Augmented reality is helping NASA get back to the moon

By Cat Hofacker|August 24, 2021

Site visit: Lockheed Martin Space

★ Click at right to open this story’s Knowledge Guide entries.

★ Click star at right to open Knowledge Guide.

COLORADO SPRINGS, Colo. — The tale of the early days of the U.S. space program can’t be told without mentioning Lockheed Martin’s Littleton campus, where technicians of what was then the Martin Company in the 1950s constructed the Titan rockets that launched military satellites and later all of NASA’s Project Gemini spaceflights.

“There’s a lot of history here,” said Dave Buecher, a mechanical engineer at Lockheed Martin and one of the employees that I and a handful of other reporters met during our tour of the campus on Monday before the Space Symposium.

Flash forward to present day, and much has changed: For one, the Titan manufacturing building has been converted into a production facility for the aeroshells of NASA’s robotic Mars spacecraft and the heat shields of the Orion crew capsules that will protect astronauts as they plunge back to Earth through the atmosphere.

The campus itself has grown into a sprawling collection of buildings on 4,600 acres nestled against the red rocks of the eastern slope of the Rocky Mountains, a 90-minute (and very bumpy) bus ride almost due north from Colorado Springs.

At least one thing hasn’t changed since the Eisenhower era: Lockheed Martin is betting that the spacecraft in various stages of development across the campus will cement its place in shaping the next chapter of U.S. human spaceflight program.

And this time, Lockheed Martin is relying on a set of digital tools, especially augmented reality, or AR, to reduce the time it takes to design and build spacecraft.

Take NASA’s Orion crew capsules, which Lockheed Martin has been working on since 2006 and that must ferry NASA astronauts to lunar orbit and back starting in 2023 under the Artemis program.

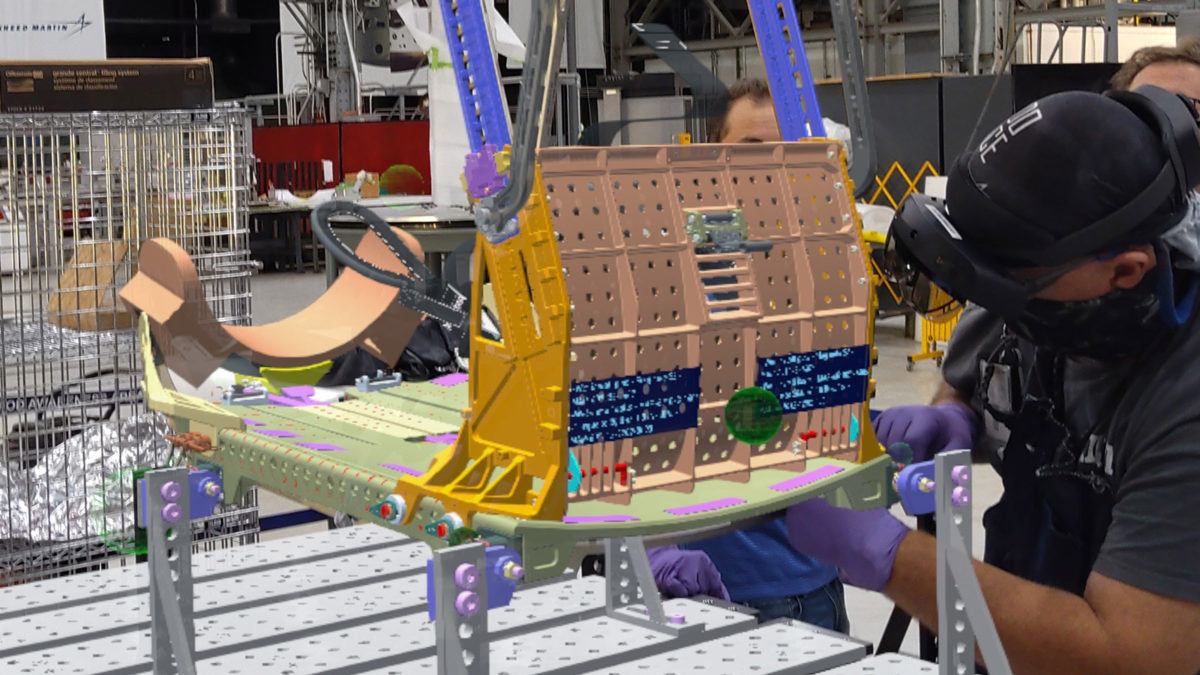

To aid technicians in installing such features as the crew seats, Lockheed Martin turned to augmented reality beginning with the Orion capsule for Artemis-2, the mission to send four astronauts on a slingshot journey around the moon and back home. The process began by uploading Orion blueprints to Unity 3D, the AR software from Unity Technologies of San Francisco. Designers and engineers donned Microsoft HoloLens 2 headsets and looked inside the Orion capsule. They saw markings overlaying the exact spots on the flight hardware where they needed to install components, including the hundreds of fasteners that would attach the seats to the floor of the spacecraft.

“It’s kind of like a YouTube how-to video,” but one in which the software provides visual cues that “guide you through precisely,” said Darin Bolthouse, who oversees the Collaborative Human Immersive Lab, where employees learn how to apply AR in their work.

I saw the process for myself later in the tour, in the old Titan rocket building where technicians are currently assembling the heat shield for the Orion spacecraft for Artemis-3, the historic return to the moon planned for 2024 in which an Orion must deliver the two astronauts to the craft that will take them to the surface. Awaiting my turn with the headset, I stood in the cleanroom, under a table-like platform supporting a critical piece of the flight hardware: a partially constructed titanium skeleton that will support the smooth outer dome of the heat shield consisting of dozens of layers of composites. This is where, in future steps, technicians will fasten the skeleton’s joints together. I secured the headset behind my head and snapped the goggles down, then looked up to see a literal rainbow: Translucent lines of colors were laid over the silver ridges of the heat shield, with combinations of letters and numbers next to each joint. Those denoted a different step of installation. I looked down toward the floor, and a block of text popped up, providing extra detail about each particular step.

Before this AR process, technicians would measure and mark the roughly 1,000 places along the heat shield that needed a fastener. With the AR headset, “this shows you precisely where they go,” Bolthouse said.

Once technicians finish bolting the titanium skeleton to the the heat shield, they’ll ship the assembly to NASA’s Kennedy Center in Florida, where technicians will install blocks of thermal protective materials to the outside of the dome and later bolt it to the Orion crew and service modules. Next up will be attaching Orion to a Space Launch System rocket and rolling it out to the launchpad, where if all goes as planned the Lockheed Martin employees back in Colorado will see their years of work pay off.