Stay Up to Date

Submit your email address to receive the latest industry and Aerospace America news.

Test Monday could prove survival of crew in case of launch failure

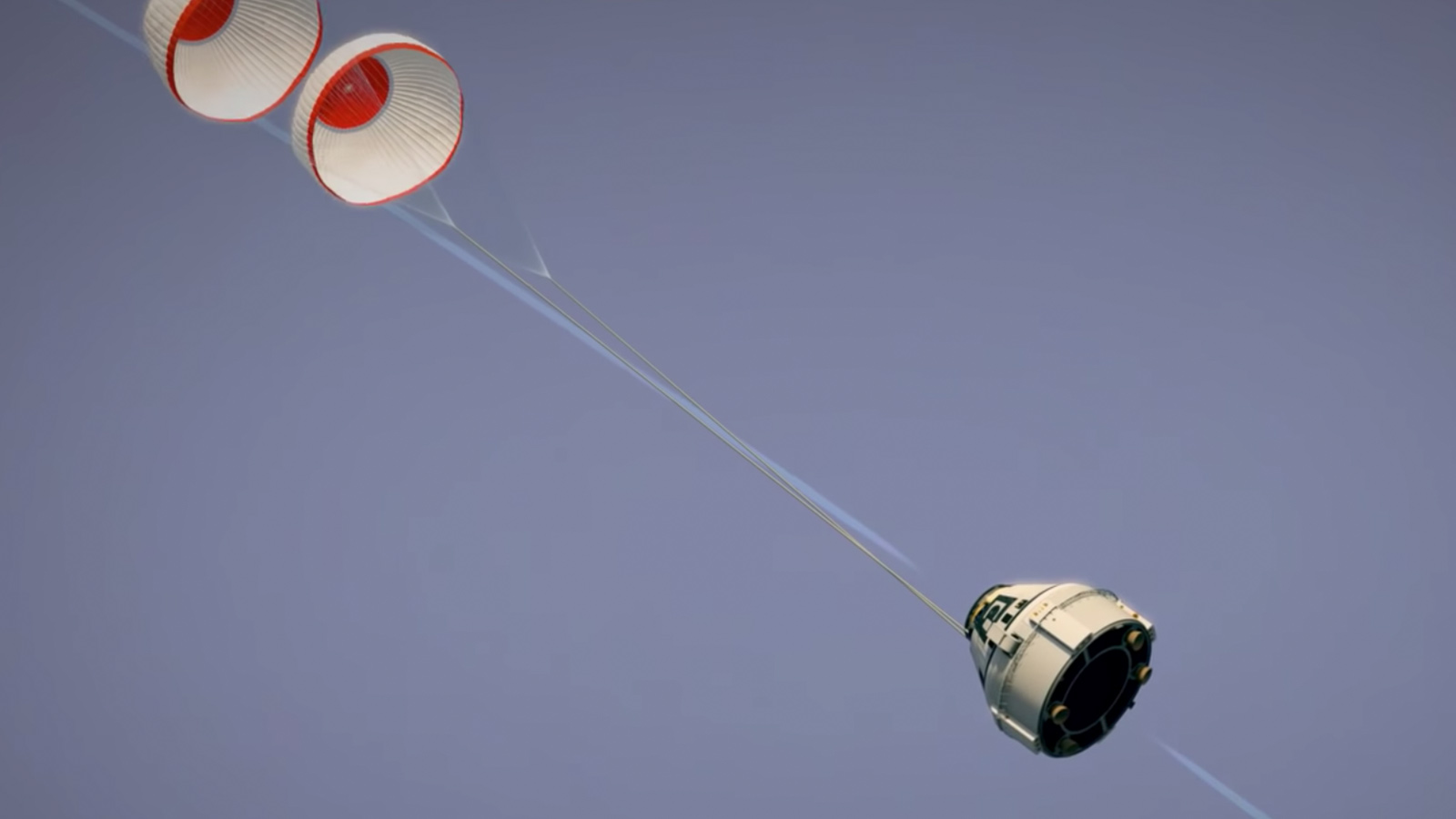

UPDATE: The Starliner pad abort test concluded about 9:17 a.m. EDT Monday. All appeared to go as planned, except for the fact that one of the capsule’s three main parachutes didn’t deploy. “The initial indication is that we’ve had a successful pad abort test,” says a Boeing spokeswoman.

Boeing will face a moment of truth Monday in the New Mexico desert, where a CST-100 Starliner crew capsule sits atop a stumpy rocket called a service module.

Someday, hopefully in 2020, a capsule like this one will blast as many as seven astronauts to the International Space Station, but for now, a test dummy will have to do.

Plans call for a collection of engines and thrusters to boost the Starliner off the pad, as if there were a crew inside who needed to be saved from an exploding or fizzling launch vehicle. The test dummy and capsule should fall back to Earth softly under parachutes, with its sensors recording survivable G forces.

Until this launch abort system is proven, Starliner can’t do its part to help end U.S. reliance on the Russian Soyuz spacecraft that have been NASA’s sole method of transportation to the ISS since 2011.

“A lot of everything that we’ve been working on for the last eight years or so [is] all wrapped up in about a 90-second test, so it’ll be pretty exciting,” said Chris Ferguson, head of Starliner crew and mission systems, during the International Astronautical Congress last month in Washington, D.C.

NASA estimates that its Commercial Crew contractors Boeing and SpaceX will begin crewed flights in the “first half” of 2020, more than two years after the original 2017 deadline.

“It’s a very complicated dance as we’re getting ready to go fly,” said Commercial Crew Manager Kathy Lueders this week during a presentation to the NASA Advisory Council’s Human Exploration and Operations committee, according to a webcast.

Here’s how things are supposed to go Monday for the pad abort test, or PAT:

Boeing flight controllers at White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico will fire the four launch abort engines, or LAEs, and 12 smaller orbital maneuvering and altitude control, or OMAC, thrusters in the base of the service module to propel the capsule off the pad. The LAEs will fire for about five seconds, producing a combined 72,500 kilograms of thrust. The OMAC thrusters will then pulse to flip the capsule tail first as it continues its ascent.

Once Starliner reaches an altitude of about 1.5 kilometers, a sequence of parachute deployments begins. At this point, the service module is still attached. Two drogue chutes slow the descent, and then three pilot chutes unfurl to continue slowing the fall while also pulling out the three main parachutes. About 34 seconds into the test, the service module and heat shield jettison, leaving the capsule to decelerate under the chutes. Close to the ground, airbags inflate under the capsule to cushion its landing, about 1.5 km north of the launch site.

Boeing does not plan to reuse this particular Starliner capsule, one of three the company is building to complete the necessary tests before it starts regularly flying astronauts to the space station. Along with the test dummy, the entire capsule will be “heavily instrumented” with sensors, said Boeing spokesman Josh Barrett.

“Some of the telemetry will be transmitted back [to the grounds crew] during the test” as well, Barrett said.

NASA will broadcast Monday’s test on NASA TV and its website. The three-hour launch window opens at 9 a.m. Eastern time, with coverage set to begin at 8:50 a.m.

Pending success, Starliner’s first uncrewed flight is scheduled for Dec. 17, when it will launch from Space Launch Complex 41 in Florida atop a United Launch Alliance Atlas V rocket and dock with the ISS.

Meanwhile, SpaceX plans to prove its ability to whisk a crew to safety by launching an empty Crew Dragon capsule atop a Falcon 9 rocket as though it were headed to the space station. After about 90 seconds, the SuperDraco thrusters on the sides of the capsule must propel Crew Dragon away from the rocket for a soft parachute descent into the Atlantic Ocean. That test is scheduled for early December from NASA’s Kennedy Space Center, Florida.

About cat hofacker

Cat helps guide our coverage and keeps production of the print magazine on schedule. She became associate editor in 2021 after two years as our staff reporter. Cat joined us in 2019 after covering the 2018 congressional midterm elections as an intern for USA Today.

Related Posts

Stay Up to Date

Submit your email address to receive the latest industry and Aerospace America news.