Stay Up to Date

Submit your email address to receive the latest industry and Aerospace America news.

With taxpayer dollars, their own reserves and some nudging from Congress, airlines in the U.S. are planning an ambitious comeback for when the coronavirus pandemic subsides and travelers begin looking to the skies again. Cat Hofacker explains.

Under the Arizona sun, hundreds of aircraft sit in orderly rows, awaiting their return to the sky. Until coronavirus travel restrictions and social distancing guidelines are lifted, the only visitors these planes will see are the mechanics who stop by weekly or monthly to check tire pressures and change out the mylar coverings shielding the aircraft from sun and dust.

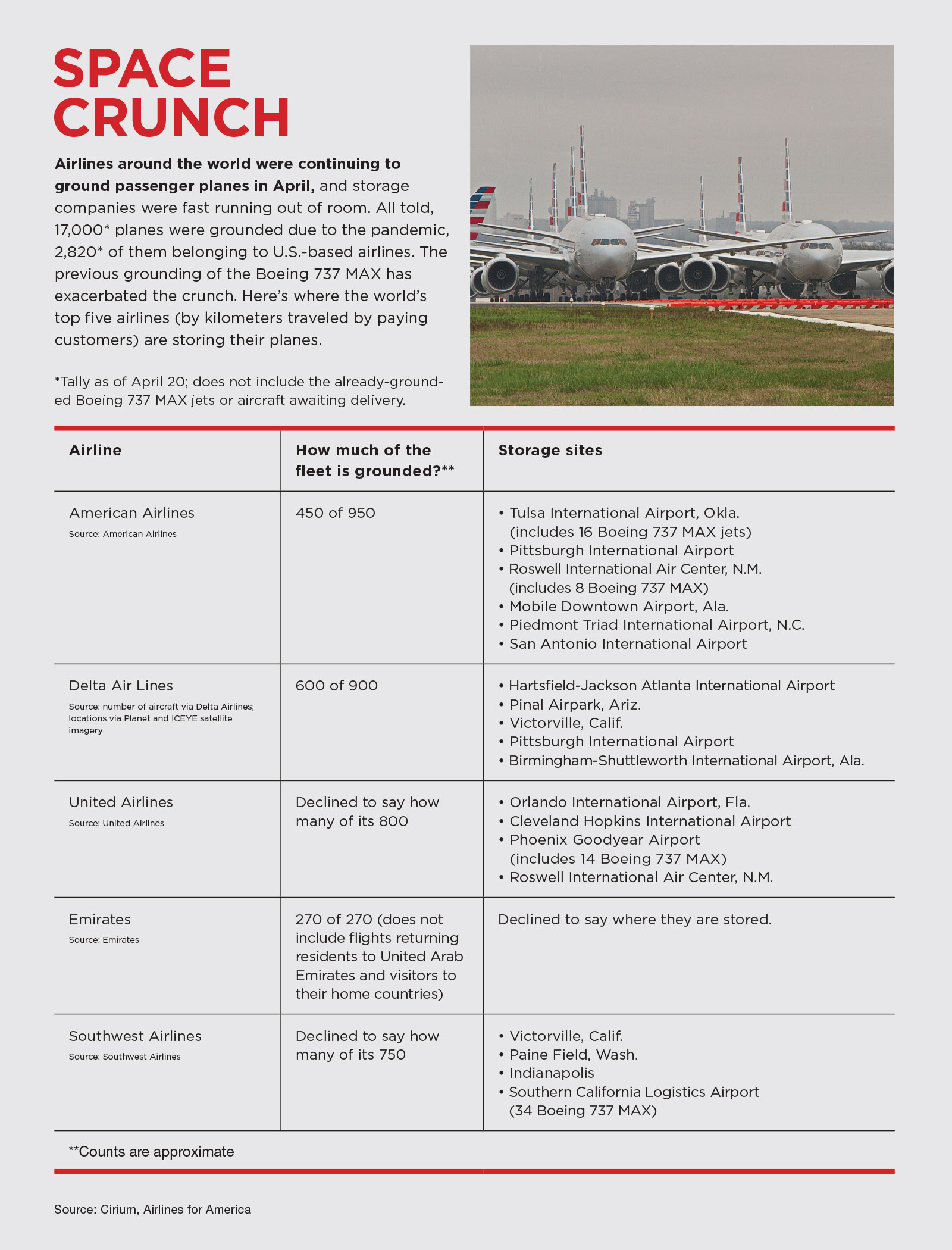

As I write this in mid-April, 2,820 passenger aircraft were confined to open lots like this one and empty taxiways at U.S. airports, a figure that amounts to 46% of the planes flown by domestic airlines, according to a count taken by the lobbying group Airlines for America.

In happier times, those aircraft would be part of an industry that directly and indirectly generates nearly 4% of the U.S. gross domestic product. Getting back in the air is not just about getting travelers from here to there; having so much of the fleet grounded has begun reverberating through the supply chain, including among aviation research and development projects.

Thousands of planes are idle, but the leaders of the air transport industry and U.S. lawmakers are anything but. Steps are being taken on the financial, workforce and technical fronts to position airlines for their best shot at surviving the expected long slog back as the coronavirus recedes and travelers begin thinking about flying again.

At this writing, June could mark the downward turn in daily deaths across the U.S., according to the University of Washington model shown at the televised White House briefings. But, from listening to pandemic experts, I know that more cycles could lie ahead and that when you read this in May, the projections could look better or worse because they depend on human behavior.

Once state governors lift their stay-at-home orders or other restrictions, the question becomes how fast consumers will return to the air.

“The flying public isn’t just going to go run into a crowded airport and jump on a crowded plane right away,” predicts Brian Foley, founder of the aerospace consultancy Brian Foley Associates in New Jersey. “It’s going to have to be a relearned behavior where it’s OK after being told to hide in your house for weeks on end.”

The following account is based on interviews with analysts, a legislator and technical experts, and reviews of video presentations, letters and memos released by airline executives. American Airlines, Delta Air Lines, Emirates, Southwest Airlines and United Airlines — the top carriers in terms of kilometers traveled by paying passengers in 2018 — each declined to make executives available for interviews, telling me that the situation is just too fluid to comment.

Parking passenger planes

The growing volume of planes in storage, and the length of time they may need to be stored, is unprecedented. The good news is that even before the virus, a handful of maintenance, repair and overhaul companies had honed a specialty in storing passenger jets in such a way as to avoid exterior corrosion, sun damage and the caustic effects of fuels. One of them is Ascent Aviation Services, based at Pinal Airpark near Tucson, Arizona. In normal circumstances, Ascent would host perhaps a few dozen aircraft awaiting maintenance or retirement, when valuable parts must be kept ready for stripping. As I write this, there are 240 aircraft on Ascent’s 500-acre lot, which is headed toward full capacity of 400 planes probably by mid-June.

“We’re adding aircraft every day pretty much,” says Scott Butler, chief commercial officer of Ascent.

At Pinal, some planes linger in active parking, where mechanics keep aircraft “a day away from flight readiness” by firing up the engines and rotating the tires regularly, Butler says. Other aircraft sit in short-term or long-term storage, where mechanics disconnect and preserve engines and other major systems so planes can linger for months or, if necessary, for years with little upkeep. Flight manuals supplied by Airbus, Boeing and other manufacturers define the specific steps mechanics must take.

The low humidity in Arizona guards against external corrosion compared to, for instance, Pittsburgh International Airport, where American Airlines has parked some planes. There is a tradeoff, though, for the dryness of Arizona. The accompanying high temperatures would wreak havoc on computers and electronics, so Ascent mechanics stretch sheets of mylar across all windows, sensors, engines and external ports to reflect sunlight and keep out dust. Tires and other rubber parts are likewise covered.

“Anything you would think that’s moving or going to move has to be greased, and anything that’s sitting, you want to make sure it’s protected as well as it can be,” Butler explains.

For active parking, mechanics must visit aircraft weekly, rotating tires to prevent flat spots and powering up engines to vaporize any moisture that might have collected. That’s unnecessary for short-term and long-term storage, because the engines and fuel lines must be drained and then filled with a non-caustic preservation oil. From there, mechanics visit these planes monthly to check tire pressure, recirculate the oil inside the engines, and open cockpit and cabin doors to circulate air and cool the interior.

Aircraft at Pinal or elsewhere can linger in short-term storage for up to a year, a comfortable margin given the uncertainty about when coronavirus-related travel restrictions will end. But some planes moved to storage because of the virus will never fly again. American Airlines said in March it would retire its remaining Boeing 767s by mid-May, ahead of the original 2021 end-of-service date, as well as its Boeing 757 fleet in 2021 instead of in 2025.

For those planes and others that will sit idle for longer than a year, mechanics take additional steps to “pickle or preserve the major systems,” Butler says. That includes disconnecting electronics and removing batteries. These planes also receive monthly inspections, along with more in-depth checkups about four times a year.

It’s a process playing out at numerous locations around the world, and analysts and storage companies are unsure whether there will be enough room. As of mid-April, airlines worldwide had grounded about 17,000 aircraft, which amounts to two-thirds of the global fleet, according to Cirium, the London-based aviation data and news service. Compounding the space crunch are the hundreds of Boeing 737 MAX, grounded since March 2019 after the two deadly crashes that killed 346 people. About 70 MAX jets from the American, United and Southwest fleets are parked at various U.S. airports awaiting recertification by FAA, and Boeing is storing about 400 new planes in Washington and Texas, pending delivery to dozens of airlines.

Betting on bailouts

Storing a plane is vastly cheaper than flying one with a handful of passengers, but the fee of $2,000 to $5,000 per month, depending on the aircraft size, adds up quickly. Plus, airlines in the U.S. continue to fly some routes under the terms of the U.S. coronavirus bailout, which means they must pay for the people and apparatus surrounding that. Those are steep costs to ferry what Airlines for America says is an average of 10 passengers per flight.

For the airlines, maintaining cash flow has become the highest short-term priority.

“If we don’t have cash, we stop operating and nobody has any opportunity to come back and fight another day,” Southwest Airlines CEO Gary Kelly told employees in an April Q&A, according to a video.

The Geneva-based International Air Transport Association estimates that the global air transport industry is on track to lose $314 billion in revenue this year, a loss that would equal 55% of the total revenue in 2019. Airlines are reacting by cutting flights, deferring maintenance when safety permits and encouraging employees to take voluntary leaves of absence. But these cost-cutting measures can’t go too far, lest airlines undermine the very processes and workforce they’ll need once the virus subsides and demand returns.

To help the passenger airlines get ready, the U.S. in March created a $50 billion cash-flow bridge for them (plus $8 billion for cargo carriers), but it is not easy money. Creating this portion of the $2.2 trillion Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security, or CARES Act, was colored by long memories of airline actions in the aftermath of the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks.

After the attacks, it took three years for passenger numbers to completely recover, according to the Bureau of Transportation Statistics. In the meantime, United Airlines accepted $774 million in grant money and then declared bankruptcy in December 2002. U.S. Airways accepted $331 million and declared bankruptcy in August 2002. American Airlines did not declare bankruptcy but laid off tens of thousands of workers after receiving $694 million in grant money.

The bankruptcies were “egregious,” Rep. Peter DeFazio, D-Ore., who was in Congress at that time, told me in an April interview. “They got assistance, and then when they burned through the assistance, the airlines declared bankruptcy, took away their workers’ pensions, busted the unions,” he said. “So I said, ‘not going to happen that way this time.’”

So for the CARES Act, DeFazio and House Democrats insisted that $25 billion of the airline funds be doled out in grants specifically to pay the salaries and benefits of pilots, flight attendants and other workers. Airlines are also prohibited from laying off workers until October. The other $25 billion is loans that airlines can spend on storing or maintaining their planes. These U.S. taxpayer dollars must be paid back to the Treasury Department with interest; expressly forbidden are stock buybacks to buoy value, dividends and executive bonuses.

The reactions to such strings have been mixed among airline executives and analysts. In one view, they amount to tough love to ensure that the airlines have the tools to get enough aircraft back in the air.

Analyst Foley says the conditions of the aid are not ideal, “but there is really no other choice” if the airlines are to avoid bankruptcy and be ready to fly once travel demand increases. “We need a national air system and having these airplanes on the ground for any length of time won’t serve anyone’s interest.”

Aviation consultant Mike Boyd of Boyd Group International in Colorado says the government’s conditions get to “the need to have the airlines alive and ready to go” once the pandemic passes while also ensuring taxpayer money isn’t wasted.

American Airlines CEO Doug Parker greeted customers and employees with a smile hours after President Donald Trump signed the CARES Act: “The question I keep hearing from our team is, ‘are we going to be OK?’” he said in a video message. “I’m happy to report the answer to that question is yes.”

Delta Air Lines CEO Ed Bastian was less enthusiastic in an April memo issued a week after the bill’s passage, writing that Delta’s portion of the payroll grants “are not nearly enough” to cover costs.

Nevertheless, Delta and nine other airlines — including American, Southwest and United — agreed on terms with the Treasury Department three weeks after the CARES Act passed. Airlines receiving more than $100 million in payroll assistance must now pay back 30% of the money, no longer purely grants, and offer the U.S. government shares at a reduced price.

As of April, the Treasury Department was still negotiating with airlines on the terms of the $25 billion in loans, but ownership shares are on the table in exchange for those as well.

The $25 billion payroll assistance frees up much-needed cash for other expenses, Foley says. It also helps with a speedy return to service by eliminating the time it would take to retrain and rehire workers. However, the grants run out after Sept. 30, following which nothing would prevent airlines from laying off pilots, flight attendants and technicians if money is still tight.

“I’m not convinced by Sept. 30 we’ll be back to where we were as far as previous staffing levels,” Foley says.

United is one of the airlines already thinking along those lines. In a memo sent out the day the CARES Act passed, President Scott Kirby and CEO Oscar Muntz wrote that despite the aid, future layoffs are a possibility if travel demand remains “suppressed for months” as expected.

“If the recovery is as slow as we fear, it means our airline and our workforce will have to be smaller than it is today,” the memo reads.

JetBlue Airways CEO Robin Hayes, in a letter to employees, voiced another concern after the payroll assistance was finalized: The cash that’s buying “some breathing room” today means more debt to contend with tomorrow. “Thankfully, we entered this crisis with one of the stronger balance sheets in the industry,” Hayes wrote, “but we will come out of this with significant debt to pay down.”

Adjusting to the new normal

Airlines could be facing two to three years before air travel approaches the record-setting year of 2019, said John Grant, senior analyst at aviation data firm OAG, in an April webinar on the impact of the coronavirus. In 2019, according to the Bureau of Transportation Statistics, 1 billion passengers flew to, from or within the U.S., which was an “all-time high.”

As to when airlines will start adding flights back into their schedules, Grant said, “it is unlikely that we are going to see anything like a recovery back to January 2020-type capacity before this time next year at the earliest.”

Foley says the next likely development will be decisions by airlines to defer deliveries of new aircraft “just to try to preserve some capital.” He expects airlines to slowly bring their existing aircraft out of storage as travel demand increases, but that has its own challenges. The longer an aircraft has been grounded, the longer it takes mechanics at storage facilities like Ascent Aviation Services to restore it to flight readiness.

“If it’s coming from a short-term or an active parking, it’s not as tedious because you haven’t taken as many things offline,” Butler of Ascent says, but lingering social distancing guidelines could play a role here as well.

A team of 10 mechanics would usually spend about a week bringing a wide-body aircraft out of storage: removing the mylar coverings, draining the preservation oil and refueling the tanks, reconnecting the electrical systems and so on. This process could stretch on if mechanics have to stay 2 meters apart, especially if the aircraft requires more extensive maintenance to get it ready to fly again.

And once planes do return to flight, what might air travel post-coronavirus look like? Steps taken during the pandemic offer some clues. Through May, Delta Air Lines will leave the middle seat of each row open and have passengers board 10 at a time to prevent crowding. Emirates in the United Arab Emirates tested passengers before they boarded an April flight to Tunisia for the virus via a blood test that shows results within 10 minutes.

Similar measures are likely to continue as travel demand picks back up, predicts analyst Boyd. While he’s skeptical that leaving the middle seat open is an effective way of separating passengers, blood tests are something “that can be done very quickly and will have to be done.”

But even when demand for air travel does pick up, restoring profits will take priority over propulsion and other technological advancements, predicts Richard Aboulafia, analyst with the Teal Group of Virginia.

He expects the first to go will be engineering and design budgets for “advanced new product development” such as hybrid-electric aircraft and sustainable aviation fuels. “You can safely add three to five years for just about anything that’s in the pipeline,” he says, more if recovery is slow.

Foley says that also goes for future purchases of in-development aircraft like the Airbus A321XLR, scheduled to debut in 2024 with 30% less fuel burn per seat compared to the Boeing 757. If travel demand does not reach 2019 levels until the mid-2020s, airlines could be relying on their older, less-fuel efficient aircraft for years to come. Manufacturers are adjusting accordingly; Airbus said in April it will cut production of wide-body aircraft by 40%, making only six A350s and two A330s per month.

It’s a bleak state of affairs, but OAG’s Grant sees a small ray of sunshine. In the April webinar, he pointed to Chinese airlines, which since early March have begun adding back millions of seats on flights within the country to their schedules, according to OAG data.

Foley says a longer view of history also shows reason for optimism. The scale of the impact from the coronavirus pandemic exceeds anything the industry has experienced before, but the airlines have so far survived every tragedy they’ve encountered.

“People said after 9/11, ‘the industry will never be the same; it’ll never recover,’ and it certainly did,” he says. “This industry will recover again.”

About cat hofacker

Cat helps guide our coverage and keeps production of the print magazine on schedule. She became associate editor in 2021 after two years as our staff reporter. Cat joined us in 2019 after covering the 2018 congressional midterm elections as an intern for USA Today.

Related Posts

Stay Up to Date

Submit your email address to receive the latest industry and Aerospace America news.