Stay Up to Date

Submit your email address to receive the latest industry and Aerospace America news.

Under the Obama administration, NASA loved to deploy the term “green” in project names and on its webpages as a synonym for clean. “Green Aviation: A Better Way to Treat the Planet,” reads the headline of a NASA fact sheet that discusses NASA’s Environmentally Responsible Aviation project, a research effort that the agency wrapped up and wants to follow with a series of X-planes.

With the arrival of the administration of President Donald Trump and its focus on dollars and taxpayers, advocates of government research under the green mantle are shifting to another possible interpretation of green. That’s as in cash, specifically the money that consumers and businesses will in theory save through adoption of electric propulsion on aircraft; safer sustainable fuels for planes and satellites; and more efficient aerodynamic shapes that reduce drag and maximize lift.

With this shift of emphasis toward dollars, I boldly predict that we’ll hear fewer phrases like “environmentally responsible aviation” in the messaging from government agencies. That’s just as well. It was too easy to draw an inference that the aviation sector was somehow irresponsible in the eyes of NASA. I doubt that’s what the agency meant. The best way to clean the planet will be for clean technologies to make competitive sense to businesses, and part of creating that attractiveness will always be research paid for by NASA and other agencies.

The shift in branding does not mean anyone is being disingenuous. The cost-savings argument is nearly always the flip side of the clean coin.

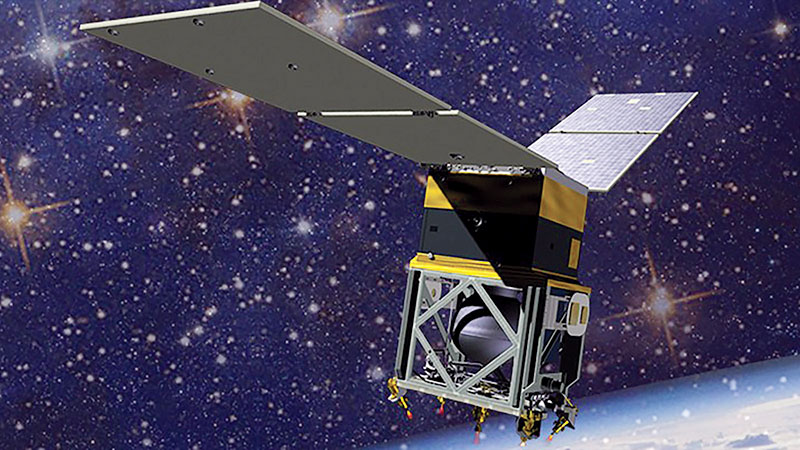

Take for example the Green Propellant Infusion Mission spacecraft that will be launched later this year or early next for NASA. Hydrazine fuel for satellite thrusters is carcinogenic, highly flammable and therefore extremely expensive to produce and load safely into satellites. GPIM, built by Ball Aerospace, will test a nontoxic alternative fuel developed by the U.S. Air Force and components developed by Aerojet Rocketdyne specifically for the new fuel. If GPIM succeeds, for about $45 million (roughly half the cost of a single F-35), all those expensive precautions for handling hydrazine would go away forever.

The faster the satellite industry grows, the faster the cost of that mission will be amortized. Those are the kinds of arguments the new administration probably wants to hear, and there is some merit in the approach. ★

About Ben Iannotta

As editor-in-chief from 2013 to March 2025, Ben kept the magazine and its news coverage on the cutting edge of journalism. He began working for the magazine in the 1990s as a freelance contributor. He was editor of C4ISR Journal and has written for Air & Space Smithsonian, New Scientist, Popular Mechanics, Reuters and Space News.

Related Posts

Stay Up to Date

Submit your email address to receive the latest industry and Aerospace America news.