Stay Up to Date

Submit your email address to receive the latest industry and Aerospace America news.

A fundamental issue of physics will prevent it

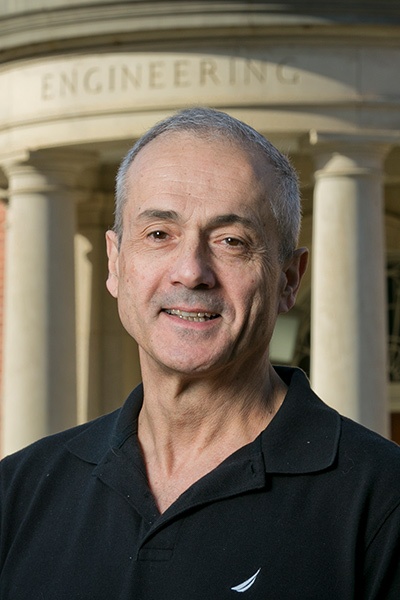

The aviation industry is excited by the prospects of personal aircraft, sometimes called passenger drones or sky taxis, whisking commuters through the sky. Electrical power, automation and safety are obvious challenges to that vision, but there is a more fundamental issue of physics to contend with. Nature theorist and mechanical engineering professor Adrian Bejan explains.

Will personal aircraft be the next big breakthrough as far as popular modes of air transportation go? Will most of us who today drive cars to and from work eventually turn to personal aircraft for our commutes? The answers, simply put, are no.

The problem is that a personal aircraft must expend fuel to get off the ground, to travel a short distance by air, while a runner and an automobile do not have to. Flying is more economical for cruising at longer distances. We see this design clearly in the animal world. When a cormorant needs to travel 10 or 20 meters, it swims. When it needs to travel much farther, it flies and lands kilometers down range. Why, because cruising by air requires less power (useful energy) than moving on water. The energy savings from flying a long distance outweigh the energy penalty of having to rise in the air.

So, flying is for faster travel over long distances. For short distances, the economical movement is on land, and it is slower. We see this in the design of the movement of people among concourses in a large airport, such as Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International. Moving from one concourse to a distant one is accomplished by taking “The Plane Train,” which is analogous to flight. If one wanted to sweep the area fully, that would be accomplished by the short and slow movement, which is by walking along the concourses perpendicularly to the long and fast Plane Train.

That’s my first conclusion, based on years of thinking about the forces that determine how matter, machines and organisms, including humans, will move, or flow, from one place to another, at this moment and into the future. The guiding principle I coined is called the constructal law, a principle of physics I conceived in 1995 to account for design evolution in biology, geophysics and technology. The constructal law accounts for all moving and evolving (morphing) systems, all locomotion, bio and non-bio, human made and not human made, the rivers, the winds, and the animals in the air, on land and in the water.

All moving things evolve toward designs that facilitate the access of the mover through the ambient, by decreasing the effort of pushing the air or water out of the way. For evolution to happen, the design of the moving system must have freedom to change. Nature is endowed with many properties, and freedom is one of them. This is why evolution and the future happen.

There is more to the power to predict the future of any human add-on, such as the personal aircraft. First, some definitions:

Human flight is only a hundred years old, and it is made possible by the oneness of human and machine. The flying person is encapsulated in the flying machine. Without a flying or other kind of machine, the person remains a walker or a runner. Without the person, the machine does not exist. The current physics and biology literature shows that flying “human and machine” specimens (airplanes of many sizes and types, propeller and jet driven) obey the same relationships between speed and size, and between energy use and size, as all the flying animals, insects, birds and bats.

In the physics that unifies all flyers, whether animal or human, “vehicle” means a self-propelled body that has size and weight. The duck, the prehistoric human, the airplane, and the package-delivering drone are all vehicles, and they conform faithfully to the laws of physics. The same is true of all the land and aquatic vehicles, runners and swimmers. Vehicle is a general concept, it is not necessarily made by humans, or with a person inside.

Every vehicle size has its niche. This is evident in animals, where on the same plot on the world map the large animals are few, and the small are many. The large are faster and travel farther than the small. They all move and live together, on the same nourishing land, in harmony. They are like the population traveling through the Atlanta airport, where the large is only one (the train, traveling long), and the small are the pedestrians on the area that hugs the train line.

Niche is also evident in aviation. We know that in aviation the small aircraft outnumber the large aircraft. The same is true of the number of daily flights taken by small aircraft, compared with the daily flights of large aircraft. From the tree outside my window, the sparrows take off much more frequently than the big owl, the sparrows from branch to branch, the owl from tree to tree.

Superimposed, all the niches filled by flyers and other movers constitute a hierarchy, which means few large and many small, together. Hierarchy is a natural phenomenon.

This is why in the future, all moving individuals, groups and populations will continue to exhibit the natural tendency to evolve toward hierarchical configurations, like all the flows in the channels of a river basin, and in all the air tubes in the lung. The aviation equivalent of these hierarchical flows are the flows that constitute the global air traffic system. The big rivers are the long and fast air corridors populated by larger aircraft. The tributaries and branches are the shorter, slower and denser corridors, which are traveled more frequently by more numerous smaller aircraft.

The physics basis for the existence of the “large” is the phenomenon of economies of scale. It is easier to move a unit mass in bulk (along with many other units, on a big river, animal, truck or airplane) than to move it alone. Finding your way out of a crowded arena, it is easier to move with those in front of you (in a conga line) than to elbow your way through all the other disorganized movers who elbow you.

The “small” also exist because of the reality of physics that movement from one place to another must occur within the constraints of a physical area, just as the blood cells inside the body are constrained by the volume in which they flow. Movers cannot fill an area or a volume when they are all big. To fill a space completely, the interstices that exist between the few large are inhabited by smaller and more numerous movers. The spaces between the smaller are inhabited by the even smaller and the even more numerous.

This is hierarchy, and why it is natural, unstoppable. We see it in geophysical movement, animal movement, human social movement (city traffic, global air traffic), everywhere. No flow system escapes from the laws of nature.

With regard to human flight, this evolutionary trend is already evident, even though flying humans are only in the starting blocks of their evolutionary run. The “human and machine species” is a new species, unlike the animal flyers, runners and swimmers. Yet, even as early as now, the aircraft that carry humanity around the globe every day are exhibiting the expected hierarchy, the large are few and the small are many.

The economies of scale phenomenon is also on full display. Large or small, aircraft are evolving toward easier access through the air, which means more economically, more efficiently, with less fuel consumption per passenger and kilometers flown. During the past five decades, the evolution of helicopters has shown a steady decrease in specific fuel consumption. The evolution of commercial jets has been toward less fuel spent for one seat and 100 km flown. On an average, we see a 1.2 percent annual decrease in fuel burn per seat, according to the 2005 study “Fuel efficiency of commercial aircraft — an overview of historical and future trends” by the Netherlands National Aerospace Laboratory.

A new hierarchical design of movement on Earth does not eliminate the existing hierarchical designs of movement. The new hierarchy joins the old, and what works is kept. Animal flyers rose from land but did not displace the land animals. Much earlier, the land animals did not eliminate the swimmers.

And so, personal aircraft will be a new mode of locomotion for some, but not one that will replace the existing modes. This physics is important to know, because the emerging hierarchy can help us predict how few the even bigger models will be and how more numerous the smaller models will be, naturally.

So, as the globe is covered more and more completely by human movement, the smaller patches of the Earth’s surface will be traveled by vehicles that are smaller and more numerous than the vehicles that carry the same human flow over larger areas. Among vehicles that carry a single passenger, the personal aircraft will not eliminate the automobile, the bicycle, the runner and the walker.

Furthermore, the personal aircraft will be considerably bigger than one human body. By invoking the constructal law one can show that the fraction of the mass occupied by the lifting organs in the overall body mass that moves should increase with the body size. This is evident in terrestrial animals, where the lifting organs are the legs.

In animal flyers, the lifting organs are the wings. How they dominate the design is evident, from the hummingbird and the barn swallow, to the condor and the pterodactyl. The reality that goes overlooked is that design is another name for size. The large design is not a blown up version of the small. The large size has its own architecture.

In human flyers, the lifting organ is the aircraft itself, wings and all. Therefore, when contemplating personal aircraft, one should not imagine a blown up version of the humming bird, the toy airplane, and the amazon package with a propeller on top. One should imagine a flying design that is much bigger than the biggest birds, that is a “human and machine specimen” the size of which is mostly machine, not the naked human body. Expending energy getting airborne will not be efficient for travel over the relatively short distance of a commute.

Beyond that, it remains to be seen to what extent the small and many air vehicles will join the small and many land movers. None of these features of movement will deviate from the fewer-and-larger rule.

Personal aircraft and package-delivery drones will not buzz all over our heads. They will fly along hierarchical paths that are defined and regulated (by safety laws and traffic convention, because of the human urge to survive), with rules, rewards and penalties. This hierarchical air design will happen naturally, the same way as the city traffic, the air traffic web and the bird migration corridors.

It’s good to raise questions about inevitability. What is inevitable in design evolution is that evolution is governed by physics principles including economies of scale, hierarchy, the constructal law, and the common sense reality that what works is kept. This means widespread adoption of personal aircraft is not inevitable and, in fact, won’t happen.

Adrian Bejan is a mechanical engineering professor at Duke University in North Carolina and author of “The Physics of Life: The Evolution of Everything” (St. Martin’s Press, New York, 2016).

'When contemplating personal aircraft, one should imagine a flying design that is much bigger than the biggest birds, that is a “human and machine specimen” the size of which is mostly machine.'

Adrian Bejan

Related Posts

Stay Up to Date

Submit your email address to receive the latest industry and Aerospace America news.