Women reflect on Apollo

By Debra Werner|July/August 2019

There was only one woman in Mission Control when Apollo 11’s lunar module landed on the moon; today women make up 34% of NASA’s workforce. Debra Werner talked to one of the pioneers.

When Neil Armstrong first stepped onto the moon, Frances “Poppy” Northcutt wasn’t at her desk at NASA’s Manned Spaceflight Center, now Johnson Space Center. She was resting up for her job the next day: helping guide the astronauts home.

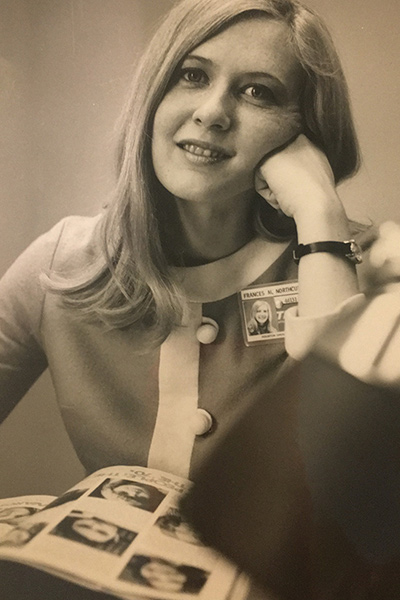

As the only woman on the Mission Control technical staff to that date, Northcutt was highly visible not simply for her blonde hair and fashionable miniskirts. Most of the women working for NASA or its contractors during the Apollo 11 mission typed letters, sewed spacesuits or assisted the overwhelmingly male engineering staff with calculations and reports.

“There were some extraordinary women who stood out,” says William Barry, NASA chief historian. “But for the most part the roles women played at NASA and in many government agencies at the time were secretarial and those sorts of jobs.”

Fifty years later, NASA is poised to begin sending astronauts to the International Space Station in commercial crew taxis. This time female engineers, while still in the minority, will share far more of the credit.

At Boeing’s Space and Launch Division, chief engineer Michelle Parker oversees the engineering team building CST-100 Starliner, the crew capsule scheduled for an October flight debut. Aerospace engineer Melanie Weber leads Starliner’s launch-pad team, and Starliner’s crew and cargo accommodations subsystem. Weber appreciates the mix of men and women working on Starliner after college courses in which she was sometimes the only woman in a class of 200. “Being female and Hispanic isolated me even more,” she says.

SpaceX, NASA’s other Commercial Crew contractor, did not make anyone available for interviews, but Gwynne Shotwell, the company’s president and chief operating officer and a mechanical engineer by training was recognized by Women in Aerospace with its outstanding achievement award in 2012 for her “extraordinary technical and business sense with a charisma and passion for space, education and advancement of sciences.”

Jessica Jensen directs mission management for the Dragon vehicles, including the cargo and crew versions. Crew Dragon could fly for the first time with crew by the end of this year.

Women still make up only 34% of NASA’s 17,373-person civil servant workforce and 28.4 percent of space agency employees are not white, according to NASA’s Workforce Strategy Division and Office of Diversity and Equal Opportunity. But that’s a dramatic change from the late 1960s, when women comprised about 17% of a staff of 218,000, Barry said. NASA began tracking minority employment in 1970 when 4.7% of civil servants were not white.

As the only woman in Mission Control, Northcutt attracted the attention of fellow engineers and media coverage. She was featured in Life magazine and Paris Match, the French weekly magazine. “I always felt that as a woman, I needed to prove myself more because people were watching,” she says. “I also felt the media coverage was an opportunity to get a message out to other women and to girls that women could do these jobs.”

A graduate of the University of Texas with a bachelor’s degree in mathematics, Northcutt took a job with NASA contractor TRW Systems Group in 1965 as a computress, a title like “computer” given to women who performed complex calculations. By the time Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin and Michael Collins traveled to the moon in July 1969, TRW had promoted Northcutt to an engineering role. Beginning with Apollo 8, she led a trans-Earth injection team, plotting the command module’s optimal trajectory on its return trip, tracking its progress in flight and revising the engine firing schedule if necessary to ensure the spacecraft would enter Earth orbit at the proper angle to splash down within range of U.S. Navy recovery ships.

Northcutt was still working for TRW in the early 1970s as she became increasingly involved in the women’s rights movement, inspired primarily by demands for equal pay, and in 1978 when she attended night school at the University of Houston Law Center. After graduating in 1981, Northcutt worked in the district attorney’s office prosecuting domestic violence before becoming a criminal defense attorney.

“I’m semiretired at this point,” Northcutt says, “but I still do a lot of work for women’s rights. My experience in the space program illuminated that for me.”

IN THEIR WORDS

Elaine Denniston

Keypunch operator for Apollo Guidance System Data at the MIT Instrumentation Lab (now Draper)

I punched the cards that eventually were turned into the program for the guidance system for the Apollo project. Punching cards is punching cards whether you’re in an insurance company or working on the Apollo project. The programmers would give me 11-inch by 17-inch sheets of paper. They would write the program in blocks. My job was to keypunch it onto the cards. Remember, direct access to computers didn’t happen back then. After I’d been doing it for a while, I could spot a missing symbol and say, “Should you have that?” They would say, “Yeah. Thanks.” I was known for that and for telling them to get their programs in on time.

Mary Gene Dick

Secretary to the deputy director Mississippi Test Operation

now Stennis Space Center)

I did whatever needed to be done: type something up, run a letter, make travel arrangements, take somebody to the airport. We were on a mission to do the biggest exploration mankind had ever done, and it was thrilling. My husband and I were invited to the launch at Cape Canaveral. When we saw it was a good launch, I cried, I sang. I wanted to wave my American flag and sing “God Bless America.” We were on our way to the moon.

Frances “Poppy” Northcutt

Apollo 11 engineer

You can’t communicate directly with the spacecraft when they are doing their maneuver, and you don’t have any tracking because it’s on the backside of the moon. You don’t know whether the maneuver went well or didn’t go well. You lose signal for about 30 minutes. Bad things can happen if they overburn or underburn or the burn doesn’t start on time. When they come around, it takes a few minutes for folks to tell you where the spacecraft is. Is it where it’s supposed to be? If it’s not, you might have to act quickly to get the information up there to correct their trajectory. Their onboard computer didn’t have nearly enough capacity to compute trajectories.

Saydean Zeldin

Apollo software engineer, MIT Instrumentation Lab (now Draper)

I started as an engineer working on Apollo guidance. The astronauts knew it as P40 [software] because that’s what they would key in when they wanted to burn an engine. I had to figure out the change in trajectory, when to burn an engine and how long it should burn. I did the programming for the Apollo computer and for the simulator, which used a very sophisticated compiler that could use matrix and vector equations. Every time you would key in a matrix times a vector, you had to use three punch cards: one for the exponent, one for the mainline and one for the postscript. I had three daughters. I would work all day, come home late in the afternoon, let the babysitter go, have dinner and go back to the lab.