Ending the frantic searches

By Keith Button|September 2019

Cockpit voice and data recorders almost always survive crashes, but finding them can take years if they are ever recovered. Two concepts could potentially solve that problem, but regulators have yet to embrace either of them. Keith Button looks at the technical and regulatory questions swirling around this issue.

Authorities spent 1,046 days searching for the black boxes and wreckage of Malaysia Airlines Flight 370 in the Indian Ocean. At one point, tantalizing news broke that an Australian ship may have detected pings from an underwater beacon on either the cockpit voice recorder or the flight data recorder. The trouble was, the pings were faint, suggesting that the locator batteries were running low or that the searchers were still far away. At this writing, neither the flight data nor cockpit voice recorder has been found.

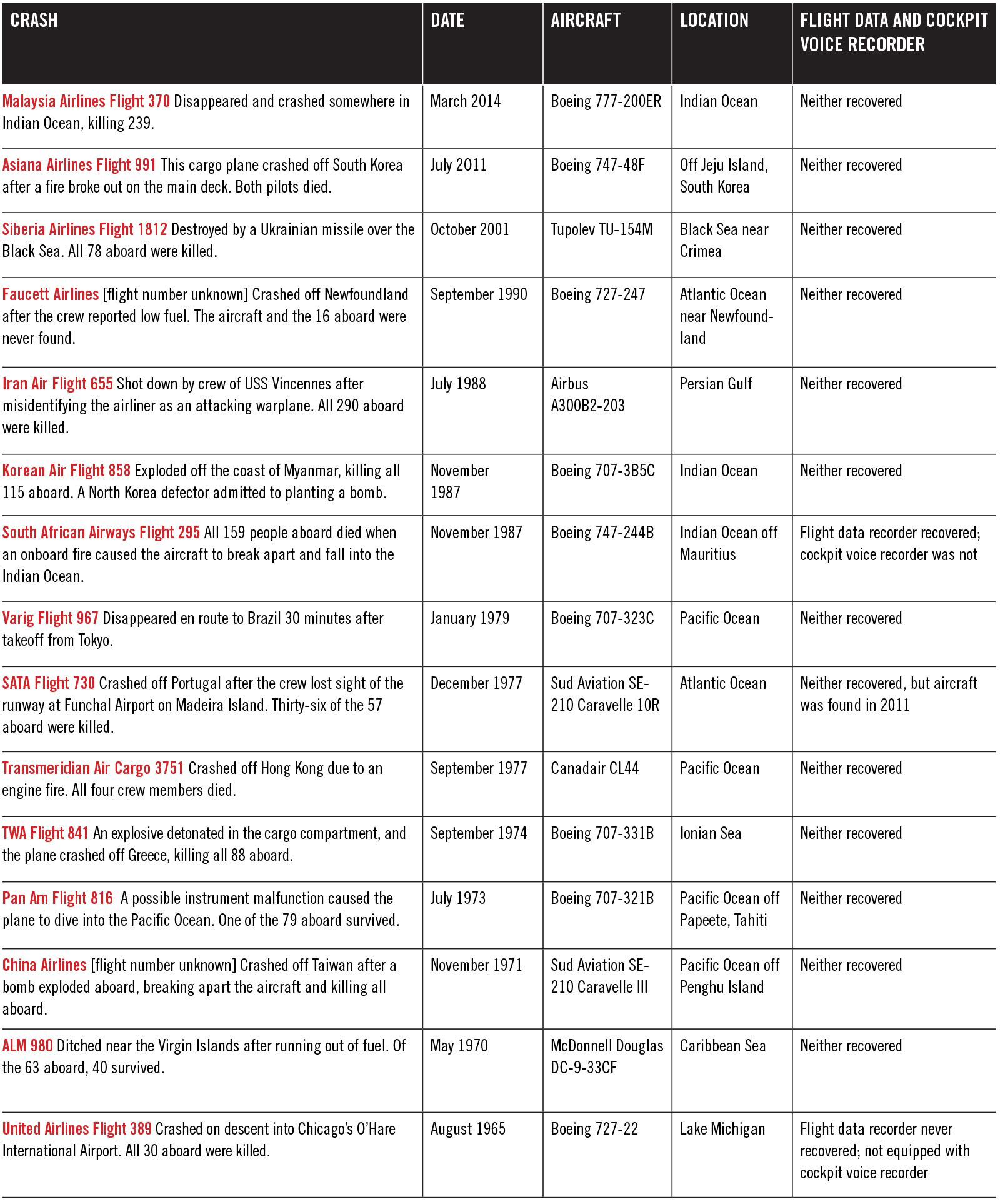

In this respect, MH370 is not unique. Records show numerous cases in which one or both of the recorders was never recovered.

On Jan. 1, 2021, the air transport industry will take what could turn out to be a momentous step toward ending these desperate and sometimes fruitless searches for black boxes. That’s when a technical standard goes into effect calling for “timely recovery” of flight data and cockpit audio. The standard was approved in 2016 by the United Nations International Civil Aviation Organization, ICAO. Though the standard is not a requirement and it is aimed at freshly minted designs, some in the industry hope airlines will agree to it and retrofit their existing aircraft too. This would prevent some planes flying out of scope with such an important safety standard.

Whether the standard will have the desired impact remains unclear. A fierce competition is playing out between two basic concepts: ejectable black boxes versus technology for streaming cockpit voice and flight data to the ground via satellite. Meanwhile, another camp argues that the aircraft tracking requirements established after MH370 suffice.

Airbus favors the ejectable boxes, also known as automatic deployable flight recorders, and, in fact, has begun installing them on its newest jets. As for Boeing, the company says deployable boxes need more study partly due to the “risk of inadvertent deployment over populated areas.” Boeing tested streaming technology on its 777 EcoDemonstrator in 2018 and says that this technology, too, has “unresolved technical and safety issues that must be addressed.”

Missing regulations

The ICAO standard applies to new designs carrying at least 19 passengers and weighing 27,000 kilograms or more. If newly certified Airbus and Boeing passenger jets are about the size of today’s, all will be covered by that weight threshold. Often a standard like this one would be reflected in regulations crafted subsequently by the European Union Aviation Safety Agency, which certifies new Airbus designs, and the FAA, which certifies new Boeing designs. Those aircraft comprise 99% of the large passenger jet market, according to Teal Group of Virginia. FAA told me in a statement that it “does not plan to implement regulations on this issue,” because it feels that existing regulations already meet or exceed the ICAO timely recovery standard. EASA says “quick retrieval” of flight recorders will be assured by a 2023 mandate requiring aircraft to be equipped with a “robust and automatic means” of determining the “end point” of a flight so that the precise crash location can be deduced.

Ultimately, it could be regulators from the Asia-Pacific region who take the lead on turning the standard into a requirement, given the oceanic nature of their routes and their frustrations over the MH370 disappearance, says Miguel Marin, ICAO’s head of operations. He predicts that regulators there will require aircraft in their airspace to have new technologies onboard that meet the ICAO standard.

Of course, even if regulators do turn the standard into a requirement for new designs, that could still leave thousands of existing aircraft flying for years to come with the older technology. I contacted a sampling of U.S. airlines to find out if they plan to retrofit their fleets to meet the timely recovery standard. Delta Air Lines said, “We feel that we have the ability with current tools to meet the expectation” of the ICAO standard “without having to purchase new or unplanned technology.” Southwest Airlines said it “does not have a position on the topic.” United Airlines deferred to the Airlines for America, a lobbying group, which said, “there are already near real-time streaming flight data capabilities on newer aircraft and a growing percentage of the overall U.S. airline fleet.” This is a reference to the maintenance data that airlines are starting to receive from aircraft in flight via services offered by the manufacturers. The group also noted that the Automatic Dependence Surveillance-Broadcast, or ADS-B, radios that airliners are starting to carry “provide the accuracy and safety benefits of real-time surveillance,” the implication being that the location data in the ADS-B transmissions would narrow the search area and assure timely recovery.

Not everyone agrees, including the chair of the ICAO group that wrote the guidance for the timely recovery standard. “There are a lot of people thinking that because you find the wreckage under water, you will find the recorder automatically, 100%,” says Philippe Plantin De Hugues, a senior safety investigator at BEA, the French aviation accident investigation agency. He has documented at least 15 over-water accidents in which either the cockpit voice recorder, the flight data recorder or both were never found. He noted that searchers needed two months to find the cockpit voice recorder for the Lion Air 737 MAX that crashed last October off Indonesia in only 30 meters of water. As for the maintenance data, he says it’s insufficient for accident investigators.

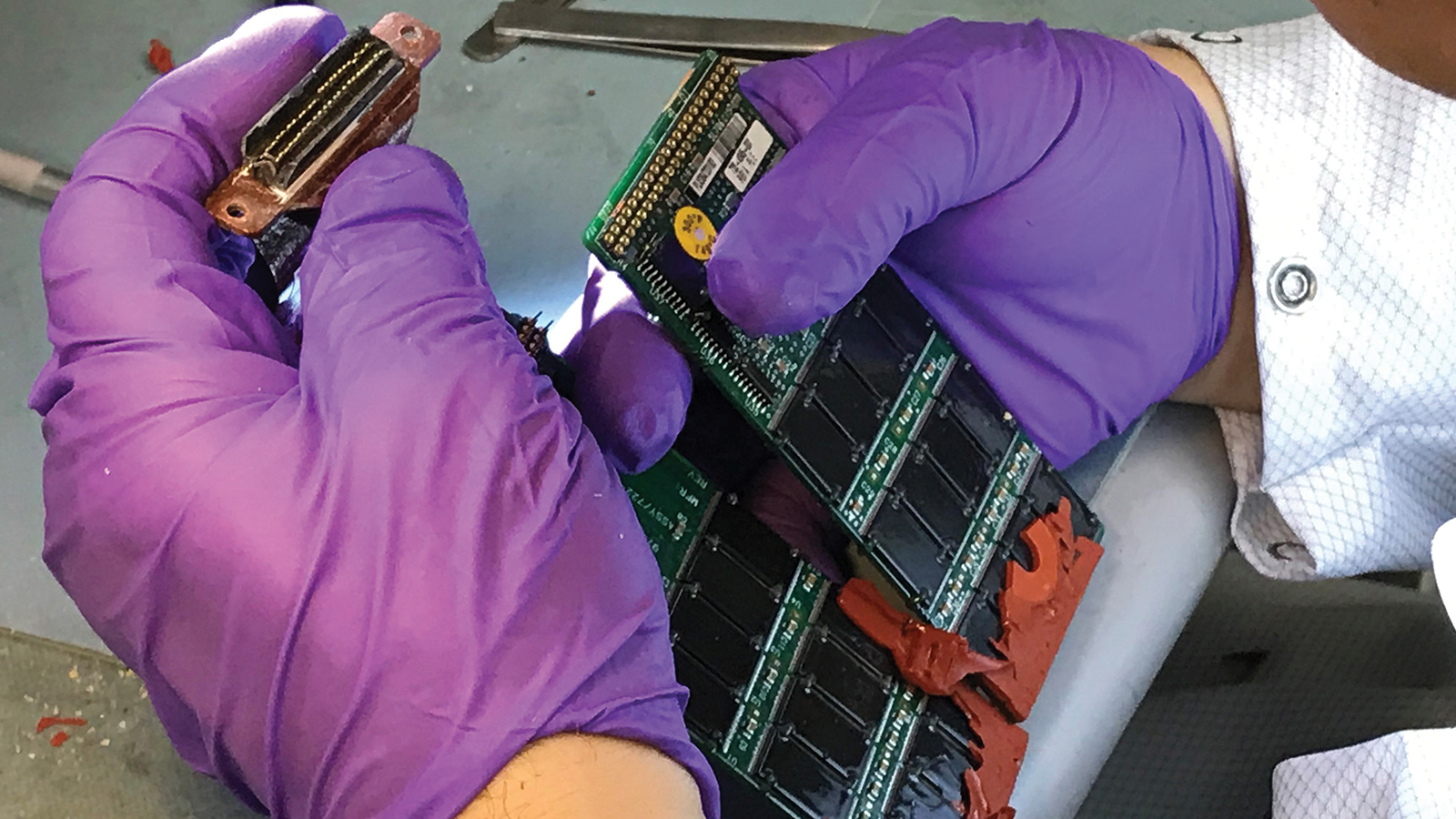

Ejectable boxes

Avionics supplier L3Harris Technologies of Florida says the standard can be met by the combined cockpit voice and flight data recorder that it has begun selling. This Automatic Deployable Flight Recorder would spring from the tail of the plane on impact and, in a water crash, float instead of sinking with the wreckage or debris like conventional black boxes. The device is recessed into the surface of the fuselage to avoid aerodynamic complications. Conventional black boxes are sometimes carried in the tail as separate boxes for audio and data, while other versions combine the functions into one box, and then for redundancy identical versions are kept on an equipment rack in the front of the plane and in the tail.

Airbus has endorsed the ejectable concept, and the company is installing one on each A350 XWB, the new wide bodies that Airbus started delivering this year. The company pledges to install the boxes on all future Airbus planes too.

Streaming data

Another school of thought calls for avoiding the need to recover black boxes at all. The data would be streamed, and to keep satellite communications costs under control, this probably would be done by triggering the service in an emergency.

Curtiss-Wright Corp. of North Carolina and erstwhile rival Honeywell of New Jersey are jointly developing black boxes that would do this. Meanwhile, FLYHT Aerospace Solutions of Calgary, Alberta, which worked with Boeing on the streaming demonstration in 2018, is marketing a black box streaming service but has so far lined up only a handful of customers, including First Air, an Ontario-based airline, the only one that it named. These customers have signed up for flight data streaming, not voice. The cost of satellite bandwidth is a big challenge for these concepts.

In fact, Plantin De Hugues offers a tentative prediction. He says until the transmission prices come down, the near-term solution may be the ejectable black boxes. He offers a caveat: Installations of ejectable boxes can be expensive, which could make short bursts of data an attractive alternative.

Backers of streaming are upbeat about carving a near-term role.

FLYHT addresses the cost problem by giving its customers the option of triggering its black box service, called FLYHTStream, only in an emergency, says Derek Graham, FLYHT’s chief technology officer.

Thomas Schmutz, the FLYHT CEO, predicts that satellite bandwidth eventually will become a commodity and, as with cellphone data plans, prices will come down. With lower prices, aircraft in the future will be connected via satellite links to the ground continuously, Schmutz says, and aircraft operators will be able to view all the aircraft data in real time, on the ground. Eventually, customers could view virtual projections of aircraft in flight that would allow on-the-ground safety monitoring and diagnosis of technical problems before they lead to crashes.

Streaming costs would add up quickly today if it were done continuously, given the potential volume of data produced by each airplane. Today’s passenger plane flight data recorders record at least 88 flight data parameters — the minimum required by the FAA — such as the position of control surfaces on the wings and engine data, for example. Data recorders for newer passenger planes like the Airbus A350 and Boeing 787 can record thousands of parameters, so the bandwidth required to transmit all the data, and the associated costs, could be substantial.

Hardware costs might or might not prove to be a big obstacle. Rigging an airliner for streaming would cost $70,000 per plane, according to the 2015 “Air Safety” report by the U.S. Government Accountability Office. That’s about 0.03% of the cost of a Boeing 787 or Airbus A350 XWB. Of course, even a small increase adds up to a large number across thousands of aircraft.

Difficult choice

Another question is what satellite frequency to communicate in. Because of their wavelength, L-band satellites can establish links with aircraft even through clouds and precipitation. The L band already carries airplane tracking data via Iridium satellites and the Aireon aircraft surveillance service, for example. But there isn’t enough L-band spectrum available to handle the volume of data that black box streaming would demand, says Lisa Kuo, director of connectivity technical sales at Panasonic Avionics Corp. of California, which supplies passenger communication and entertainment services to airlines.

The higher-frequency Ku- and Ka-band options, which carry internet and streaming services for airplane passengers, are less reliable in wet weather. That said, Ku and Ka bands may be a more likely option for black box data streaming because the cost to transmit data via L-band satellites is more than 10 times that of Ku and Ka bands, Kuo says.

In fact, this might be one reason that some expect authorities to always want black boxes in some form on a plane, even if it is equipped for streaming. Today, each box weighs about 3 kilograms, so keeping them does not pose an equipment challenge. Regulatory authorities will always want recorders aboard in case the satellite link fails or another unforeseen problem arises, says Chris Thomson, the United Kingdom-based vice president for business development at Curtiss-Wright.

Securing the audio and data stream

Those who favor streaming know that the transmissions must be encrypted to protect them from hackers. ICAO has urged regulators to make sure that satellite-streamed data is not intercepted or altered as it moves from the plane to the ground.

Honeywell and Curtiss-Wright are still ironing out the level of encryption that will be necessary for the downlinks from their data-streaming flight data and cockpit voice recorders, says Curtiss-Wright’s Thomson. Whether the data encryption should be equivalent to that of military communications in a war scenario, or to that of an online credit-card purchase, or some other level, has yet to be decided. At issue is making sure the data is secure while balancing the costs and benefits for the chosen level of encryption.

Those who watch developments in this area see promise in the concept. If the plane crashed, “now you have the flexibility of having real-time data,” says Daniel Adjekum, an assistant aviation professor at the University of North Dakota and former aviation accident investigator in Ghana. Investigators could quickly decide which aircraft components or flight crew actions to focus on.

They could see from the streamed data where the aircraft departed from its assigned altitude and its rate of descent, for example, along with essential information that might be gleaned from the pilot’s control inputs and communications, or from engine data.

Combining with other standards

In addition to timely recovery of flight data, ICAO issued two other standards in 2016 aimed at preventing another lost plane scenario like MH370. One standard requires planes to transmit their location at least every 15 minutes; the other requires planes in distress to transmit their location once a minute via a system that cannot be shut off by someone on the plane. The 15-minute standard is met by the ADS-B radios that most airliners carry and will have to carry in the U.S. starting in January. ADS-B does not fully meet the once-a-minute standard, because the ADS-B transponder could be shut off by someone.

Despite their limits, ADS-B transmissions figured into Canada’s fast response to the crash of the Ethiopian Airlines 737 MAX jet in March after takeoff from Addis Ababa. The transmissions were picked up by Iridium satellites and routed to NAVCANADA, the Canadian air traffic control company that is part of the Aireon surveillance venture. Canadian authorities realized that the flight path resembled that of the Lion Air 737 MAX that crashed a few months earlier, and so they grounded all MAX planes in their airspace as a precautionary measure.

With streaming, investigators would have far more data to go on right away plus the cockpit conversation. “We can certainly imagine a world where [the Boeing 737 MAX crash data] would have been more available much more quickly for whatever the corrective action might have been, to have started earlier rather than later,” Thomson says. “The more quickly and the more data you can pull off the aircraft, the better chance you have of converting that data into timely information upon which you can take some sort of investigative or corrective action.”

Implications for maintenance, repair and overhaul (MRO)

The 2021 deadlines are spurring demand by airlines not just for streaming black box data, but data that could improve their flight operations. For example, FLYHT, the streaming company, offers thousands of parameters for airplanes in flight for real-time monitoring of fuel consumption, crew performance, weather conditions and airplane health. Customers — the airplane operators — can make in-flight adjustments based on the data to save on fuel costs or diagnose maintenance problems in flight before they lead to costly repair problems, or spot airplane health problems that could interfere with on-time performance goals. If they are already setting up a satellite link for transmitting the black box data, then it might make business sense to carry maintenance and operations data over the link also, or vice versa.

As new technologies are wrapped into aircraft, one thing innovators plan to stay focused on is their culture of safety.

“Aerospace is a very conservative industry, with a lot of room for innovation, but that innovation is always tempered,” Thomson says. “We operate in three dimensions. You get into a bit of difficulty in your car, and you pull over. You can’t really pull over at 38,000 feet, so there’s always a preponderance of safety.”

Related Topics

Commercial Aircraft