Preventing space pollution

By Debra Werner|April 2018

Experts affiliated with U.N. are pushing to establish best practices

Those who are in the business of launching rockets and operating satellites could soon have a set of internationally approved guidelines that are meant to put everyone on the same page about how to be good stewards of the orbital environment. Twenty-one guidelines are scheduled to be assessed in June by the United Nations Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space, which is expected to pass them to the General Assembly for consideration. The nine newest were approved in February in Austria by a COPUOS working group that included members from China, Europe, Iran, Russia and the U.S. These guidelines join 12 that were approved in 2016 but never passed forward. The working group was formed in 2010, the year after an Iridium communications satellite and a defunct Russian military satellite collided, and three years after China destroyed one of its satellites in an anti-satellite missile demonstration that left thousands of pieces of debris in orbit.

Canadian David Kendall has chaired COPUOS, the United Nations Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space, since 2016. He led science and technology programs in the Canadian Space Agency for eight years:

“These 21 new guidelines are nonbinding and voluntary. This reflects the reality under which COPUOS operates. Many states believe that obtaining agreement on binding treaties is not possible in the near future given geopolitical differences, although there remains the hope that binding instruments on essential issues might be possible after further negotiation and discussion. The process now is to encourage all states and international intergovernmental organizations to take measures to ensure that the guidelines are implemented to the greatest extent feasible and practicable in accordance with their respective needs, conditions and capabilities and with their existing obligations under applicable international law. While one could consider that to be fairly soft, it does have a moral suasion. States that have signed onto these guidelines have an obligation to follow through.

“Most people do not understand the complexity of trying to reach agreement at this level of detail. Every word, every dot, every comma was negotiated to ensure consensus. There were times when we threw up our hands and thought, ‘This isn’t going to work.’ But in the end, it did. We have a committee whose members are working in spite of political differences to ensure the security, safety and sustainability of outer space, to ensure that this global commons is available now and in the future because, if we screw it up, we are in big trouble.”

South African Peter Martinez, a space policy expert chairs the United Nations Working Group on the Long-Term Sustainability of Outer Space Activities. He is director of SpaceLab, a graduate school within the Department of Electrical Engineering at the University of Cape Town. He is also a former chairman of South Africa’s Space Council:

“The fact that the world space community has been able to agree on any guidelines at all is a step forward. It was a process of getting everyone on the same page first on the importance of this issue and secondly on the kind of measures we should take to preserve the space environment for current and future generations. These discussions will not end here. This is the first step in what will be an ongoing discussion in COPUOS and in the global space community, including international professional and industry associations.

“This is new guidance that supplements the existing guidance in treaties, national laws, standards, etc. In well-established spacefaring nations, many of the practices in the guidelines are already accepted practices but they may be rather less well or not at all established in emerging space nations. The guidelines give some direction, particularly to emerging space actors, about responsible behaviors in outer space. We are very much hoping these voluntary non-binding guidelines will assist states that are developing their space capabilities and that even established actors will be informed by them in formulating their own space activities. The idea is to try and get everyone on the same page in terms of behaving in a responsible fashion in outer space and not contributing to the degradation of what is becoming an increasingly fragile environment particularly in low Earth orbits.”

American Victoria Samson analyzes military space and security issues in the Washington, D.C., office of the nonprofit Secure World Foundation, headquartered in Broomfield, Colorado:

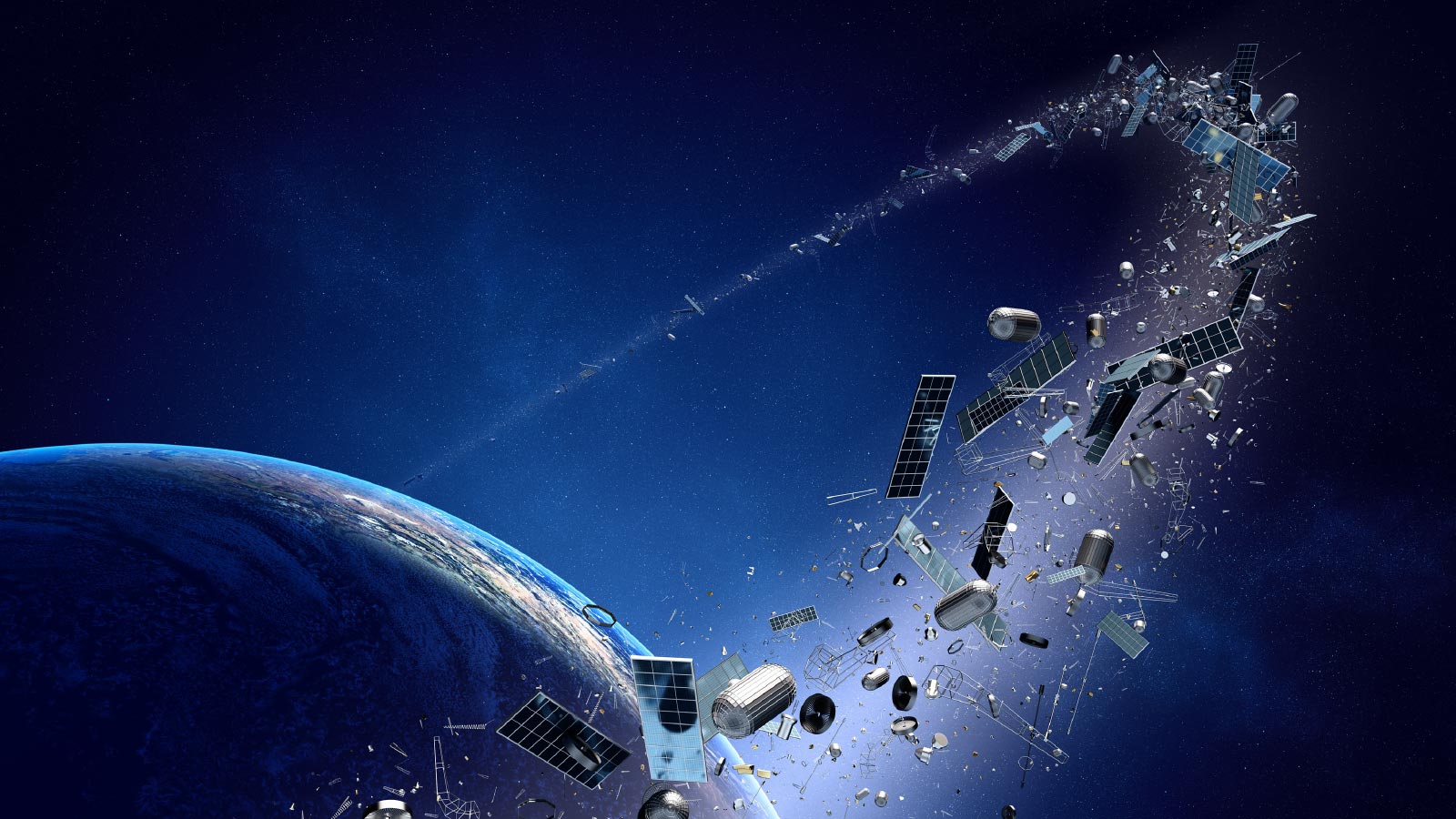

“Now there are over 60 countries with space capabilities or interests. The use of space is also changing. We are seeing mega-constellations and new activities proposed, like proximity operations and active debris removal. It’s good to have rules of the road to ensure that space is usable and sustainable over the long term. That’s helpful from an international perspective and also from a U.S. national security viewpoint. All you need is one person to do something either maliciously or, more likely, accidentally that leaves so much debris in an orbit it becomes financially unrealistic for anyone to use it.

“The COPUOS process, while lengthy, allows for multiple stakeholders to give input and to voice their concerns. That makes the guidelines stronger because they are coming from a broad base of background and experience. You have countries sitting together, the United States, Russia, China, Iran, Canada, Switzerland, with a variety of different interests and concerns. The fact they were able to come to agreement on 21 guidelines is a real win.”

American John Crassidis teaches space situational awareness at the University of Buffalo in New York, where he also directs the Center for Multisource Information Fusion. He is an AIAA fellow:

“The guidelines are good because they raise awareness. The United Nations is saying this debris problem is important. If some NASA office published the guidelines, they would not get the same exposure.

“Some of the guidelines are very pointed. One had to do with laser beams passing through outer space. That’s obviously a good one. You don’t want to dazzle a satellite by mistake. On other ones, I don’t see much cooperation. One guideline calls for countries to perform conjunction assessments during all phases of controlled flight. For a lot of satellites, we don’t know if they are going to do a maneuver because they don’t belong to us. Yes, it would be good for those countries to share the information on when they are going to do a maneuver but I don’t see countries providing that information. I don’t see why they’d want to.

“Guidelines to limit the amount of debris are good. Obviously, you don’t want to put more debris up there. If the Kessler Syndrome keeps going, low Earth orbit is going to essentially be useless to us. People should pay attention to this debris problem because it’s going to affect future generations.”

Jonathan McDowell, a British and American citizen, is an astrophysicist at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Massachusetts. His paper, “Critical Issues Related to Registration of Space Objects and Transparency of Space Activities,” appears in the February issue of Acta Astronautics, the journal of the International Academy of Astronautics:

“The current registration system established during the Cold War when there were only American and Soviet satellites is inadequate for 21st-century space traffic management when, for example, an Indian rocket launches 100 satellites from many different countries. A few percent of satellites are never registered. Most of those are not due to malign intent but due to bureaucratic screwups or turf wars.

“The bigger problem is a lack of transparency. That’s what the new guidelines try to address. What happens to the satellites after launch? Tell us when you are going to move your satellite so we don’t move at the same time and accidently hit you.

“The other thing the guidelines say is, ‘Get your act together before launch to decide who is the launching state’ [meaning the country responsible for registering the satellite with the U.N. Office for Outer Space Affairs.] A number of satellites are unregistered because the rocket owner’s host country thought the satellite owner’s host country should register it and the satellite owner never informed their host country.

“It’s good that the countries agreed on these policies but there is a lot more work to be done in terms of defining standards and getting people to start adopting them.”

Canadian Jessica West manages the Space Security Index, an annual risk assessment produced by experts from Australia, Canada, China and the U.S., under Project Ploughshares, a nongovernmental organization that encourages policies to prevent war:

“Mostly, the guidelines codify best practice, which is fine because they need to be adopted by everybody. They also strike a balance between expecting that everyone will adopt best practices and acknowledging not everyone has the same technical capabilities. I appreciate the attention it gives to cooperation and technical assistance because space is growing into an environment with a lot of different actors. As access continues to grow, it will be important to have everybody on the same page and applying the same standards.

“The guidelines also start to tackle some of the trickier sustainability questions on the horizon concerning small satellites. Do all satellites have to follow the same standards of safety and respect for the environment or do small satellites have a different set of obligations? This sets the stage for a similar set of obligations across all satellites and starts to point toward things that will make it easier to manage traffic in outer space and debris. It points to the fact that small satellites should have tracking sensors which would enable better space traffic management from the ground, particularly if we are starting to talk about these large constellations of satellites that are being planned.

“The guidelines are voluntary, but I wouldn’t write off the voluntary nature. Most states take their political commitments very seriously and don’t see much difference between binding and voluntary commitments. When you make an agreement and put your country’s name on something, that is a pretty powerful statement. And it sets an expectation that it will be implemented. Voluntary guidelines also can be updated more easily, which is an upside to this type of political agreement. Whereas treaties are difficult to change.”

American Matthew Desch is CEO of Iridium Communications, a company building the Iridium NEXT constellation of 66 satellites in low Earth orbit. In 2009, one of the company’s satellites was struck by a Russian satellite in the first reported incident of a functioning satellite destroyed by an accidental collision:

“Given our experience in this area, we are very supportive of this U.N. working group effort. This is a reasonable first step, but frankly, much more needs to be done and it lacks ‘teeth,’ as it all depends on the good will of all parties — many who may not have the incentives to comply. Still, we’re encouraged by the work and are hopeful this will help provide a baseline for future operators and constellations. Iridium is already following these guidelines.”