Stay Up to Date

Submit your email address to receive the latest industry and Aerospace America news.

If the United States figures out how to shoot down missiles from space, will adversaries throw up their hands and stop making weapons? Or will they simply make more missiles? Jen Kirby digs into the Golden Dome plan.

Imagine that tensions between the United States and a nuclear-armed adversary are intensifying. The threat of an all-out strike against the U.S., by miscalculation or intention, increases by the day.

Suddenly, U.S. satellites equipped with infrared cameras detect the flame exhaust from dozens and dozens of intercontinental ballistic missiles. Those tracking satellites summon the nearest interceptor carrier satellites, like the algorithm of a ride-hailing app finding the nearest driver. Interceptor rockets are fired off, and they accelerate to ram into the missiles, destroying them like bullets hitting bullets. The United States has prevented a catastrophic attack on its homeland and potentially averted a nuclear apocalypse for the entire world.

This is how the Trump administration’s plan for a space-based missile defense, or “Golden Dome,” might work, though it is still just a hypothetical capability. The program is the latest iteration of the decades-long vision to protect America from nuclear or conventional strikes. Whether or not Golden Dome is fully realized, the program may reshape U.S. defense and the global arms race.

“Strong believers in international norms, in the United States leading by example and forbearance, they probably won’t be happy with this” Golden Dome approach, says Peter Garretson, a senior fellow in defense studies at the American Foreign Policy Council.

Whereas, Garretson adds, “anybody who’s actually aware of how easily and unprotected we are against these threats, and I suspect the American people, probably are happy about this.”

President Donald Trump’s “Iron Dome for America” executive order, signed Jan. 27, says that the United States must “provide for the common defense of its citizens and the Nation by deploying and maintaining a next-generation missile defense shield.” It specified that this defense should include “proliferated space-based interceptors capable of boost-phase intercept,” meaning striking the missiles over enemy territory while they are still accelerating. The “Iron Dome” in the title was an unmistakable reference to Israel’s missile defense capabilities for low-tech, short-range rockets — but the Department of Defense has since rebranded this entirely distinct and much more ambitious program with the “Golden” moniker.

The order directs the secretary of defense to produce and deliver a detailed “reference architecture” in 60 days, meaning late March. To get going, the Space Development Agency in early February announced the release of a “special notice” seeking ideas from industry for the architecture. It followed a “request for information” from the Missile Defense Agency seeking “innovative missile defense technologies” and ideas for accelerating an existing missile-tracking-satellite development program.

“We’re going to protect our citizens like never before,” Trump said about the Golden Dome during his joint address to Congress in March.

The proposal hearkens back to President Ronald Reagan’s 1983 Strategic Defense Initiative. That “Star Wars” plan sought to build a space-based missile defense constellation that would protect America from a nuclear attack and so make nukes obsolete. It would shield the U.S. “from nuclear missiles just as a roof protects a family from rain,” as Reagan described it in 1986. The concept soon evolved to include the pursuit of “Brilliant Pebbles,” small spacecraft in low-Earth orbit that could collide with ballistic missiles and intercept them in boost phase. The collapse of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War removed the urgency for developing and paying for this kind of technology, and the U.S. scaled back the program before finally discontinuing it in 1994.

Defending the U.S. against such rogue actors became the cornerstone of its missile defenses. Today, there are 44 ground-based interceptors in Alaska and California that would protect the U.S. against a limited strike. In 2018, Congress authorized funding to develop a space-based missile interceptor layer, and the Trump administration’s 2019 Missile Defense Review argued that space exploitation provides a missile defense posture that is more “effective, resilient and adaptable to known and unanticipated threats.”

Project 2025, the Heritage Foundation’s presidential policy outline, advocates for missile defense in the Pentagon chapters written by Christopher Miller, the former acting secretary of defense in the final months of the first Trump administration. Miller describes missile defense as a “critical component of the U.S. national security architecture” and argues that the country should “accelerate the program to deploy space-based sensors that can detect and track missiles flying on nonballistic trajectories.”

He also advocates changing U.S. missile defense policy, which for some 20 years has focused on deterring attacks from rogue states, to one focused on competitors with the most advanced arms. Trump’s executive order does this, explicitly referring to defending the U.S. against attacks from “peer and near-peer adversaries.” That is, China and Russia. It represents a broad mission shift, says Cameron Tracy, research scholar at the Berkeley Risk and Security Lab.

“Trying to defend against a Russian or a Chinese hypothetical attack is a very different story — both politically and technically — than defending against a hypothetical North Korean attack,” Tracy says.

Unlike a rogue actor that could send one or maybe a few ICBMs toward the United States, China and Russia have substantial arsenals of strategic missiles and could invest in building more.

“Given the increasing reliance on nuclear capabilities and on long-range missiles by our adversaries, we have to change what we’ve been doing,” says Robert Peters, a research fellow in nuclear deterrence and missile defense at the Heritage Foundation.

Russia regularly issues coercive nuclear threats. China is rapidly and vastly expanding its nuclear arsenal; according to independent and defense intelligence assessments, China possesses approximately 600 warheads, with the aim of producing 1,000 nukes by 2030. “We have to open the aperture to include shooting down missile threats from China and Russia, given their behavior over the last 10 years,” Peters adds. “That’s the impetus.”

But some see this policy shift of directly calling out peer adversaries as destabilizing, the start of a costly arms race to the bottom that will still fail to protect the American homeland from attacks — or could put the country at greater risk of a confrontation. A missile defense shield would scramble the calculus of mutually assured destruction, the idea that if one country nukes another, it’s going to get nuked right back, which restrains either from striking first because that would mean game over for everyone.

The second-strike capability — the ability to set off mutual destruction — becomes a less potent nuclear deterrent if another country has robust missile defense that could seriously deter ballistic or hypersonic attacks. China, Russia or any other power will respond. They could, in theory, build their own shields, but the cheapest and fastest approach would be to build a heck of a lot more missiles to overwhelm such defenses, much as a 4-meter border fence can be defeated by a 4.5-meter ladder.

It is traditionally more expensive to design and field defenses than it is to design and field offenses. “That has been the lesson throughout the nuclear age,” says Joe Cirincione, an independent nuclear national security analyst who was previously president of Ploughshares Fund, which is working to prevent the proliferation of nuclear weapons and their use. “Whenever one country tries to build a defense, the adversary just builds more offense.”

Proponents of missile defense say their strategy would impose economic costs that an adversary would struggle to meet. They also argue that while more offensive weapons might overwhelm missile defense, that is more a gamble than a guarantee, and that unpredictability of success serves as a deterrent. Others also argue that missile defense could become a potent bargaining chip in negotiating arms limits, though others disagree, because it creates a power imbalance.

Garretson, of the American Foreign Policy Council, says missile defense speaks to an imperative to try to defend the populace: “You cannot count on an enemy choosing not to attack you.”

These are long-standing policy splits on the idea of missile defense, but they’ve taken on a new urgency with Trump’s order. Today’s civilian megaconstellations and microelectronics have opened up new possibilities for the design of such space-based interceptors. The executive order solidifies these interceptors as a core part of ongoing missile defense efforts, adding a new layer to the existing and soon-to-be modernized warning and tracking constellations.

“Specifically asking for space-based interceptors and options, including nonkinetic options” — widely seen as a reference to laser weapons — “to go after the boost phase, this is a major, major policy shift,” says Garretson.

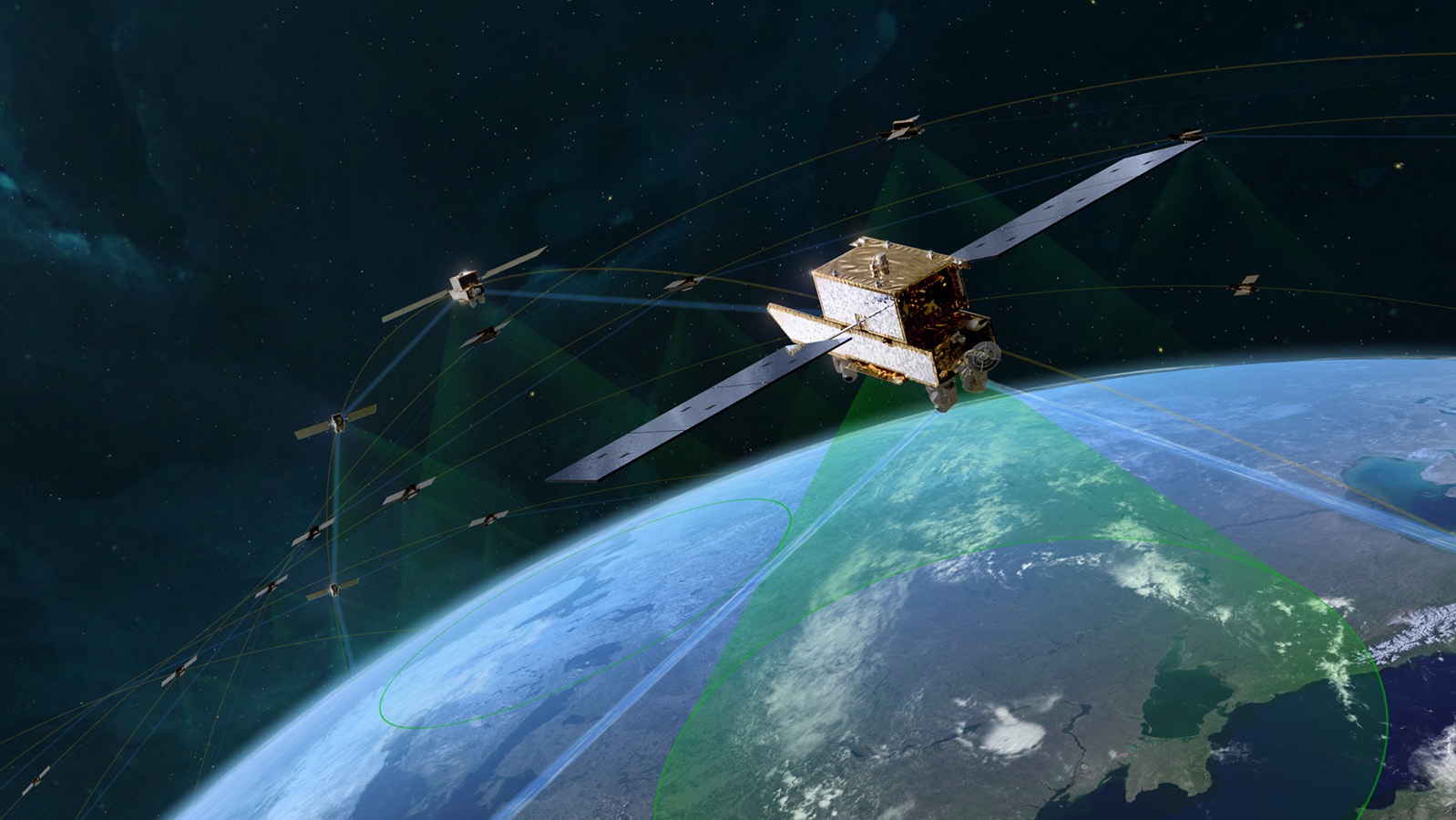

The U.S. would detect missile launches with its existing Space-Based Infrared System satellites in geosynchronous orbit high over the equator. These satellites can tell where a ballistic missile is going and where its warheads are likely to fall, but the United States wants to develop better warning and tracking by creating a Custody Layer — satellites that will watch where all the other guy’s stuff is — and a Tracking Layer that could also determine where more sophisticated weapons, like hypersonic missiles, are headed.

Consider the Hypersonic and Ballistic Tracking Space Sensor satellites, a portion of the Tracking Layer that Trump’s executive order seeks to accelerate. HBTSS provides “the sniper’s high resolution scope, precisely tracking hypersonic missiles in flight,” Northrop Grumman, one of their manufacturers, wrote on its website in 2022.

Together, these components would form the Proliferated Warfighter Space Architecture constellation. Plans call for launching the satellites in “tranches,” or batches, along with a communications or Transport Layer.

“I don’t want to say quite ‘no sparrow may fall,’” — a biblical reference to an all-knowing god — “but it’s pretty close to that,” says Fred Kennedy, a former director of DARPA’s Tactical Technology Office and the founding director of the Space Development Agency.

Precision matters, especially when protecting against threats like hypersonic weapons, which can maneuver and operate in much lower altitudes. And, of course, these satellites need to be able to track potentially dozens or hundreds of missiles headed at a target, or at many different targets, at once. They must also communicate with other U.S. assets and interceptors — on the ground, on warships at sea and, someday, as the “Golden Dome” seeks to do, in space. Exactly how that will all work together in real time is one of the big questions of any sort of advanced missile defense.

The Golden Dome project is proposing an intricate system that is far beyond the anti-missile systems the United States currently has. Some of what the U.S. has is very good, but none of it is perfect. The U.S. has mobile ground-launched defenses, namely the Patriot batteries that have been fired with great success in Ukraine, and the Terminal High Altitude Area Defense, or THAAD, batteries that are deployed in various locations around the world. A THAAD delivered to the United Arab Emirates achieved its first successful combat intercept in January 2022 against a mid-range ballistic missile launched by the militant group the Houthis.

As for the homeland, U.S. defense is limited to those 44 ground-based interceptors in Alaska and California, which, again, were constructed to intercept rogue missiles from somewhere like North Korea. The U.S. keeps a lot of details of these tests under wraps for obvious security reasons, but the public record shows 12 successful intercepts out of 21 tests. But again, these are tests, not real-world scenarios, and the U.S. government is the one designing the conditions. A 2022 study from the American Physical Society found that after 70 years and expenditure of $350 billion, no “system thus far developed has been shown to be effective against realistic ICBM threats.”

Such vulnerability is exactly why proponents believe it’s time to go all in now and make a push for testing and technological development. As Peters says, technology has been improved since the SDI vision 40 years ago, specifically the U.S.’s ability to identify inbound threats. Also, space launch has vastly improved, with Elon Musk’s SpaceX leading the way and competitors United Launch Alliance and Blue Origin now also making progress.

“Forty years ago, the only way to put something in orbit was to go through the government, and now we’ve got multiple independent companies that are able to put kilograms in orbit for not very much money,” Peters says.

Not very much money is relative, of course. The executive order did not include cost estimates. The Defense Department is currently redirecting about $50 billion in funding to what it considers priorities, including this Golden Dome. U.S. Sens. Dan Sullivan (R-Alaska) and Kevin Cramer (R-N.D.) in February introduced the IRON DOME Act, which would put $19.5 billion toward missile defense.

Peters says this might be sufficient to get the program going, but it is unlikely to come anywhere near the actual costs needed to achieve a program of this scale. Todd Harrison, a fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, estimated in a January report that it would cost between $11 billion and $27 billion to launch an initial constellation of 1,900 space-based interceptors. “If this seems like a no-brainer to protect the United States from ballistic missile attack, there’s a catch,” Harrison writes. “The system described above is only sized to intercept a maximum of two missiles launched in a salvo.”

America would be shelling out quite a lot of money, but it likely wouldn’t be sufficient to defend against those peer adversaries, in this view. A more than decade-old study from the National Academies put the cost for an “austere and limited-capability” space-based interceptor system at $300 billion. A 2024 study published in the journal Defence and Peace Economics found that if an attacker were to send between 500 and 6,000 warheads toward the U.S. mainland, the best-case scenario for the U.S., if it had an effective two-layer ballistic missile defense, would be to intercept 90 of them. This would come at a cost of between $60 billion and $500 billion, and eight times more than the attacker would need to spend to stage the attack, according to the analysis. If defenses were half as effective — that is, only 50% of long-range missiles could be stopped — the U.S. would need to spend 70 times more than its potential adversary: $430 billion to $5.3 trillion for between 6,700 and 88,300 interceptors. That is more than the Pentagon’s entire current budget of $850 billion, and with every warhead still having a 50-50 chance of reaching the U.S. mainland.

Anything in space, says Tracy of the Berkeley Lab, is just not a good value proposition. It is expensive and difficult to maintain and defend. For example, if the U.S. wants to defend against a Chinese ICBM, the ideal would be a satellite sitting over Beijing’s launch sites. But that would require a defense in geostationary orbit, putting the interceptor far from Earth, meaning it would need to travel tens of thousands of kilometers to knock out a missile in the boost phase.

Solving the distance problem requires the interceptors to be in lower orbits, but that means they’re moving relative to the terrain.

“If you want to maintain pretty consistent coverage of a certain location, say, Chinese ICBM fields, you then need a lot more satellites, so a lot more interceptors, because each one will only be covering that area for a fraction of the time,” Tracy says. Even if there are a lot of satellites, and a lot of interceptors, they are vulnerable targets for an adversary, and this could accelerate the militarization of space.

Some analysts and supporters of missile defense say space is already militarizing, and the United States is behind in this race. A space-based defense also would give the U.S. the ability to better protect itself and its allies, and, at least technically, it could also defend most anyone from a nuclear attack. Yet others see this effort as a cautionary tale. The Pentagon’s cost overruns and development struggles — on ships and fighter jets — are well-documented. Now, the U.S. is talking about a space-based defense that requires untested and unprecedented coordination.

“The idea of an impenetrable missile shield over the United States is not achievable,” says Laura Grego, senior research director for the Global Security Program of the Union of Concerned Scientists. “It’s ruinously expensive and strategically unwise, because what you’ll do is your adversary will just build more and it will always be much less expensive for them to spend a little bit more to make you spend a lot.”

Grego suggests the United States could very likely outspend North Korea. But even then, there are no guarantees that doing so will protect America, and its allies, like a roof against rain. “We have not demonstrated yet that we can defend reliably, that the system we have has been demonstrated to work reliably.”

About jen kirby

Jen is a freelance journalist covering foreign policy, national security, politics, human rights and democracy. Based in New York, she was previously a senior reporter at Vox.

Related Posts

Stay Up to Date

Submit your email address to receive the latest industry and Aerospace America news.