Stay Up to Date

Submit your email address to receive the latest industry and Aerospace America news.

LONG BEACH, Calif. — Journey’s “Don’t Stop Believin” is blaring from a radio when I enter the cavernous factory here, where Virgin Orbit is building the first copies of LauncherOne, a line of expendable rockets intended to give satellite owners something they’ve never had before: Launch vehicles made specifically for their needs. Today, small satellites are typically squeezed aboard larger rockets as secondary payloads, which leaves them beholden to the schedule of the primary customers.

With lathes and mills whining and humming in the background, President Dan Hart and Vice President for Special Projects William Pomerantz show me a hybrid 3-D printing machine that’s the size of a bus. It’s considered a hybrid because it marries additive manufacturing with the conventional “subtractive” technique of machining away material, a final step that remains necessary for many 3-D-printed parts.

“You put in a block of metal and get out a fully formed and machined part,” explains Hart. “It’s mind-blowing.”

Virgin Orbit is the first aerospace company to manufacture parts with the Lasertec 4300 3D built by DMG Mori, a Japanese firm known for advanced metal cutting tools. The company is now experimenting with how to incorporate the device in its manufacturing process.

British billionaire Richard Branson established Virgin Orbit in March to run the satellite launch business separately from his Virgin Galactic company. Hart joined as president that same month after a 34-year career with Boeing Government Space Systems, which builds satellites and launch vehicles for national security agencies.

Virgin Orbit has picked up where Virgin Galactic left off on a campaign to incorporate as much automation as possible in manufacturing, and the Lasertec 4300 is part of that initiative.

The company calculates that it must manufacture two dozen of the 21-meter-long, 25,000-kilogram LauncherOne rockets a year to meet the high demands of NASA and companies such as satellite internet startup OneWeb, which like to buy launches a half dozen at a time. The company will likely need every bit of this facility, which at 16,500 square meters is about the size of two football fields and where nearly 300 engineers and technicians work.

Engineers plan to start LauncherOne flight tests either late this year or early next year, and they are nearly finished building the major subsystems for the first tranche of rockets. These subsystems include the main stage Newton 3 and upper stage Newton 4 engines, which, in an unusual strategy, are being made in-house here rather than by a vendor.

Something else unusual is the layout of the facility. Adjacent to the enormous floor is a cramped, open office space with tightly spaced rows of desks for senior executives and engineers. It doesn’t look like a place where someone would want to sit for very long.

“That’s intentional,” Pomerantz says. “We want engineers to spend their time out here on the shop floor. We don’t want a situation where our avionics engineers don’t talk to our propulsion and structural engineers who don’t talk to the salespeople. When they bump into each other as they get coffee in the morning, they have impromptu discussions we find really useful.”

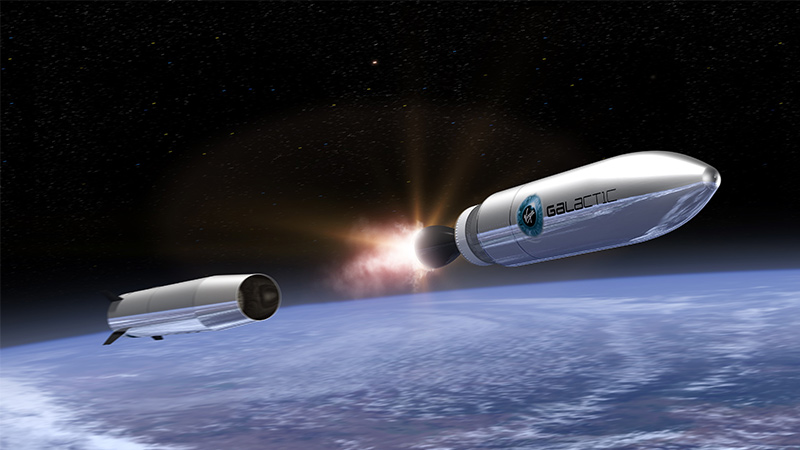

Virgin, in fact, has never been afraid to make adjustments. When Branson founded Virgin Galactic in 2004, plans called for carrying expendable rockets one at time to a high altitude on the same WhiteNightTwo carrier plane that will, on other missions, carry and release SpaceShipTwo, a piloted, reusable rocket plane that will blast tourists to the fringes of space.

Virgin changed course in 2015 after surveying customers and finding their satellites were getting larger and they planned to build large constellations of satellites. The company bought a used Boeing 747-41R airliner from Virgin Atlantic and L-3 Platform Integrations is reinforcing the plane to carry a LauncherOne rocket. The 747 will raise payload capacity to 300 kilograms to sun synchronous orbit, compared to 125 kilograms for WhiteKnightTwo. Plus, Virgin Orbit won’t have to share a plane with Virgin Galactic.

There have been other strategic shifts too. Originally, Virgin wasn’t planning to build all major rocket components in-house. Engineers investigated whether they could buy engines from a vendor, but they quickly realized that wouldn’t mesh with their business plan. “By aerospace standards, we are building at a really high rate,” Pomerantz says. “A lot of these [engine manufacturers] are used to supplying customers that fly three rockets a year. When we said, ‘We want 24 engines, some spares and more for testing,’ they would say, ‘That’s a decade of production for us.’”

Cost was another concern. Some engines on the market would have cost more than the $12 million to $15 million Virgin Orbit plans to charge customers per launch. Hence the investment in time-saving factory equipment, like the Lasertec 4300 3D printer.

Today, it takes Virgin Orbit about nine months to manufacture a Newton engine the conventional way of grinding down the metal and sending the engines to various suppliers for plating and finishing. With the Lasertec 4300 3D, Virgin Orbit thinks it can cut the time to build an engine down to a month or even less.

“We are not counting on it working for our first mission or our second mission, but eventually this will allow us to go a lot faster and save a lot of money,” Pomerantz says.

“We want engineers to spend their time out here on the shop floor. We don’t want a situation where our avionics engineers don’t talk to our propulsion and structural engineers who don’t talk to the salespeople. When they bump into each other as they get coffee in the morning, they have impromptu discussions we find really useful.”

William Pomerantz, Virgin Orbit vice president for special projects

About Debra Werner

A longtime contributor to Aerospace America, Debra is also a correspondent for Space News on the West Coast of the United States.

Related Posts

Stay Up to Date

Submit your email address to receive the latest industry and Aerospace America news.