Stay Up to Date

Submit your email address to receive the latest industry and Aerospace America news.

Funds and pledges of funding have been pouring in from large corporations to a handful of small companies that are pioneering a proposed new mode of transportation for average people. Does the investment trend guarantee that this class of electric-powered rotorcraft will soon take off with us aboard? Aaron Karp spoke to the industry executives who should know.

It is a seductive vision of the future of short-haul transport: Perhaps as soon as 2024, people will be able to commute to work or head to the airport via electric-powered air taxis flying over the congestion of large metropolitan areas. By the 2030s, these aircraft would be ubiquitous (and, in many cases, remotely piloted), giving a wide swath of the population access to the most modern of transportation services.

But is this vision realistic? A broad spectrum of corporations seem to have answered “yes” by pledging billions of dollars for development over the past two years and making commitments to buy or lease thousands of this proposed new breed of aircraft. A closer look shows an industry whose executives often readily acknowledge that they are taking a gamble, with not everyone convinced it will prove to be a worthy one.

$10 billion investment

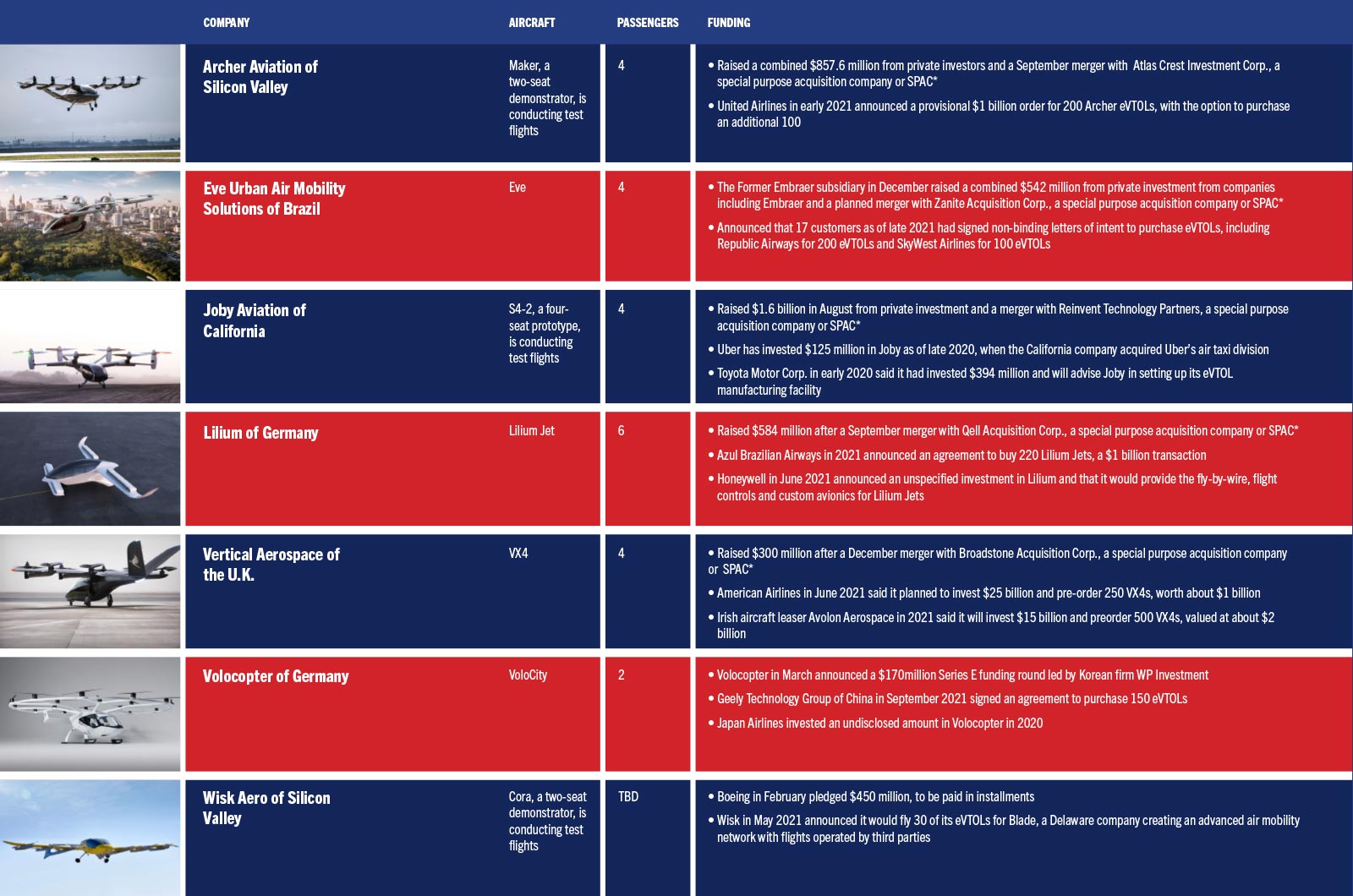

Most plans call for electric vertical takeoff and landing, or eVTOL, designs, and in fact the figurative order book for eVTOLs stretches to at least 3,600 units, according to AirInsight Group, a consultancy with offices in Detroit and Washington, D.C., that tracks eVTOL commitments. For now, these are all provisional orders from a who’s who of corporations around the globe, and acting on those orders depends on manufacturers earning certifications from FAA, the European Union Aviation Safety Agency and Japan’s Civil Aviation Bureau.

Investors include major airlines, the world’s three largest commercial aircraft manufacturers, automobile companies, ride-share corporations and technology firms. They are selling their stockholders on the idea that this nascent technology is aviation’s next evolutionary step. At first, flights are expected to be in the 40- to 80-kilometer range and expand to around 160 km as engineers and scientists improve the technology.

In 2021 alone, investment pledges in the eVTOL sector topped $5 billion, as much as the previous five years combined, according to the Vertical Flight Society, a Fairfax, Virginia-based technical organization.

Among them, American Airlines last year acquired 11,250,000 shares of eVTOL developer Vertical Aerospace of Bristol in the U.K., making the airline a holder of 5.4% of Vertical’s equity, according to a U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission filing. American’s $25 million investment in Vertical was done through a private investment in public equity transaction, or PIPE, which means the airline acquired the shares directly from Vertical instead of via the stock market. American also placed a provisional order for 250 of Vertical’s VX4 eVTOL aircraft, a four-passenger-plus-pilot design whose first flight could come this year.

Mathew Sebastian, American Airlines’ managing director of corporate development and planning, says American “100% believes” in the potential of eVTOLs, adding that the world’s largest airline is just one of a number that have ordered air taxi rotorcraft.

My review of public announcements shows that globally, 10 passenger airlines have placed provisional orders or committed to leasing agreements for eVTOLs.

For instance, in addition to American, Vertical’s roster of equity holders includes Virgin Atlantic Airways.

“Airlines believe that our model is realistic,” Eduardo Dominguez Puerta, Vertical’s chief commercial officer, told me in an interview.

Perhaps Vertical’s most important investor is Irish commercial aircraft leasing giant Avolon Aerospace, which has not only placed a provisional order for 500 VX4s but has also announced leasing deals with airlines for 450 of those 500 aircraft. As part of Avolon’s 2021 agreement to become an equity holder in Vertical, it provided $15 million to Vertical, and Avolon CEO Dómhnal Slattery is now the chairman of Vertical’s board of directors.

“The eVTOL market has definitely benefited from the inflow of capital,” says Marc Tembleque Vilalta, a vice president for airline analysis at Avolon-e, the company’s unit managing eVTOLs. “Why now? We believe this is going to be a supply-constrained market for some time, so timing is critical.”

At the Singapore Airshow in February, Avolon made a splash by announcing a provisional leasing agreement with AirAsia for 100 of its 500 VX4 aircraft. The Malaysia-based low-cost airline has one of southeast Asia’s most extensive passenger networks.

Target markets

Companies developing eVTOLs for what has come to be known as advanced air mobility or urban air mobility see three primary potential use cases:

Shuttling airline passengers to and from airports and between airports in cities that have multiple airports, such as New York and London.

Carrying commuters to their offices. For these customers, Joby Aviation of California plans to take advantage of structures that suburban residents know well. “Parking garages have a lot of the characteristics you need — places for customers to park with big flat tops,” says Eric Allison, Joby’s head of product. Joby has a partnership agreement with REEF Technology and Neighborhood Property Group, a Miami-based parking lot owner and operator, to jointly develop rooftop “skyports.” Commuters would park at these suburban garages and then go to the roof to catch eVTOL flights to the city center.

Linking nearby cities with each other or linking islands in places like Hawaii. Developers generally concede this eVTOL application will likely be added once the first two uses are established.

Airlines say that their greatest interest, at least initially, is to give passengers a means to get to airports faster.

“For example, you could connect San Francisco International Airport with suburbs that now require a very long drive,” says Michael Whitaker, the chief commercial officer of Supernal, the eVTOL arm of South Korea’s Hyundai Motor Co.

Supernal, which was launched in November 2021, aims to have its eVTOL enter commercial service in 2028. As an automaker, Hyundai will be able to develop an automobile-style assembly line manufacturing process for eVTOLs, adds Whitaker.

The world’s biggest aircraft manufacturers have also thrown their monetary support behind the eVTOL industry, believing their experience certifying and bringing new airplanes into service will provide an advantage over automobile manufacturers and other developers.

Boeing has pledged $450 million in a series of installments to Silicon Valley eVTOL developer Wisk Aero, which aims to begin passenger flights with its remotely piloted eVTOL design by the end of this decade. Boeing plans to partner with Wisk in all aspects of development. Airbus is experimenting with its own prospective eVTOL design called CityAirbus NextGen. And Brazil’s Embraer, the third largest commercial aircraft manufacturer in the world, has established Eve, a subsidiary charged with developing an eVTOL.

Keeping perspective

“There’s a lot of momentum around eVTOLs,” Airbus Group CEO Guillaume Faury said during a February virtual press conference to discuss the company’s annual earnings. “I can only welcome this appetite for eVTOLs.”

However, he cautioned against excessive exuberance. “A lot needs to happen before we have a market that starts to create revenues and margins,” Faury said. “There’s still development needed on the technology, on the certification process, on the regulations for operations. We’re investing at Airbus. We see many others investing.”

He added: “But I believe there still is work to be done before we come to real commercial operations.”

Indeed, skeptics point out that the only way for the fledgling sector to generate a sizable profit would be to manufacture aircraft at a massive scale that will be difficult to achieve — at least for the foreseeable future. While eVTOL developers and investors tout the anticipated low per-trip operating cost of the battery-powered rotorcraft, Richard Aboulafia, the managing director of Washington, D.C.-based AeroDynamic Advisory, has said the per-aircraft production cost is expected to be in the $4 million to $5 million range, at least initially.

“I don’t often get exclusive use of a $5 million machine,” he tells me, noting that eVTOL operators are developing aircraft to carry just one to four passengers per trip. “Everyone is so focused on operating costs that they forget about capital costs.”

Aboulafia believes anything other than a limited market for high-end passengers in select cities such as São Paulo, Brazil, is unrealistic this decade. He is critical of Boeing’s investment in Wisk, saying it is far afield from the manufacturer’s core aircraft manufacturing business, which has been plagued with high-profile technology and manufacturing issues in recent years on its 737 MAX and 787 Dreamliner programs.

“How does it impact their core business at all?” Aboulafia wonders aloud. “About 1% of Boeing’s business, at the most, relates to flights of less than 500 miles, let alone 25-50 miles. What’s the relevance here?”

Aboulafia cautions that eVTOL investment and order announcements should be taken with a grain of salt, noting most of the money is pledged rather than paid and the orders are all provisional.

eVTOL developers, while generally confident in the technology, do acknowledge serious challenges ahead. Whitaker of Supernal notes that an entire operational infrastructure also needs to be established. Vertiports have to be built and be plentiful enough that consumers do not have to drive too far to reach a takeoff spot, which would of course defeat the purpose of flying. Also needed are numerous eVTOL charging stations.

“If you’re manufacturing cars, you don’t have to worry about roads and gas stations,” he says. “We don’t have any of that.”

Pressed by a reporter at the February earnings press conference about the wisdom of Airbus investing in “speculative” technology, Faury said that even if commercial eVTOL services do not come to fruition until the distant future, research on electric batteries would be applicable to the next-generation airplanes coming to market in the 2030s.

“It makes a lot of sense for us to be part of the eVTOL ecosystem,” he said.

Boeing has similarly said its investment in eVTOLs is part of a wider sustainability strategy. “We are always looking for ways to reduce our environmental impact,” Heidi Hauf, Boeing’s Asia-Pacific sustainability lead, tells me.

Executives, particularly those at eVTOL companies, remain confident about the commercial viability of the technology. One of them is Vilalta, the Avolon-e vice president.

“The value proposition for passengers is very high when you look at the time they will be saving,” he says. “And eVTOLs will be much simpler to maintain” than conventional aircraft, “which takes a lot of the cost out right there.”

However, he says eVTOLs entering service this decade will be mostly limited to high-end passengers able to pay a premium. “There’s going to be a phase initially where OEMs are not going to be able to produce at scale, and demand will outstrip supply.”

That means the faster developers can get aircraft to market, the faster they can move through the costly proving period.

“We’re not doing this to develop a premium service only for high-end passengers,” Wisk CEO Gary Gysin says.

Joby, which early this year had two prototype aircraft in flight testing, believes it can achieve certification in time to begin passenger flights in 2024 with its four-passenger piloted aircraft. It has already started the FAA certification process. The company had a setback on Feb. 16 when one of its prototype eVTOLs — the same model Joby plans to bring to service, but in this case flown remotely without an onboard pilot — crashed during flight testing in California. There were no injuries, but a preliminary report from the U.S. National Transportation Safety Board said the aircraft was “substantially damaged.”

Allison says Joby expects to “rapidly scale” production and operations once its aircraft enters commercial service. Joby plans to be the OEM and operator of the vast majority of its eVTOL aircraft. Toyota Motor Corp. is Joby’s leading equity holder, investing $394 million in the company.

Also, Joby, Toyota and Tokyo-based All Nippon Airways entered into a partnership in February to develop an eVTOL market in Japan, with an important distinction.

“ANA is not investing any money in Joby, and the relationship with Joby is simply a partnership to begin studying the potential of air mobility in the Japanese market,” Yuki Horie, the project director of ANA’s Digital Design Lab that explores future transportation technology, tells me by email. “We are targeting the introduction of eVTOL aircraft in Japan by around 2025, but whether this will be for commercial use is yet to be decided.”

Advanced air mobility firms are counting on the public to grasp the potential of eVTOLs and warm to the technology. “From our perspective, it’s almost like being in the 1980s with the advent of the desktop computer,” Superal’s Whitaker says. “I think it’s that kind of innovation. It will be a metro rail system in the air.”

How has all this investment changed the sector? In the view of Vertical’s Puerta, the investments contributed to whittling down a field of dozens of prospective players to half a dozen or so with the financial backing to have credible hopes of succeeding.

“Investors have made their bets,” he says.

“A lot needs to happen before we have a market that starts to generate revenues and margins. There’s still development needed on the technology, on the certification process, on the regulations for operations.”

Guillaume Faury, Airbus Group

About Aaron Karp

Aaron is a contributing editor to the Aviation Week Network and has covered the aviation business for 20 years. He was previously managing editor of Air Cargo World and editor-in-chief of Aviation Daily.

Related Posts

Stay Up to Date

Submit your email address to receive the latest industry and Aerospace America news.