NASA’s search for life on Europa, Enceladus just got easier

By Tom Risen|April 25, 2017

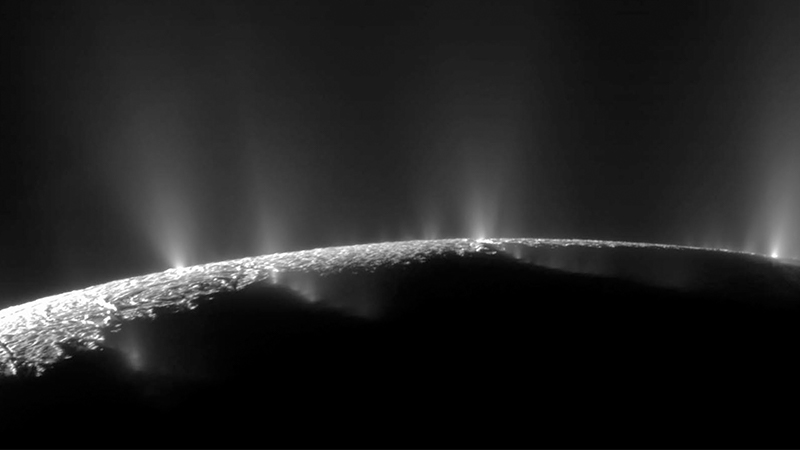

NASA on Thursday said data collected by the Cassini spacecraft show a strong possibility that the ocean beneath the icy surface of Saturn’s moon Enceladus is capable of supporting microbial life. Also, images of Jupiter’s icy moon Europa taken by the Hubble Space Telescope suggest that at least one geyser could exist there too, offering a potential target for the planned Europa Clipper mission when it flies by during its orbiting of the gas giant.

The press conference on the “oceans beyond Earth” research initiative comes as the NASA-funded Jet Propulsion Laboratory is in the design phase of its Europa Clipper mission and testing political waters to propose new missions to explore the outer planets. If microbes were ever discovered in the oceans of Enceladus or Europa, it would not only prove life is possible on other planets, but give scientists new insights into theories about how life evolved even in the ocean depths of Earth where no sunlight reaches.

The Cassini spacecraft during its multiple orbits around Saturn flew through plumes of water ice and vapor that spout from cracks in the ice of Enceladus. Cassini’s Ion and Neutral Mass Spectrometer detected hydrogen, carbon dioxide and methane. The disequilibrium of these molecules in the plume indicates the methane could have been created by methanogenesis, a process that supplies energy to microbes in Earth’s deep oceans in the absence of sunlight, says Hunter Waite, who is one of the co-authors of the Enceladus research published today in Science magazine.

This indicator of chemosynthesis is a tantalizing sign that the Enceladus ocean can support some kind of microbial life, says Waite, the Cassini Ion and Neutral Mass Spectrometer team lead at the Southwest Research Institute. The spectrometer wasn’t designed to measure the content of the geyser, but its ability to measure ions gave scientists the chance to detect the molecules in the vapor.

“We did not find inhabitants, but we have pretty much nailed the case that its oceans have habitable conditions,” says Waite.

Scientists suspect Europa might have one or more geysers, which has some scientists eager to send the Europa Clipper spacecraft through one more of them, if they exist. Comparing Hubble images of Europa to thermal scans made by the Galileo probe, which orbited Jupiter until 2003, suggests there could be a geyser spouting just south of the equator on Jupiter’s moon, says William Sparks, an astronomer with the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore. It’s unclear whether this plume could be spouting from the ocean, as in the case of the geysers on Enceladus, but the upcoming Europa Clipper spacecraft will have the chance to find out using its next generation version of the spectrometer on Cassini, Sparks explains. If NASA can confirm this plume’s location, engineers will have to determine how often the geyser spouts into the atmosphere, and whether it is thin enough for Clipper to fly through safely.

The findings from Europa and Enceladus will likely spur debate about the best ways to explore the outer planets for evidence of life, he says. A launch date has not been set for the Europa Clipper spacecraft, which is still in the design phase, but Congress and NASA have mentioned 2022 as a possible date. The Trump administration’s proposed budget for 2018 does not include funds for a Europa lander that some scientists and lawmakers had favored.

“Looking beyond Europa Clipper, there is discussion of a Europa lander, but we don’t know if it’s going to happen or not,” Sparks says. “There is also consideration of smaller missions for probes to explore the plumes on Enceladus.”

Detecting the molecular conditions that could support life in the ocean of Enceladus required some improvisation by the Cassini team. NASA didn’t know the moon spouted geysers when Cassini launched in 1997, and made the discovery after the spacecraft reached Saturn’s orbit in 2004. Fortunately, its Ion and Neutral Mass Spectrometer was capable of measuring the content of the plumes by separating molecules based on their mass, which made it possible to identify hydrogen in the plume. The titanium chamber of the spectrometer, however, can create an oxide layer that reacts with water vapor specimens from the plume to accidentally create hydrogen. Waite says he and his team made measurements to detect hydrogen using the spectrometer’s open source mode to minimize the chance of this reaction confusing the results.

The Southwest Research Institute is building a next generation version of this spectrometer for the Europa Clipper, called the Mass Spectrometer for Planetary Exploration, which Waite says could fly through plumes on Europa, and measure molecules that would provide clues to the microbial habitability of Europa’s ocean. Findings from Waite’s study will inform how the new spectrometer is built, which may include building its chamber with a less reactive material than titanium.

Cassini is preparing for its grand finale that will end its two decades of flight with a crash into Saturn. Cassini is on track for a final flyby of Titan on April 22, and on April 26. That trajectory will point it toward Saturn’s rings, where between May and July it will perform tests on the dust and ice particles in the rings, including bouncing radar off the particles and sending radio transmissions through them toward Earth. NASA plans to steer Cassini directly into Saturn on Sept. 15 before it starts running low on fuel, giving scientists the chance to make the closest measurements ever of the gas giant’s atmosphere before the spacecraft is lost.

“We did not find inhabitants, but we have pretty much nailed the case that its oceans have habitable conditions.”

Planetary scientist Hunter Waite on the Enceladus research