Stay Up to Date

Submit your email address to receive the latest industry and Aerospace America news.

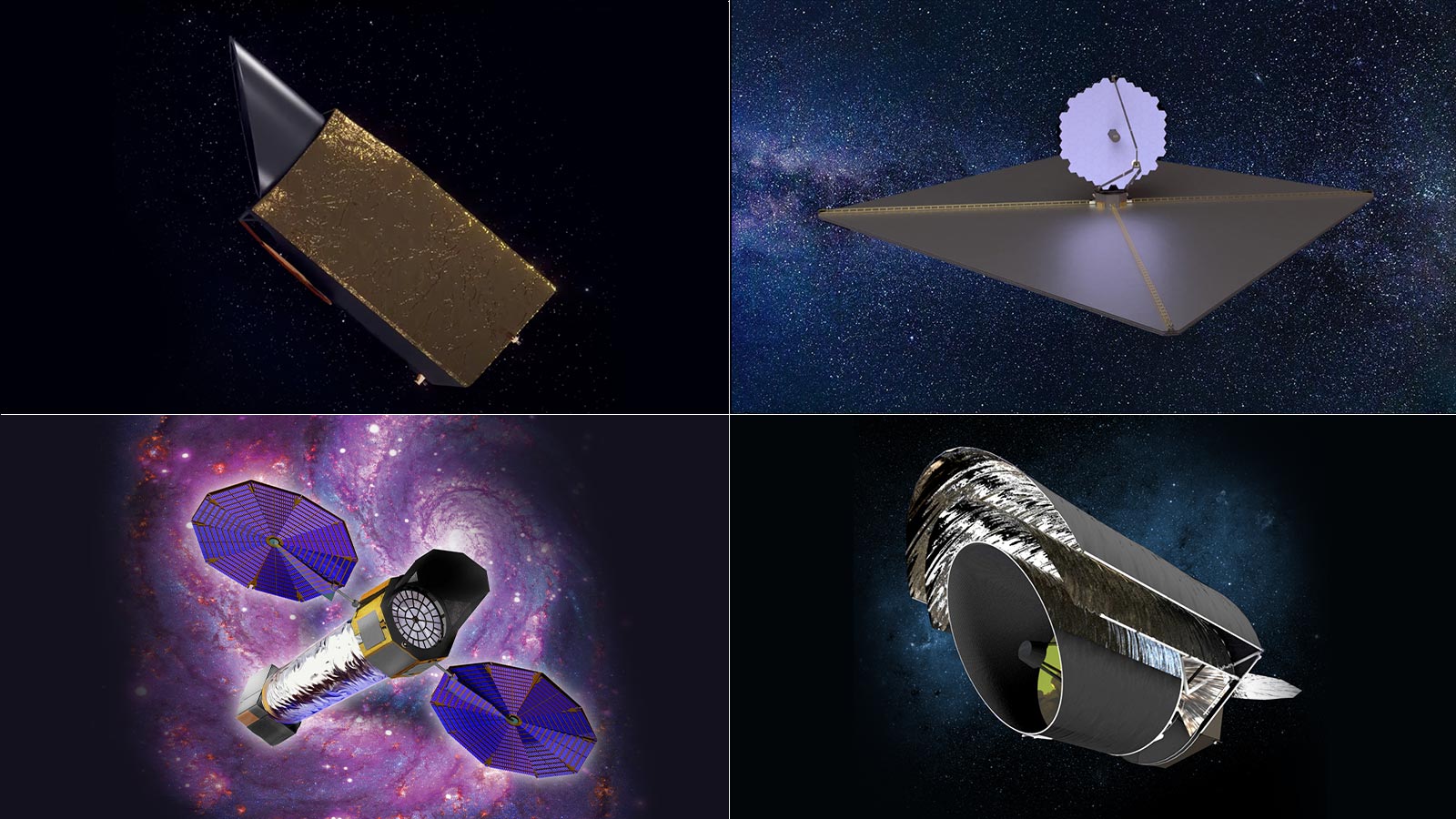

Committee takes inspiration from proposed flagships, but does not select a design

Instead of endorsing one of the four designs submitted by NASA for its next flagship space telescope, a committee of astronomers and engineers wants the agency to start developing the detector and image processing technologies for a series of such telescopes, beginning with one to survey exoplanets for chemical evidence of life. The series would then proceed with others to measure the supernovae explosions and black holes that created the first galaxies, among a long list of goals.

The decadal survey of astronomy priorities published by the U.S. National Academies recommends that NASA create a Great Observatories Mission and Technology Maturation Program “aimed at increasing the cadence of large missions.” Some astronomers say this is a reference to the impact of the cost overruns and delays in developing the James Webb Space Telescope, now scheduled for launch Dec. 18. The U.S. has not launched a flagship telescope since 2003 due in part to Webb’s swollen $8.8 billion development cost.

Ultimately, the decadal committee wants NASA to fund spacecraft inspired by all four of proposed flagship designs, two of which are centered on exoplanets and the others on cosmology.

“What we came up with is our way of ensuring that that will happen,” said committee member Rachel Osten.

Under the strategy proposed in the publicly available report, “Pathways to Discovery in Astronomy and Astrophysics for the 2020s,” NASA would spend the next five years refining a concept for the first of the flagship telescopes, an exoplanet surveyor. Next, by 2025, the agency would pick up research on technologies required for an X-ray telescope that would search for the black holes and supernovae that preceded galaxies, and a telescope that would gaze farther into the infrared than either the defunct Spitzer Space Telescope or the forthcoming Webb would.

The proposed program amounts to a nod to NASA’s four Great Observatories that were launched between 1990 and 2003, each focusing on different wavelengths: the ultraviolet and optical Hubble Space Telescope, Compton Gamma Ray Observatory, Chandra X-ray Observatory and the infrared Spitzer.

The timelines for building those telescopes as well as NASA’s current flagship, Webb, “have taught us that these instruments take decades,” said Gabriela Gonzalez, a member of the decadal committee. In the case of Webb, program officials have said cost and schedule overruns can be partially attributed to the fact that the telescope’s design was not fully settled when a different decadal survey committee 21 years ago chose the basic concept as the top priority for the decade ending in 2010. Webb will reach space 11 years late if all goes as planned.

The committee wants NASA to avoid sliding into another spacecraft program that unexpectedly swallows the astronomy budget for a decade, a history that astronomers have bemoaned. A possible solution could be for NASA to get its field centers, university laboratories and the aerospace industry spun up to address technical challenges including the amazingly sensitive detectors required for the first of the proposed flagships, the exoplanet surveyor. The design for this spacecraft would not be finalized until the required technologies are ready. (Story continues after the box.)

Gonzalez summarizes the strategy like this: “Before committing to spending billions of dollars on one instrument, we spend smaller amounts of money to make sure that technology is matured, and the design is robust and realistic.”

The broad brushstrokes of the exoplanet telescope design laid out by the committee don’t exactly match any of the flagship concepts submitted by NASA in 2018 and 2019. For the exoplanet surveyor, the report recommends a telescope with a 6-meter-diameter primary mirror, a width that falls between those of two of the previously proposed flagships: the Habitable Exoplanet Observatory, or HabEx, and the Large UV/Optical/Infrared Surveyor telescope, LUVOIR (pronounced loov-wahr).

Osten said the intent of the exoplanet recommendation was to find ambitious goals that would fall in between LUVOIR’s price tag of as much as $24 billion and HabEx’s more modest $7 billion anticipated price. NASA would have “maximum flexibility” on the exact design.

“We really tried to give broad advice but not micromanage,” she said, a departure from past decadals whose recommendations have specified the aperture size, wavelength and detailed science goals.

For at least one scientist, the exact size of the recommended mirror was not what mattered most.

“What I really wanted to see was an ambitious, bold vision” like the one the decadal survey laid out, said Scott Gaudi, a professor of astronomy at Ohio State University and one of the leaders of the HabEx study. And while the current HabEx design wasn’t chosen, the only thing better than the decadal recommending his flagship is the committee choosing all of them.

“If we develop those technologies early, you buy down the risk and it makes it even plausible that we could have multiple great observatories flying at the same time, which is multiplicatively better than just having one,” he said.

The decadal committee spent about three years evaluating NASA’s four flagship designs below. While none was specifically endorsed, the survey recommended an exoplanet surveyor with a 6-meter-diameter mirror, placing its collection size in between those of the proposed HabEx and LUVOIR planetary telescopes.

Habitable Exoplanet Observatory (HabEx): A two-part observatory that would consist of a 52-meter-diameter starshade loosely in the shape of a sunflower and a cylindrical main spacecraft equipped with a 4-meter-diameter mirror. The starshade would orbit 75,000 kilometers ahead of the main spacecraft. Once precisely aligned with the main spacecraft and a host start target, the petals of the sunflower would block the blinding light from host star to collect photons from the surrounding exoplanets.

- ORBIT: Second Lagrange Point, L2, 5 million kilometers from Earth and moon in the opposite direction of the sun.

- MISSION DURATION: 5 years, but enough detector life and station-keeping fuel for 10 years.

- COST: $7 billion over 10 years.

- NOTABLE: At 4 meters, the primary mirror in the main spacecraft would be the largest monolithic primary mirror launched to space.

Lynx X-ray Observatory: A cylindric telescope that would gather the lingering X-ray photons from hot gases ejected by the exploding supernovae that birthed the first stars and galaxies. In fact, Lynx would peer back in time even farther than the James Webb Space Telescope.

- ORBIT: L2

- MISSION DURATION: 5 years, but with enough station-keeping propellant for 20.

- COST: $4.8 billion to $6.2 billion

- NOTABLE: The name is a nod to the Academy of the Lynx scientific society where Galileo was a member.

Large UV/Optical/Infrared Surveyor telescope (LUVOIR, pronounced loov-wahr): A spacecraft carrying a massive, segmented mirror in the style of Webb. The mirror would collect photons from Earth-like exoplanets to determine their atmospheric composition. Two competing options were proposed, LUVOIR A and B.

- ORBIT: L2

- MISSION DURATION: 5 years

- COST: $18 billion to $24 billion for the LUVOIR A version with a 15-meter-diameter mirror; $12 B to $18 B for LUVOIR B, the version with the 8-meter-diameter mirror.

- NOTABLE: The 15-meter mirror in the LUVOIR A design would be about the diameter of a Ferris wheel.

Origins Space Telescope: A barrel-shaped telescope with multiple cryocoolers that would chill the 5.9-meter-diameter primary mirror and far-infrared detectors to 4.5 kelvins (minus 268 degrees Celsius). The telescope would soak up infrared waves from the first galaxies with finer resolution than Webb.

- ORBIT: L2

- MISSION DURATION: 10 years

- COST: $6.7 billion to $7.3 billion

NOTABLE: Colder operating temperatures than Webb, whose single cryocooler chills the camera and spectrograph Mid-Infrared Instrument to 7 kelvins (minus 266 degrees Celsius).

About cat hofacker

Cat helps guide our coverage and keeps production of the print magazine on schedule. She became associate editor in 2021 after two years as our staff reporter. Cat joined us in 2019 after covering the 2018 congressional midterm elections as an intern for USA Today.

Related Posts

Stay Up to Date

Submit your email address to receive the latest industry and Aerospace America news.