Stay Up to Date

Submit your email address to receive the latest industry and Aerospace America news.

Few would dispute that electric air taxi developers face headwinds in their efforts to begin flying passengers within a year or two. Mattia Celli and Jan Schmidt of Bain & Company, the Boston-based consulting firm, offer guidelines for success.

Mattia Celli is based in Rome and is a partner with Bain’s Advanced Manufacturing and Services practice.

Jan Schmidt is based in Seattle and is an associate partner in Bain’s Advanced Manufacturing and Services practice and in its Private Equity practice.

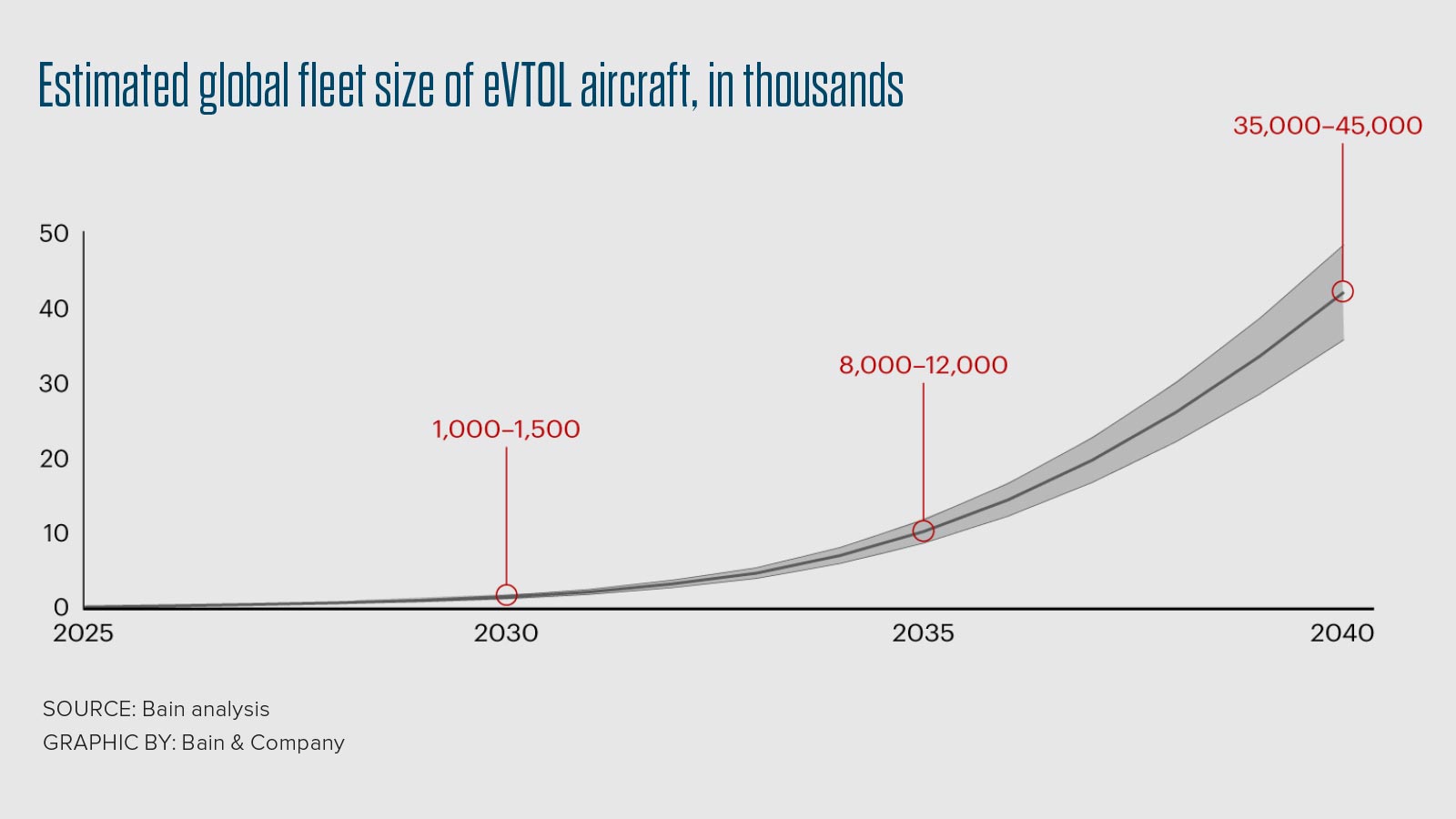

Air taxis, or small electric vertical-takeoff-and-landing aircraft, are poised to create a new civil aeronautics market. Designed to transport passengers and cargo across busy urban regions and in remote areas, they will offer lower costs, reduced emissions and improved safety over helicopters. Analysis from Boston-based Bain & Company shows the global fleet of eVTOLs could grow to 12,000 by 2035 and 45,000 by 2040 [graphic below]. But achieving profitability will be challenging, since even at those numbers, eVTOLs will not amount to a mass-market mode of travel. The price premium for eVTOL flights compared with ground transportation will limit their use to business and mid- to high-income individuals, as well as delivering cargo to hard-to-reach locations or expedited delivery.

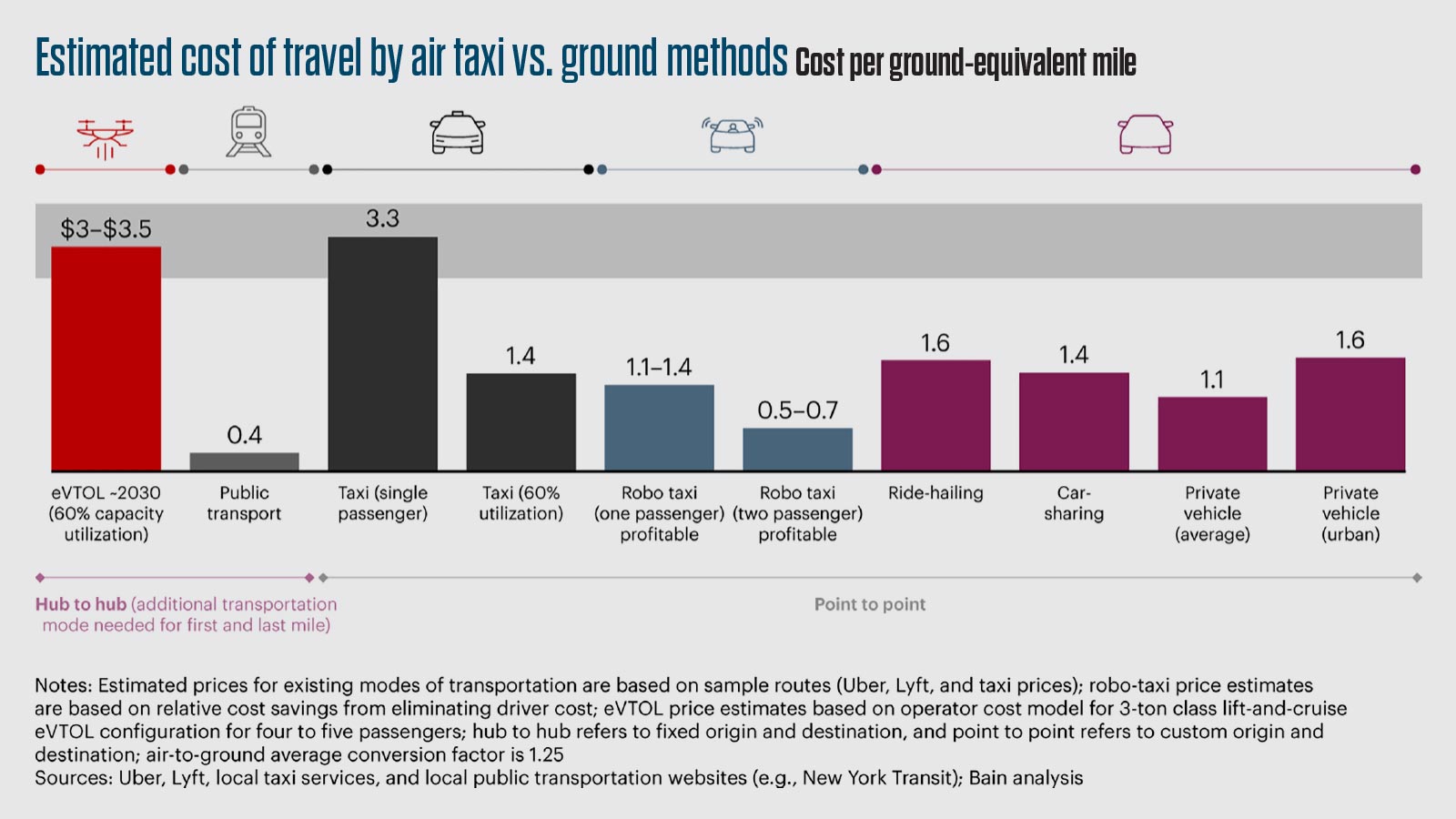

Operators also must ensure that customers don’t spend more time getting to and from transport hubs, ultimately the planned vertiports, than the time they save by flying. By the mid-2030s, eVTOL services will likely face increasing competition from autonomous driving vehicles.

For all those reasons, investors keen to purchase a stake in advanced air mobility companies will need to incorporate significant uncertainty about market growth into their valuations. Bain analysis shows the number of eVTOL aircraft used for passengers and cargo (including hybrid aircraft with vertical or conventional takeoff-and-landing capabilities but excluding unoccupied aircraft) will not surpass 15,000 until after 2035, later than many industry experts are forecasting.

The development of a vibrant market for advanced air mobility depends on multiple factors, including battery technology, new air traffic regulations, infrastructure and aircraft certification and performance. Aircraft certification, for example, is a complex three- to four-year process. The timeline for eVTOLs is likely to be even longer, given new technology and evolving certification requirements.

A few original equipment manufacturers recently achieved significant technological progress, including demonstrating successful transitions from vertical to horizontal flight, a key challenge. These developments mean certification and commercial operation are likely in the next two to three years.

In 2023, FAA published a detailed plan to support eVTOL operations by 2028, defining the steps required for integrating these vehicles into the national airspace. In the initial phase, eVTOLs will comply with most existing communication, navigation and surveillance requirements. While the plan sets a clear path for initial operations, regulators and companies are collaborating to evolve the air traffic management model and develop the technologies needed to ensure safe eVTOL flights in congested airspace.

Today, there are more than 25,000 civil turbine helicopters in service globally, but the market is limited. High operating costs, infrastructure and route limitations — including those due to noise and pollution — and perceived safety issues have deterred wider use. Emerging eVTOL leaders will learn from the constraints on these civil helicopter business models, focusing on safety, infrastructure, aircraft performance and economics.

- Safety. Regulatory bodies and the industry have begun collaborating closely to ensure safety standards similar to those of commercial aviation throughout the entire value chain, from components and aircraft safety requirements to air traffic separation rules. However, many challenges lie ahead as operators prepare for large-scale commercial flight. The industry’s success will also depend on the public perception of eVTOL aircraft safety.

- New infrastructure. Operators may use existing airports and heliports for proof-of-concept operations, but to scale new businesses, they will need a network of well-designed vertiports with charging stations in populated areas. Emerging leaders will choose locations that minimize the commuting distance to vertiports to ensure a high number of potential users.

- Aircraft performance. OEMs are relying on new architectures and technical solutions to design aircraft that can take off and land vertically with electric propulsion — a key challenge — and meet payload and range mission requirements. They have improved flight efficiency (for example, through weight and drag reduction, and by incorporating wings) while minimizing energy-consuming hover time to address the constraint of battery energy density. To build a viable business, operators will need aircraft that have a range of at least 110-130 kilometers and can carry a minimum of three to four passengers.

- Economic viability. Ultimately, travelers will calculate the trade-off between time savings and cost per kilometer traveled, determining the pace of adoption and market size. In most cases, ground transportation will continue to be cheaper, especially as autonomous taxis become a viable alternative [graphic above]. Advanced air mobility companies are forecasting that the price per kilometer traveled will be higher than other competing forms of transportation. As a result, operators likely will need to fund initial financial losses (as Uber and Lyft did) while scaling their businesses.

Three vital components will determine the total cost of ownership: the aircraft acquisition price, maintenance expenses and other operating costs. An eVTOL that seats four or five passengers (excluding multirotor aircraft) is expected to cost between $3 million and $6 million and have an economic life of about 10 years. To be economically viable, operators will need to use the aircraft for at least 1,000 flight hours a year. That benchmark would require fast charging, instrument flight rules that allow aircraft to fly safely in poor weather and at night, and all-weather capabilities.

Maintenance is the Achilles’ heel of today’s helicopter businesses and is often ignored in the prospectuses of OEMs investing in eVTOLs. The maintenance cost for eVTOLs will likely be much lower than for helicopters, given their simpler mechanical architecture (transmission gearing is unnecessary, and eVTOLs have simpler, mechanical flight controls). However, expensive batteries with a limited lifespan are a significant cost factor. Successful OEMs will maximize battery lifespan and improve performance continually.

Operators will also need to keep a tight control on operating costs, including pilot salaries, vertiport fees, insurance and energy. As the market grows, eVTOL pilot costs will be roughly on a par with that for helicopter pilots. Maximizing passenger occupancy and avoiding return trips with empty aircraft will be crucial for operator profitability. The operators best positioned to turn a profit will focus on regions with a combination of high population density, higher income levels, traffic congestion and poor alternative infrastructure for ground transportation on selected routes.

The aerospace industry has begun laying the foundation for a new era of advanced air mobility. OEMs are putting eVTOL aircraft through their regulatory paces, and the first air taxi services are likely to start in the next two or three years, followed by a gradual ramp-up. Safety is the critical entry ticket for every competitor. Future winners will forge a business model well adapted to the constraints of the emerging market and will excel at making the new mode of travel convenient and cost-efficient.

Related Posts

Stay Up to Date

Submit your email address to receive the latest industry and Aerospace America news.