Inside NASA’s long handoff of orbital research to private sector

By Cat Hofacker|October 25, 2023

No. 2 official describes budget and timing challenges

AIAA ASCEND, Las Vegas — NASA’s Pam Melroy talks about the International Space Station with the air of someone musing about an old family farm that once fed everyone but will need to be razed soon to make way for the new.

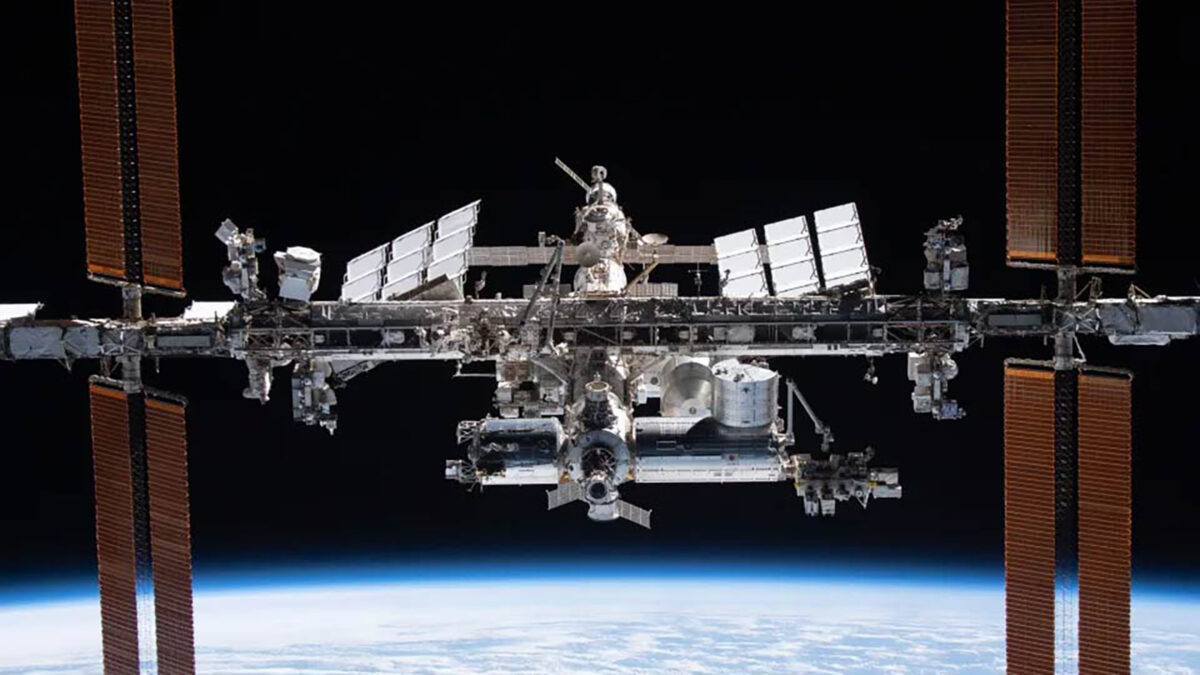

NASA is “still proud” of what it’s achieved with the multibillion-dollar orbiting lab, the agency’s deputy administrator said when I interviewed her Tuesday on the sidelines of AIAA’s space conference. “We definitely built something magnificent and amazing and very powerful and capable, but it is a huge station now causing us problems,” she said, referring to the cost of maintaining the station and the need to free up resources for other priorities, such as the Artemis lunar landings.

NASA wants to shut down the aging station with its partners and deorbit it in 2030 to avoid disrupting the companies that plan to establish privately run space stations. It also wants to make that shift without jeopardizing the continuous human presence in low-Earth orbit since 2000, when the first habitable module of ISS was launched. The Biden administration has committed to funding the U.S. segment through 2030, and plans call for a yet-to-be-built deorbit module to be sent to the station by 2031 to drag the entire station down into the atmosphere on a course to crash into the Pacific Ocean. That is, if Russia doesn’t separate its portion of the station first, as it threatened to do last year. Roscosmos said in an April statement that Russia would fund its portion of the station through 2028, but has not clarified its deorbiting plan.

NASA in September issued a request for proposals for the deorbit module and plans to award a contract in April. Melroy estimates that development will take “five, six years” — assuming the funds are there.

If the U.S. Congress doesn’t appropriate “enough money for a deorbit vehicle, we can’t deorbit ISS until we know we can do it safely,” she says. “The problem with extending [operations] is that’s very hard for our commercial LEO destinations because their business model revolves around when NASA needs their services.”

As a bridge for commercial developers, NASA earlier this year released draft requirements describing the rules for hosting NASA-funded experiments and astronauts on privately owned stations. The agency has also urged developers to seek out other prospective customers, such as other countries that might want to send their astronauts, and private companies that want to conduct on-orbit research and experiments.

None of which is to say that NASA doesn’t plan to continue supporting developers financially and with access to ISS. Melroy points to the mix of government-sponsored researchers and private citizens who spent time on ISS in two missions arranged by Axiom Space, the Houston-based space company. Axiom also has a unique agreement with NASA that will permit the company to attach three modules to ISS, the first being Hab One in 2026, as a precursor to detaching and rejoining them to create Axiom Station, the company’s planned free-flying lab. The first customers are to be hosted in the years before ISS is deorbited.

Axiom Station is one of three such commercial projects that have received NASA funding. Blue Origin of Washington and its partner, Sierra Space in Colorado, plan to erect Orbital Reef, whose design NASA is helping fund via a 2021 contract. To prove the concept of operations, Sierra plans to conduct a space demonstration of the station’s proposed inflatable module technology in 2027. A crew of four Sierra astronauts would live aboard this habitat module for up to a month to test operations. Meanwhile, Voyager Space Holdings of Colorado and its partners have received funds from NASA to help draw up plans for their Starlab station, with plans calling for the initial module to be launched in 2028.

That’s the future, but for now, NASA is cherishing its old farm, ISS. Melroy pledges to “really maximize the use of” the station throughout its remaining years.

“The last flight of the shuttle was like a gut punch in a lot of ways,” says Melroy, who flew three shuttle missions to ISS. “And yet, I have seen that [retiring the shuttles] created the open space for innovation, for improvements in safety, for new technologies, for higher levels of autonomy that enabled more people to go to space.” So if “every program comes to an end,” the biggest question is “what do you want that end to be?”

For ISS, the first decade was about completing assembly of the station, which was accomplished in 2011. The second revolved around “learning how to live for long periods of time in space and how to efficiently use crew and do science.”

“This third decade is what’s going to really unfold all of the opportunities” for on-orbit research, she says. “I love the idea that we are fully utilizing the station and that its last decade will be about bringing that vision to its full potential.”