Stay Up to Date

Submit your email address to receive the latest industry and Aerospace America news.

The aviation industry once treated all hackers as threats, even those who sought a bit of fame but not necessarily fortune by publicly demonstrating vulnerabilities without causing damage. Debra Werner says the industry’s view of these hackers is changing.

Patrick Kiley was in Florida for a cybersecurity training conference in 2017 when he stopped by the Sun ’n Fun Aerospace Expo, the vast annual gathering of aircraft buffs in Lakeland. At home in Las Vegas, Kiley was building a four-seat variant of the Long-EZ, a two-seat kit airplane design from the Rutan Aircraft Factory. He stopped to listen when he met some fellow homebuilt aircraft aficionados who were talking about linking their various onboard electronics with CAN bus, a standard common among mechanics for wirelessly linking microcontrollers and devices within a vehicle.

As a self-described “car hacker” and principal security consultant for cybersecurity firm Rapid7, Kiley knew that the Controller Area Network bus required no authentication, meaning anyone with physical access could take control of the steering wheel or brakes. He wondered if CAN bus would make planes similarly vulnerable to cyberattack.

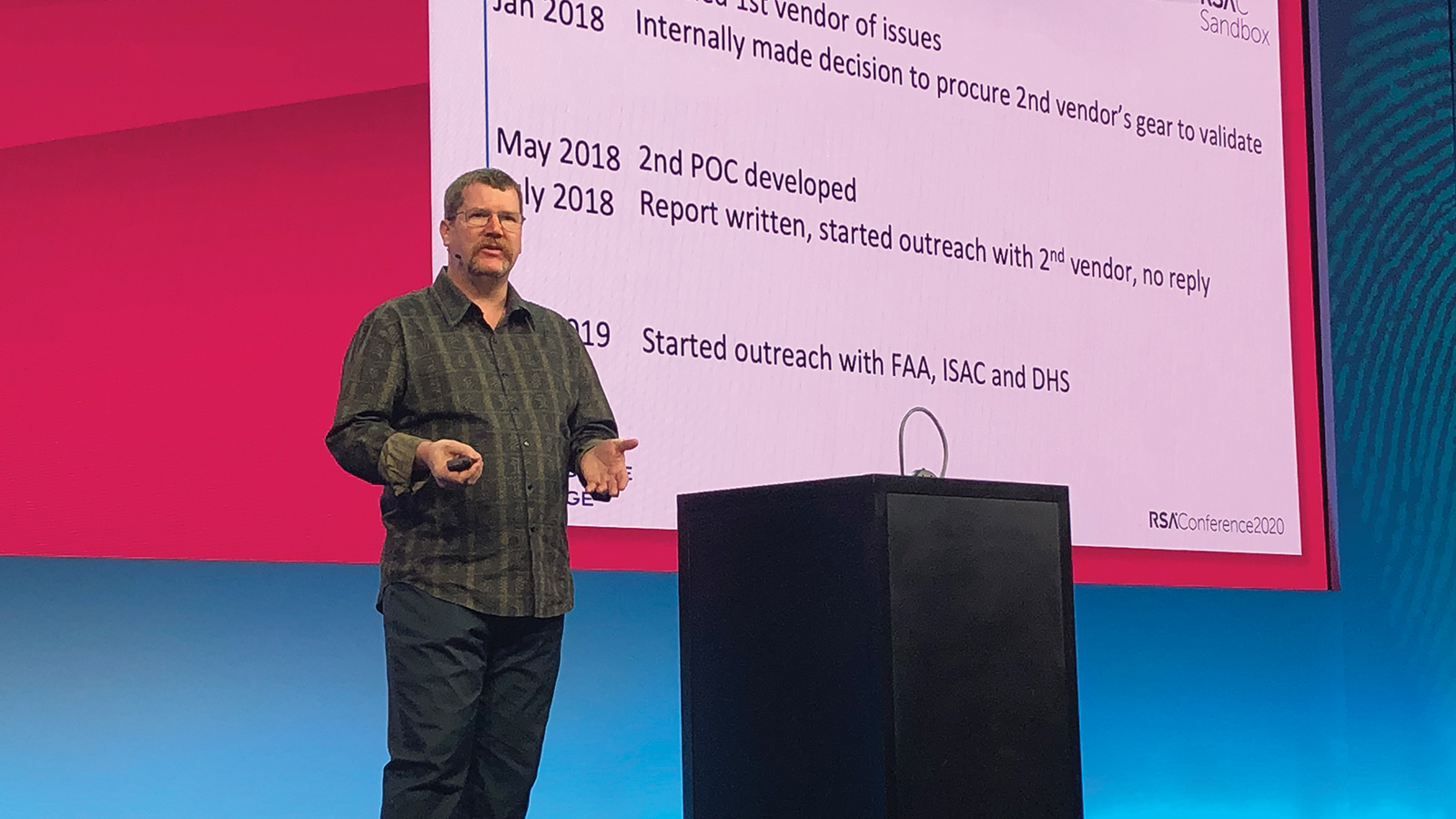

To find out, Rapid7 bought avionics from two vendors Kiley declines to name and he quickly discovered he could cause all sorts of trouble. He introduced commands to turn off the autopilot. He changed engine telemetry readouts.

Rapid7 and Kiley spent more than a year discussing his findings with an avionics vendor, FAA, the Department of Homeland Security, and the Aviation Information Sharing and Analysis Center, or A-ISAC, the international membership organization based in Maryland. He also presented his work in 2019 at Defcon, the convention in Las Vegas that typically attracts 20,000 hackers of all stripes.

If the word “hacker” makes you think of somebody under a figurative black hat trying to steal intellectual property or hijack planes, that’s one kind of hacker, but that’s not who Kiley and others interviewed for this article are. They are paid cybersecurity researchers with boundless curiosity and a knack for finding flaws in software or computer networks. Some could be called gray hats when their research isn’t authorized by the organizations they investigate. Others work primarily as ethical hackers, called white-hat hackers, who are hired by an organization to look for vulnerabilities.

“The analogy I draw is to a car guy, somebody who knows everything about 1960s muscle cars, can take an engine apart in a weekend and put it back together with extra horsepower,” says Brad Haines, who’s known in the hacker community by his high school nickname RenderMan, after the Pixar animation software.

Leveraging hackers’ knowledge

For a long time, aviation companies and government agencies had little contact with hackers whose scrutiny of networks was not invited. That’s beginning to change.

“If we are going to secure this industry, we basically need the help and involvement of everybody,” says Remzi Seker, founder and former director of the Cybersecurity and Assured Systems Engineering Center at Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University in Florida. “If a group of hackers wants to help, then the industry needs to look into how we can leverage these people, their energy, their knowledge and their time.”

The aviation establishment is listening. The United Nations’ International Civil Aviation Organization encourages its member countries to “set up appropriate mechanisms for cooperation with ‘good faith’ security research.”

The Atlantic Council think tank in Washington, D.C., conducted a survey last year and found “strong agreement that good-faith researchers were a positive thing for the aviation industry.”

Still, it’s not an easy alliance. In the past, hackers felt like aviation companies and government agencies kept them at arm’s length privately while publicly dismissing their research. Aviation equipment manufacturers, meanwhile, complained hackers sometimes made exaggerated claims about their ability to breach networks that undermined public confidence in aviation safety.

A little over a year ago, a group of security researchers, pilots and aerospace industry executives created a nonprofit international organization to bridge that divide. They called it the Aviation Village since Defcon is split into villages where attendees delve into various topics, such as automotive cybersecurity. They later renamed their group the Aerospace Village to underscore aviation’s growing reliance on satellites for communications and navigation.

The Aerospace Village is a virtual entity with no physical headquarters. In conference presentations and private meetings, Aerospace Village speakers encourage collaboration and communication with hackers.

“We need to get past stereotypes of the sinister masked hacker or the guy living in his parents’ basement so we can find problems and make flying more safe and secure,” says Steve Luczynski, a member of the village’s board of directors and a former U.S. Air Force fighter pilot. He is now chief information security officer at T-Rex Solutions, an information technology company in Maryland.

New vulnerability

Airplanes were once cut off from ground-based computer networks after takeoff, meaning someone needed physical access to interfere with avionics. Now, airplanes share data in flight with multiple ground networks to get a head start on maintenance needs, offer passenger entertainment and announce their locations.

“An aircraft is pretty much a computer that happens to have wings, two engines and people in the front flying it,” says Pete Cooper, Aerospace Village director and a former British Royal Air Force jet pilot who advised the United Kingdom’s Ministry of Defense on cybersecurity. “When I’m talking to airlines, I’m trying to get across the message that their aircraft are as much a part of their enterprise architecture as their offices.”

Hackers notice the similarity and see planes “as connected devices,” says Haines, aka RenderMan.

Haines attracted attention in the aviation world when he gave a talk in 2012 at Defcon about spoofing the outgoing position and identity signals from the FAA-required Automatic Dependence Surveillance-Broadcast transponders on aircraft to give the appearance of more planes flying in an area.

“Hackers are passionate about the craft,” Haines says. “When people say a system is secure and protected, if I can find a way to defeat it, I’ve literally done the impossible. That’s kind of cool, and if I can figure out how to defeat it, maybe somebody else can, too.”

Haines says he wanted to share his research with aviation companies because he flies a lot and “a certain amount of self-preservation was involved” but he “couldn’t figure out how to report it to anyone, so I dropped a bombshell.”

Chris Roberts, who was escorted by FBI agents off a United Airlines flight in Syracuse, New York, in 2015 after tweeting about hacking the plane, tells a similar story. Roberts spent years gathering flight manuals, studying wiring diagrams and testing components in his home laboratory to discover vulnerabilities in airplane networks. He says he found troubling links between the in-flight entertainment system on Airbus and Boeing planes and other onboard networks, including flight controls. He says no one took his warnings seriously until his 2015 tweet suggesting he could access the plane’s Engine Indicating and Crew Alerting System and release passenger oxygen masks.

“Companies would rather spend money on lawyers and public relations to deny the issue rather than bringing in an outsider to help fix a problem,” Roberts says.

Now, the Aerospace Village, Airbus, Boeing and A-ISAC are inviting hackers to share their findings.

At Defcon in 2019, the U.S. Air Force invited hackers at the Aviation Village to break into an F-15 fighter jet’s Trusted Aircraft Information Download Station, a device that collects video and sensor data. At 2020’s Defcon, which will be online due to the covid-19 pandemic, the Aerospace Village will host Hack-a-Sat, a contest to see who can identify security flaws in an Air Force satellite.

Airbus and Boeing invite researchers to email encrypted summaries of their findings. On its website, Airbus asks researchers to email “a brief description of the issue identified, including what was attempted and the result” to [email protected]. “If you are able to provide additional information regarding the affected Airbus product, service or offering, it will also be beneficial for our investigation.”

At Boeing, email sent to [email protected] “gets routed to my organization,” says John Craig, Boeing Commercial Airplanes chief engineer for aviation networks and security and A-ISAC board chairman. “These third-party researchers are trying to understand how aviation works. We came to the realization that it is in our best interest to reach out to these folks and see how we can get a responsible interaction on aviation security issues.”

In addition, the A-ISAC helps security researchers make contact with companies to ensure responsible disclosure, meaning researchers share information with industry chief information security officers and give companies time to patch software or otherwise shore up network vulnerabilities before making the information public, says Jeffrey Troy, A-ISAC president and CEO.

Giving hackers credit

How and when hackers publish their research is often a sticking point in discussions with companies or government agencies.

Kiley, the CAN bus researcher, spent months seeking approval to publish his findings.

“After many, many back-and-forth conversations with the FAA, the A-ISAC, DHS and one of the vendors, we did the release of the report,” Kiley said at the RSA cybersecurity conference in San Francisco in February. “We delayed long enough to make sure that all the industry partners, the airlines, the airframers and everyone involved was aware of this issue.”

Aviation experts say those delays are essential because aircraft take a long time to fix. Any potential fix has to be certified by government agencies to ensure the aircraft remain safe to fly, said Ken Munro, partner and founder of Pen Test Partners of Buckingham, England, at the RSA conference.

In the hacking community, the lines between hackers who specialize in accessing computer networks without authorization and penetration testers are often blurred. In reality, there are quite a few gray hats, people who do both, or start out as black hats before earning a living as white hats. Haines’ Linked-In profile, for example, says, “Hacker by birth, security professional by trade.”

“Many companies are approached routinely by gray-hat hackers who found vulnerabilities in systems,” says Lisa Sotto, a New York attorney who chairs the Global Privacy and Cybersecurity practice at law firm Hunton Andrews Kurth LLP. “They expect direct payment for information, or they ask to be retained by the company for their expertise.”

If companies can’t afford to pay hackers for their work, they simply offer kudos or acknowledge their efforts. In those cases, according to RenderMan, hackers still come forward, “because notoriety is our bread and butter, very much like publishing for a scientist.”

All of this raises the question of legality. Isn’t trespassing in a private or government network illegal?

It is illegal if hackers are intentionally intercepting electronic communications but not if they stop right before they cross the line. It’s like saying, “I see that there’s no lock, I see that the door is ajar, but I’m not walking in,” Sotto says.

The type of research the Aerospace Village promotes is far removed from day-to-day operations of airlines and airport networks. Instead the Aerospace Village is encouraging researchers to buy aviation equipment and test it in laboratories.

“We would like to see researchers and manufacturers partnering together to leverage the expertise each brings and advance aviation cybersecurity to protect passengers,” says Cooper, the Aerospace Village director who runs Pavisade, a cybersecurity consulting firm in London. “It is fantastic that we are gradually starting to see this happen, but it’s definitely a journey, as manufacturers see the benefits of working with the research community and researchers start to engage and build trust.”

“An aircraft is pretty much a computer that happens to have wings, two engines and people in the front flying it.”

Pete Cooper, Aerospace Village

About Debra Werner

A longtime contributor to Aerospace America, Debra is also a correspondent for Space News on the West Coast of the United States.

Related Posts

Stay Up to Date

Submit your email address to receive the latest industry and Aerospace America news.