Stay Up to Date

Submit your email address to receive the latest industry and Aerospace America news.

Six years and four missions in, has the program lived up to its promise to deliver more science to the lunar surface at a lower cost?

The shadow of the Blue Ghost lander on the lunar surface. Credit: Firefly Aerospace

With two launches in the books and potentially two more before year’s end, 2025 could be the year of judgment for NASA’s Commercial Lunar Payload Services program.

The premise of this initiative, created in 2019, was that awarding companies “task orders” to design, build and deliver robotic landers to the moon would allow a higher flight cadence at a lower cost compared to the traditional NASA contracting approach. In the longer-term, CLPS would help spawn a larger lunar space economy and contribute to NASA’s efforts to put humans on the moon and Mars.

Has it succeeded on those fronts? Six years in, the verdict isn’t unanimous, but for the former NASA executive who started the program, the answer is a resounding yes.

“If you look at the: ‘Well, did it make sense to build this new system?’ the answer has to be a wholehearted ‘yes,’” said Thomas Zurbuchen, the astrophysicist who led NASA’s Science Mission Directorate from 2016 to 2022.

Based on my review of task order announcements and other public documents, NASA has awarded roughly $1.5 billion in firm-fixed-price contracts to a handful of vendors to conduct 12 missions through 2028, and the agency told me it plans to spend up to another $1.1 billion. Of the four missions completed to date, only Firefly Aerospace’s Blue Ghost in March was deemed by NASA and the vendor to be a complete success. Those might not seem like great odds, Zurbuchen acknowledged, but consider that NASA’s portion of those four missions was a combined $386 million. In contrast, he estimated that a single lunar mission would have cost up to $2 billion under the agency’s traditional management approach.

For a fraction of the cost, “we created the same success, roughly,” said Zurbuchen, who now serves on Firefly’s board and said he is working with another CLPS vendor, Intuitive Machines, on non-CLPS-related projects.

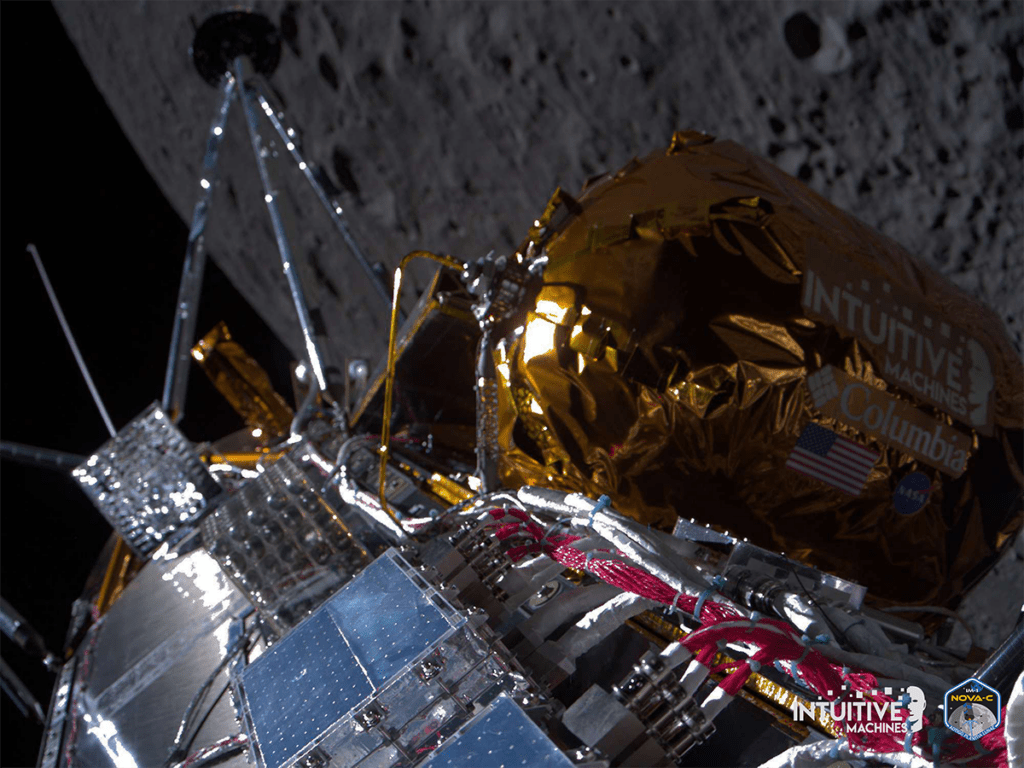

That’s not to say everything has gone according to plan. The first CLPS missions took place four years after NASA’s original target, and with mixed results. In January 2024, Astrobotic’s Peregrine lander sprung a leak while in orbit, and the company called off the landing after determining not enough propellant remained to reach the lunar surface. A month later, Intuitive Machines became the first company to land a privately developed spacecraft on the moon, but the Odysseus lander completed its weeklong mission on its side after breaking one of its legs. The company’s second lander, Athena, met a similar fate a year later, tipping over inside a crater near the lunar south pole that prevented it from transmitting more than an hour’s worth of data.

Intuitive is incorporating lessons from both landings to ensure its third one, scheduled for 2026, is a success. In the near term, two more CLPS landings are scheduled for later this year: Astrobotic’s Griffin-1 and Blue Origin’s Blue Moon Mark 1, though neither company has announced a more specific date.

A new mindset for a new market

In Zurbuchen’s view, CLPS represents more than just a new management approach — it’s an entirely different mindset around what constitutes success.

“The standard culture at NASA is toward perfectionism,” he said. “That’s not bad or good, it’s just what the agency is.”

This failure-is-not-an-option approach dates back to Apollo 13’s near brush with disaster and drives the agency to “understand each and every risk, and we hammer down each and every risk.” That’s a great fit for high-risk, high-reward missions where human lives are at stake, he notes, but also drives up cost and development timelines.

By contrast, Zurbuchen designed CLPS so that vendors had a higher degree of decision-making authority, which in theory would allow for speedier development times at lower costs. Another notable change was the mindset, he said: “actually accepting failure; failure being part of the necessary development, which is much more iterative.”

This is similar, he noted, to Space X’s development model for its Starlink satellites and Falcon and Starship rockets. And because NASA is neither the owner or sole future customer for these landers, CLPS could help foster “an entrepreneurial ecosystem” in the U.S. economy beyond the business of moon landings.

“Every one of these companies has other business branches they developed, but around the core business, which initially was landing,” Zurbuchen said.

He pointed to the combined market capitalization of more than $10 billion for the publicly traded Firefly, Intuitive Machines and ispace of Tokyo, whose U.S. subsidiary is providing an APEX 1.0 lander for a planned 2027 CLPS landing in partnership with Draper Laboratories. By demonstrating energy production, or water electrolysis, or helium-3 mining, or other potential commercial activities on the moon along with reliable transportation, the companies can convince investors that the opportunities are real, said Ron Garan, chairman of ispace U.S. Its parent company last year signed agreements to collaborate on future mining endeavors with lunar prospecting company Magna Petra, in March for demonstrating lunar water processing with Kurita Water Industries and in May for demonstrating lunar water extraction with Takasago Thermal Engineering Co.

Additionally, ispace U.S. announced agreements in 2024 for collaborating on laser-delivered solar power technologies for the moon with Volta Space Technologies and in April for demonstrating nuclear power on the moon with Zeno Power Systems Inc.

“That’s where the development of the moon can take off exponentially,” he said. “ispace exists to assist in the creation of the infrastructure necessary to enable a permanent significant presence on the moon.”

Another early mark of success for CLPS has been the increased opportunities for the science community to land payloads on the moon, said Tim Crain, chief technology officer and co-founder of Intuitive Machines. “It opens up and democratizes space in a way that a handful of very large, very expensive missions would restrict to a small set of scientists.”

CLPS has established an “incredible pace” for lunar missions that didn’t previously exist, said Crain. “Five years ago, there was no commercial lander, and in the last year and a half, we’ve flown two.”

Lingering questions

But not everyone is convinced that the CLPS model has proved itself.

“We don’t know if CLPS works yet as a concept,” said Casey Dreier, chief of space policy for the Planetary Society, a California nonprofit that advocates for space exploration. “We will get a sense in the next few years as some of these companies make their second or third attempts if they can find more viable business models beyond NASA. That’s probably unlikely, but not obviously impossible, and if they could improve the reliability, that’s the key.”

That’s because other customers are likely to have a lower tolerance for failure than NASA, he said. For instance, a 20% failure rate may still be too high for a lunar business model to work: “How do you insure for that financially? Nothing of huge value will ever go on those things.”

He added: “This is why, classically, NASA pays for that 99.999% reliability factor. You pay for each significant digit you add to that reliability, because if you’re sending something really valuable, you won’t have the chance to make it again.”

Without NASA’s ongoing financial support, Dreier said, he doesn’t see enough private funding available to sustain these lunar landing companies.

“SpaceX has warped the expectations of the policymakers to some degree, to say that ‘Well, of course commercial companies will succeed and will have, as a consequence, this radically new capability that will be leveraged in X, Y and Z,’” he said, referring to how SpaceX has secured a variety of customers outside NASA for its launch business.

“I’m not saying it won’t happen, but I’m saying it’s probably less likely to,” Dreier said.

If Zurbuchen could do it over again, he said he would make some changes to CLPS, including having NASA provide more technical support to the vendors. “We stepped back and said, ‘You try, and good luck,’ as opposed to saying, ‘Hey, we’re really experienced; let me help.’”

He said he also wishes CLPS had been set up to give multiple chances to the scientists with experiments aboard the landers. Now, if a vehicle doesn’t make it to the lunar surface, there are no second chances for the experiments on board to fly again.

Despite this, he said aspects of the CLPS approach could be applied to future NASA Mars programs and other endeavors — but not without thorough review by the agency and outside experts.

“The most important question is: What did we learn from it in a way that makes us all better as an industry, as an agency?” he said.

About Keith Button

Keith has written for C4ISR Journal and Hedge Fund Alert, where he broke news of the 2007 Bear Stearns hedge fund blowup that kicked off the global credit crisis. He is based in New York.

Related Posts

Stay Up to Date

Submit your email address to receive the latest industry and Aerospace America news.