World and editor-in-chief of Aviation Daily.

Related Posts

Stay Up to Date

Submit your email address to receive the latest industry and Aerospace America news.