One woman’s Apollo story

By Debra Werner|July 16, 2019

Fifty years ago today, Sheryl Watson, then a computer programmer at Bellcomm Inc. in the Washington, D.C., area, gave a very specific direction to the movers who had arrived in the morning to help her and her husband relocate to a new house: Load everything in the truck except the television.

She needed to watch the Apollo 11 liftoff.

Watson was among a small group of women out of an estimated space workforce of 400,000 who provided computation, programming and administrative services for the Apollo missions.

Her story, I discovered, is typical in some ways, but with a surprising twist. Her work on Apollo would turn out to be a relatively brief chapter in a long technical career.

Watson was hired by the subsidiary of Bell Labs in 1965 as a technical staff member, which meant she was a programmer. Women were infamously underrepresented in the workforce overall, but at the company Bell had formed to test Apollo software, half of her programming colleagues were women. One of Watson’s roles was to make sure NASA’s trajectory computing code would not subject a returning Apollo capsule to more than 8 Gs of force or send it skipping off the atmosphere.

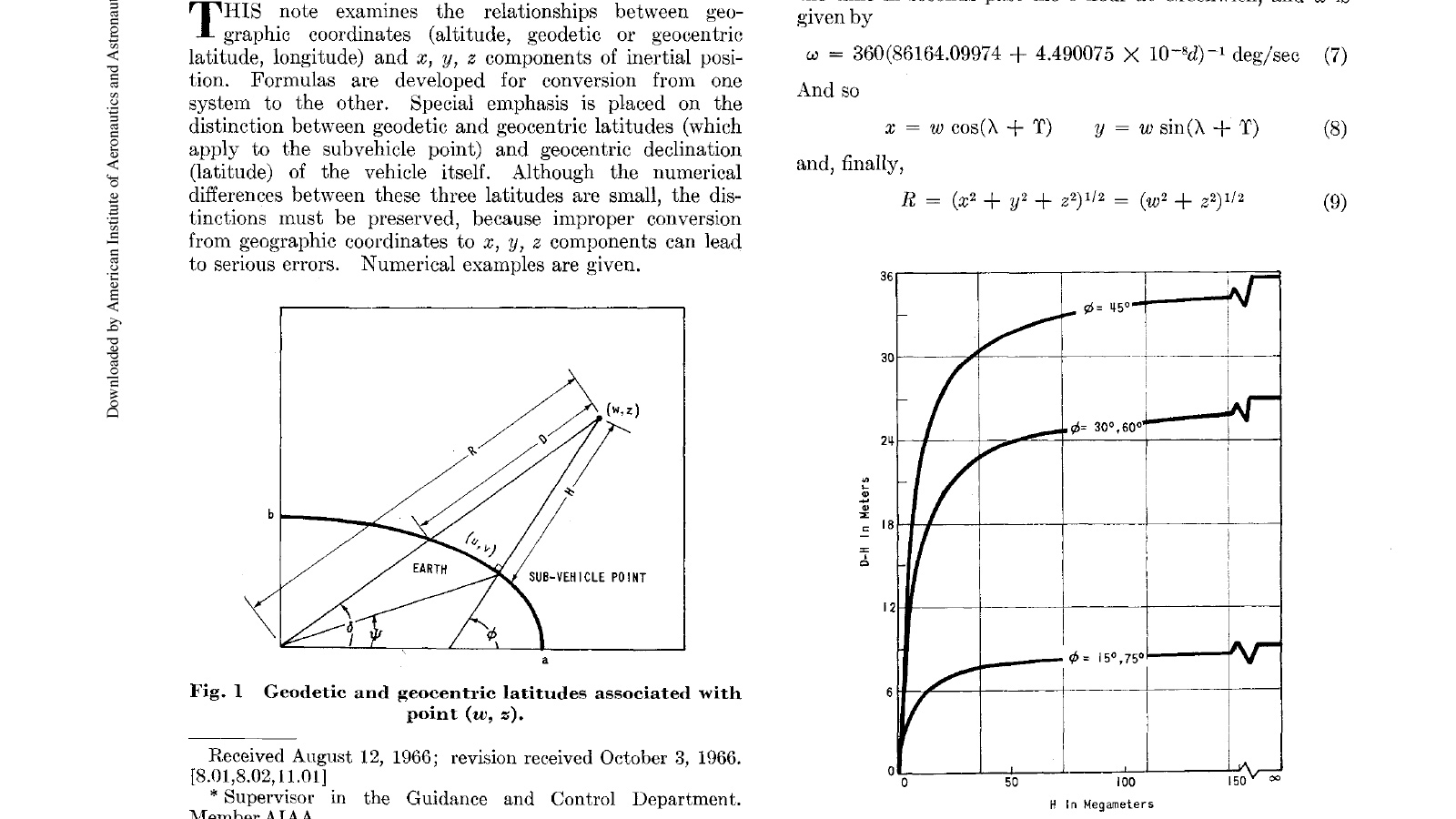

I reached Watson at her home in Vienna, Virginia, after she contacted AIAA seeking to show her grandchildren tangible evidence of her contribution to Apollo. Watson and her boss at Bellcomm, Gordon Heffron Jr., wrote the 1967 paper, “Relationships between Geographic and Inertial Coordinates,” which appeared in AIAA’s Journal of Spacecraft and Rockets. The paper warned NASA that when planning a trajectory, “improper conversion from geographic coordinates to x, y, z components can lead to serious errors,” even though the numerical differences are small.

Since Earth is not a perfect sphere, there’s a difference between a spacecraft’s altitude as measured by a line perpendicular to Earth’s surface, called the geodetic position, versus a line directly from the spacecraft to Earth’s center, called the geocentric position. “My supervisor thought the numbers were so big that the computer was having trouble,” recalled Watson. She confirmed the accuracy of the computer program manually, including taking the square root of a 15-digit number, and published the results in the paper.

After that, “measurements were taken perpendicular to the Earth because that is the easiest to do,” Watson said. “It is much harder to determine that your line of sight is going to extend to the center of the Earth.”

On later Apollo missions, Watson worked on a project to show astronauts what they would see out the window during the lunar landing. Standing at a light table, she hand-shaded computer-generated lunar maps to depict the portions that would be in shadow.

Here’s what surprised me: Watson’s contributions to the space program ended after the last Apollo mission in 1972 when Bellcomm closed its office. She went on to work for a contractor for the Department of Housing and Urban development, programming loans, which she said “turned out to be a lot more challenging than orbital mechanics.”

Related Topics

Apollo 50th Anniversary