NASA: Partnership Needed to Send Humans to Mars

By Tom Risen|May 11, 2017

Getting humans to Mars will require NASA to work with industry and international partners, perhaps even China to the degree U.S. law and policies permit, speakers at the Human to Mars Summit in Washington, D.C., said Tuesday.

NASA Acting Administrator Robert Lightfoot used his keynote address to rally support to achieve what he called “the generational goal of bringing humans to Mars” and “humanity’s next giant leap.”

Broad collaboration would ensure a “civilization level impact” from the mission, he said. Also, numerous technological breakthroughs would be made during preparations for the Mars journey, and Lightfoot said the prospect of these should also motivate nations and companies to coordinate. Discovering life on Mars would be “a fundamental change” for humanity, he added, and this possibility should be another motivator.

“It’s going to take all of us — it’s going to take all our industry,” Lightfoot said.

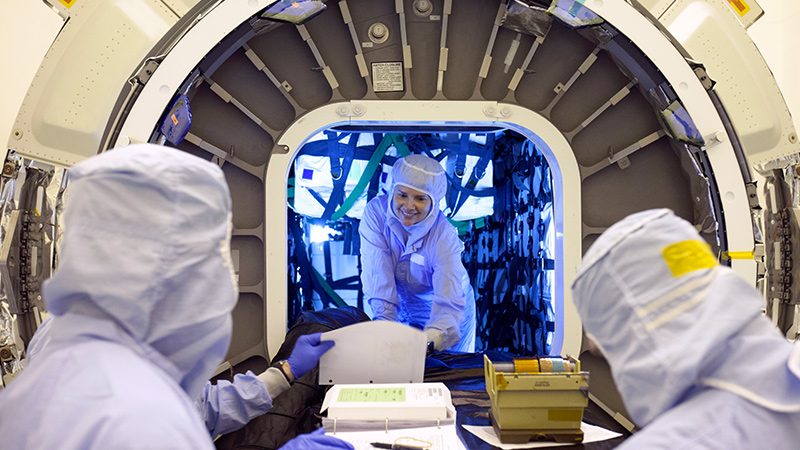

One thing NASA will do is “build off” its experience with the International Space Station and the commercial crew and cargo programs in which NASA is paying companies to deliver supplies and eventually crew members to the space station. (In the photo at top, workers prepare cargo to be loaded in the Orbital ATK Cygnus pressurized cargo spacecraft in March for a resupply mission to the International Space Station.)

After Lightfoot’s address, a panel of agency officials discussed the technological obstacles to meeting the timeline suggested in the NASA Transition Authorization Act of 2017. That law instructs NASA to study “a Mars human space flight mission to be launched in 2033.”

NASA calculates that it will need to work with partners to develop or enhance 38 technologies, but “not all of them are show-stoppers,” said Steve Jurczyk, NASA’s associate administrator for space technology during the panel discussion with other associate administrators.

Among the challenges are life support, precision landing and radiation shielding for astronauts. “Lots of the surface systems are going to be challenging,” Jurczyk said. “We don’t think solar power is going to be viable on the surface, so we are developing 10-kilowatt nuclear reactors to power the systems for crew as well as the systems for in situ resource utilization, producing fuel, oxygen, etc.”

Regarding transportation, balancing weight and fuel will make it difficult for craft to enter and exit the Martian atmosphere, Jurczyk cautioned. When asked by the panel moderator if NASA would “rely on companies like SpaceX,” he agreed that commercial companies should play an important role in delivering cargo.

How broad might Mars cooperation extend geographically? NASA since 2011 has been barred by federal budget rules from directly coordinating with perhaps the biggest emerging player in space exploration: China. Beijing aims to land a robot on the moon by 2018 and in 2020 launch a probe to orbit and land on Mars. In April, China launched a cargo ship to dock with its Tiangong-2 space lab in low Earth orbit as a step toward its goal of assembling a larger space station.

NASA’s Bill Gerstenmaier, associate administrator for human exploration and operations, was asked about a possible role for China. He cited the congressional ban on NASA working directly with the China National Space Administration, but added that China’s projects are “exciting” and said “we will figure out a way to work within the constraints we are given.”

Gerstenmaier noted that China is a member of the same major multinational space groups that discuss science and exploration goals, and he suggested that this would provide a route for sharing appropriate scientific data. NASA can also avoid political hurdles while keeping China in the loop on space exploration by publishing voluntary standards for space hardware, including docking between spacecraft, Gerstenmaier said.

“We are going to set other standards in terms of life support systems, pressure levels in terms of modules, standards on bus architecture, power systems, etc.,” he said. “If people build to those standards then all of a sudden we have intercompatibility; we can move components from one country to another country into our architecture.“

"We don’t think solar power is going to be viable on the surface, so we are developing 10-kilowatt nuclear reactors to power the systems for crew as well as the systems for in situ resource utilization, producing fuel, oxygen, etc.”

Steve Jurczyk, NASA’s associate administrator for space technology