Stay Up to Date

Submit your email address to receive the latest industry and Aerospace America news.

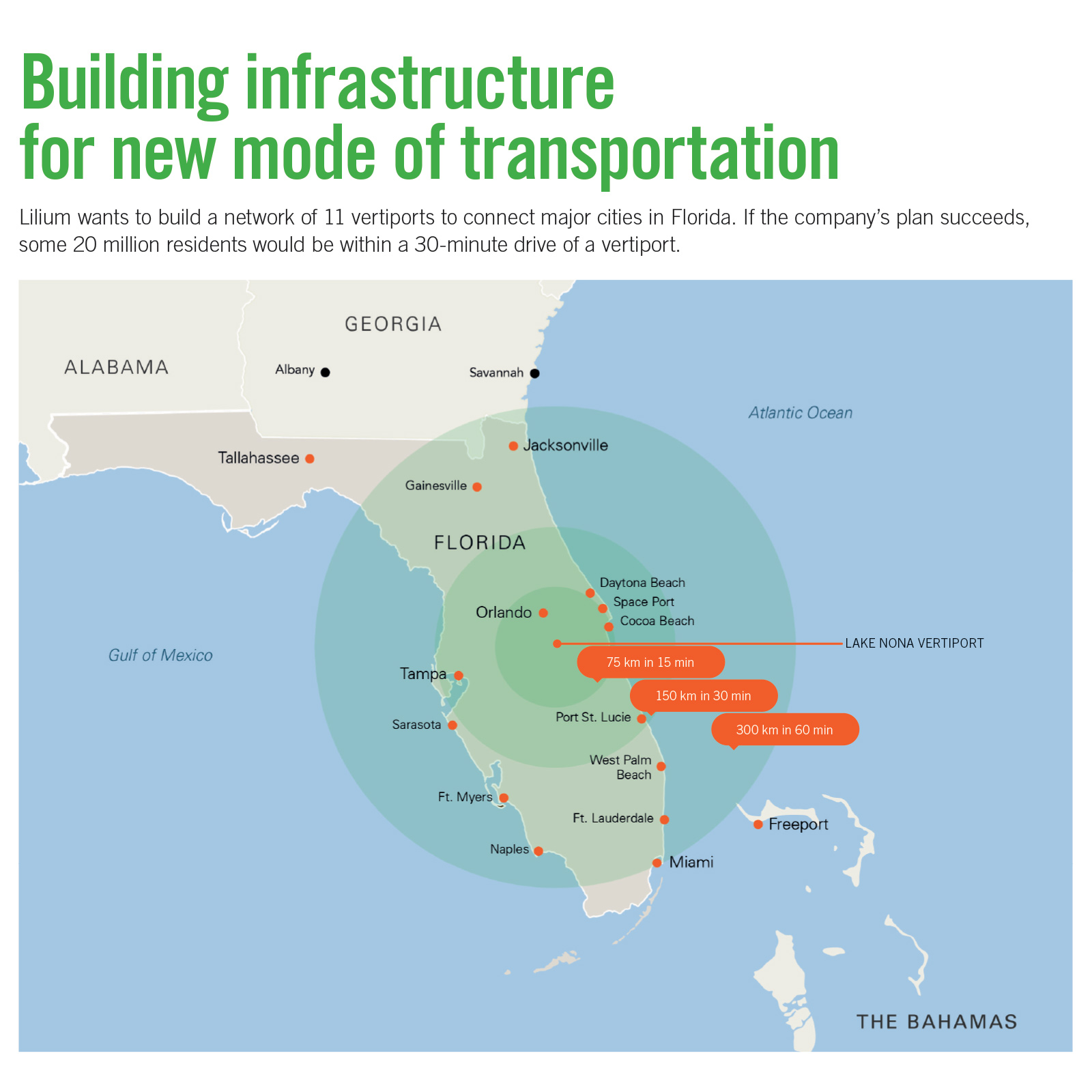

Metropolitan areas including Miami and Orlando have emerged as potential early adopters of urban air mobility flights aboard electric aircraft. But this new mode of travel won’t take off unless UAM companies make the right business decisions about where to locate their vertiports and win permission from local authorities to build these landing pads. Cat Hofacker and Alyssa Tomlinson explore the distinct approaches unfolding in Florida.

In Lake Nona, Florida, a planned community south of Orlando International Airport, autonomous Beep buses (with human attendants aboard) carry passengers here and there, poles with Verizon 5G cellular equipment are being installed to test autonomous mobility, and the windows of office buildings automatically adjust their transmissivity based on cloud cover and time of day.

These innovations are among the reasons the community has dubbed itself a “living lab.” The newest reason remains, at the moment, an undeveloped expanse of pinelands and grasses that starts across the street from the University of Central Florida College of Medicine. Somewhere among these parcels Tavistock Development Co., the U.S. real-estate arm of the United Kingdom-based Tavistock Group investment company, plans to erect a vertiport, a single-story building with two landing and takeoff pads out back, technically called FATOs, short for final approach and takeoff areas. As early as 2024, electrically powered aircraft would whisk tourists or residents in minutes between these pads and other Florida cities, such as Tampa, 140 kilometers away, or West Palm Beach, 250 kilometers away.

If all goes as planned, this vertiport would be the hub of a regional and urban air mobility network, and one that will vie against other networks to serve as a springboard to an entirely new mode of transportation in the United States. Residents would have vastly more options about where to live, and for some, the calculus about how far is too far to go for dinner would be forever changed.

Success, analysts and researchers caution, must be defined as capturing a large number of passengers, not just the ultra-wealthy. That hinges on pricing and also how well these companies locate and design their vertiport networks.

“It’s important to recognize the opportunity for UAM to connect areas that could benefit from revitalization — especially where other modes of transportation would allow for seamless intermodal connections,” says Laurie Garrow, co-director of Georgia Tech’s Center for Urban and Regional Air Mobility.

Location, location, location

First and foremost among the challenges is that, in contrast to Lake Nona’s newness and zest for innovation, most other vertiports planned in Florida and around the globe will have to be built around existing and, in many cases, aging infrastructure.

Here’s how Duncan Walker, CEO of the U.K.-based infrastructure company Skyports, sums up the challenges: His picture-perfect vertiport site would be a flat, open field that’s entirely protected from wind and harsh weather events. It would also sit at the heart of a densely populated urban center, where rail and bus transit systems converge and it’s easy to deconflict with other air traffic. In other words, it doesn’t exist.

“There’s this constant trade-off between available space and desirability of location,” Walker says.

So in the absence of this holy grail, companies must consult with city planners and conduct their own research about traffic patterns to decide where to build their vertiports, the goal being “solving for each region’s individual pain points,” he says.

And those discussions have already led to distinct business models.

Take Archer Aviation of Silicon Valley, which in March announced plans to establish urban air mobility, or UAM, networks within the Miami and Los Angeles metro areas consisting of a yet unspecified number of vertiports and electric takeoff and landing aircraft, eVTOLs. In Miami, Archer wants to begin flights for select routes in 2024 with four-passenger eVTOLs that are still being designed, though Archer in June unveiled a two-seat prototype named Maker that the company plans to begin flight tests with later this year.

The four-passenger eVTOLs would fly routes under 97 kilometers, ideal for commuters catching a ride into their downtown Miami office from their suburban homes or tourists looking for a quick way to visit multiple nearby attractions in a single day.

The Miami network must be built so that “it can be integrated into how people already move around today,” says Brett Adcock, co-founder and co-CEO of Archer with Adam Goldstein. Although the details are still being finalized, Archer plans to offer on-demand eVTOL rides, like Ubers for the sky: Passengers would simply open the Archer app on their smartphone, order an eVTOL and head to the nearest vertiport to board. The eVTOLs in the Miami network would be owned and operated by Archer and flown by company pilots. The company will also sell its eVTOLs to other operators; United Airlines in February announced a $1 billion purchase of 200 Archer eVTOLs for ferrying passengers among its hubs, with the option to buy 100 more eVTOLs in the future.

To figure out where to build the vertiports, Archer engineers are compiling publicly available traffic and location data and plugging it into the company’s Prime Radiant software to simulate likely UAM routes. Plans call for finalizing the vertiport locations in 2022, when construction would commence.

Details including the size and features of Archer’s vertiports are still being decided, but Archer plans to construct all the vertiports for the initial network on top of existing structures, such as the tops of unused parking garages, in high-traffic areas so passengers could easily board and disembark.

“Our aircraft can seamlessly fit in with existing infrastructure — like helicopter landing pads, electric charging stations and local airports — [allowing us to build] our own eVTOL infrastructure based on where people frequently travel,” Adcock says.

And Archer isn’t alone. Joby Aviation of California in May announced a deal with parking garage operator REEF Technology for the exclusive rights to construct the landing pads, charging stations and other needed infrastructure for its vertiports on top of REEF garages, which number some 5,000 across North America and Europe.

Parking garages tend to be situated in high-demand locations, and little new infrastructure would need to be built on the roofs, Joby says. The company is targeting a handful of U.S. cities for eVTOL flights starting in 2024, including Miami.

The Magic City is also a top target for Skyports, though the company won’t say whether it plans to compete to build vertiports for Joby or others planning Florida networks. The relative age of cities including Miami makes the parking garage strategy a good one, says Walker, but could pose a problem for eVTOL companies looking to build networks in historic cities like London or Paris. Few historic buildings have rooftop parking structures that could be converted into landing pads for eVTOLs, Walker says, and tall buildings often create mini wind tunnels that could equate to a severely bumpy ride for passengers.

And, for those skyscrapers, there’s another factor to consider.

“It was a bit of a lightbulb moment when I went to the top of Marina Bay Sands Hotel in Singapore,” says Walker. “It took about 20 minutes to get to the top — that’s 20 minutes added to your journey, which kind of negates some of the benefits of traveling by eVTOL.”

The hotel roof is not among the Singapore sites on which Skyports is considering building vertiports but is across the bay from the full-scale vertiport prototype the company built with Volocopter of Germany in 2019.

Another eVTOL pioneer, Lilium of Germany, the company behind the Lake Nona vertiport plan, hopes to avoid the challenges of retrofitting existing buildings for its in-development Lilium Jets, a prototype of which first flew in 2019. These electric aircraft, propelled by 36 ducted turbofans embedded in the wings and tail, would ferry passengers between brand-new vertiport buildings, to be constructed over the next few years. Lilium in April announced the deal with Tavistock, which will oversee design and construction of the Lake Nona vertiport, the first in a series of hubs that Lilium plans in the U.S.

A 2024 entry-to-service date for that hub is where Lilium’s similarities with Archer end. The company is focusing on building a regional air mobility network for short hops between cities. Because of Florida’s lack of public transit options for trips of this length, “the regional routes are the ones in which you have the greatest time and efficiency gains,” says Alex Asseily, chief strategy officer at Lilium.

Plans call for a network of at least 11 vertiports, including the Lake Nona hub, where up to six passengers would climb aboard Lilium Jets for trips up to 300 kilometers. That’s enough range to connect almost every major city in Florida by eVTOL, including Miami, and to place some 20 million Florida residents within a 30-minute drive of a vertiport, according to Lilium. (But excited travelers should note that although Disney World falls within range of Lilium’s planned network, Asseily says there are no plans to ferry visitors to the park.)

The Lake Nona vertiport offers a rare opportunity to expand a community around the eVTOL infrastructure rather than squeezing it into a historical community, making it more likely that the vertiports would be readily accessible to passengers.

“We fundamentally think eVTOLs will change how people move,” says Ben Weaver, Tavistock’s managing director. “We consider Orlando to be an aerotropolis. For us, it’s all about building cities around modes of transportation, similar to how cities have, historically, been built around ports.”

Lilium’s Asseily says that by 2024, a handful of vertiports will be ready for flights along “a couple of routes,” and then gradually the service will be expanded.

Saving time

If eVTOLs are to be a serious alternative to cars, buses and trains, vertiport networks must be designed for frequent trips, almost akin to that of rail systems. For instance, Lilium plans to operate its Florida hubs as a “very tightly scheduled shuttle network,” Asseily says, with seven- to 12-minute wait times for passengers.

And Archer is betting that the allure of ordering a ride aboard one of its eVTOLs on demand will have Floridians foregoing car trips in many cases, significantly easing road congestion.

Adcock, the Archer co-CEO, likes to use the example of the commute from Miami International Airport to South Beach: Instead of making the 19-kilometer trip by car — which can take over an hour during rush hour — simply order an Archer eVTOL and make the trip in 10 minutes.

But one researcher is skeptical that this promised decrease in traffic congestion will occur, at least initially. City commuters likely wouldn’t notice a reduction in road traffic congestion unless vertiports are at least as ubiquitous as bus or rail stations, says Rolf Moeckel, an assistant professor of civil, geo and environmental engineering at the Technical University of Munich. Moeckel co-authored an August 2020 report in the Council of European Aerospace Societies Aeronautical Journal that found that in cities such as Munich, UAM networks might marginally worsen congestion before making it better.

“When we accounted for what we call access and egress trips — trips from home to the vertiport, and from the vertiport to the final destination — we saw a slight increase in congestion,” he says. “UAM had the counter impact to what we expected, even though Munich has a decent transit system.”

The advent of UAM aircraft presents a once-in-a-lifetime test case for Moeckel and other modelers who must predict traveler behavior for a mode of transportation that doesn’t yet exist. Without observed data, Moeckel conducts interviews with travelers and surveys them about their preferences. Perhaps most importantly, he creates incremental mode choice models, in which data is tapped from an existing travel mode, such as rail, and adjusts it based on factors such as estimated ridership per hour and turnaround time for flights.

“We ran analyses where we increased the price of UAM slowly to see how much it decreased demand, and we also adjusted travel time,” Moeckel says. “By doing a lot of sensitivity analyses, you get a good sense about which dials you need to turn if you want to increase demand for UAM, and what are the driving forces behind UAM.”

When Moeckel and his collaborators conducted these analyses on the Munich metropolitan area, they found that, no matter how they turned the dials, there was a negligible impact on traffic congestion. Moeckel attributes this in large part to the fact that most passengers would still rely on cars or taxis to get to or from the vertiport.

In order for UAM to have a positive effect on urban traffic congestion or the regional economy, a city or region must have the appropriate infrastructure in place to support it.

“That’s not a trivial thing to do,” says Marcus Johnson, a NASA engineer who’s developing automation algorithms to support vertiport scale-up and safety for the agency’s Advanced Air Mobility project. NASA coined the term advanced air mobility to incorporate use cases outside urban environments, such as for longer-range connections between cities or regions, or cargo delivery.

NASA plans to address many of the biggest obstacles to incorporating AAM via ongoing meetings of AAM Ecosystem Working Groups. Since March 2020, NASA has hosted periodic virtual meetings on topics including vertiport operations to draw input from aircraft manufacturers, community members, vertiport developers, regulators and service providers.

“This allows us to address problems related to community integration and really get a good understanding from cities and states and everyone that’s attached to these types of operations,” Johnson says. “What constrains their operations? What constrains what they can do within a city? It’s about marrying these concepts together to have a clear picture of where vertiports can be located. It allows us to see how you measure the impact of operations and how you can report that impact to the wider community.”

AAM for all?

Ultimately, the likelihood of success for Archer, Lilium and their competitors might not be apparent until passenger flights commence from the Lake Nona vertiport and other locations. Both companies believe their targeted price tags are low enough to entice a wide variety of passengers: Archer plans to charge between $3 and $4 per passenger mile, and Lilium is aiming for $2.20 per passenger mile — comparable to the price of ordering an Uber or Lyft. “We can drive the cost down of the seat, make it more accessible, more affordable,” Lilium’s Asseily says. “And so we have more people coming in and out of these towns, and actually we’re making this more available to non-billionaires basically.”

Once again, the Lake Nona community offers a unique chance to gauge success. Perhaps we’ll know that urban and regional air mobility is catching on when the vertiport there becomes just another innovation the city has embraced.

Editor-in-Chief Ben Iannotta contributed to this report.

“It’s important to recognize the opportunity for UAM to connect areas that could benefit from revitalization — especially where other modes of transportation would allow for seamless intermodal connections.”

Laurie Garrow, Georgia Tech’s Center for Urban and Regional Air Mobility

About cat hofacker

Cat helps guide our coverage and keeps production of the print magazine on schedule. She became associate editor in 2021 after two years as our staff reporter. Cat joined us in 2019 after covering the 2018 congressional midterm elections as an intern for USA Today.

About Alyssa Tomlinson

Alyssa has covered unoccupied aircraft systems and transportation engineering for higher education publications.

Related Posts

Stay Up to Date

Submit your email address to receive the latest industry and Aerospace America news.